“I’m not so worried about an ending,” says comedian Radhika Vaz, when asked about how she puts together material for her shows. “I know that technically, as a comedian, you should end on a high note and leave the audience wanting, but I’m like, nah, fuck that. If I give them three or four really hardcore, good laughs in the beginning, they’ll live with how I end.”

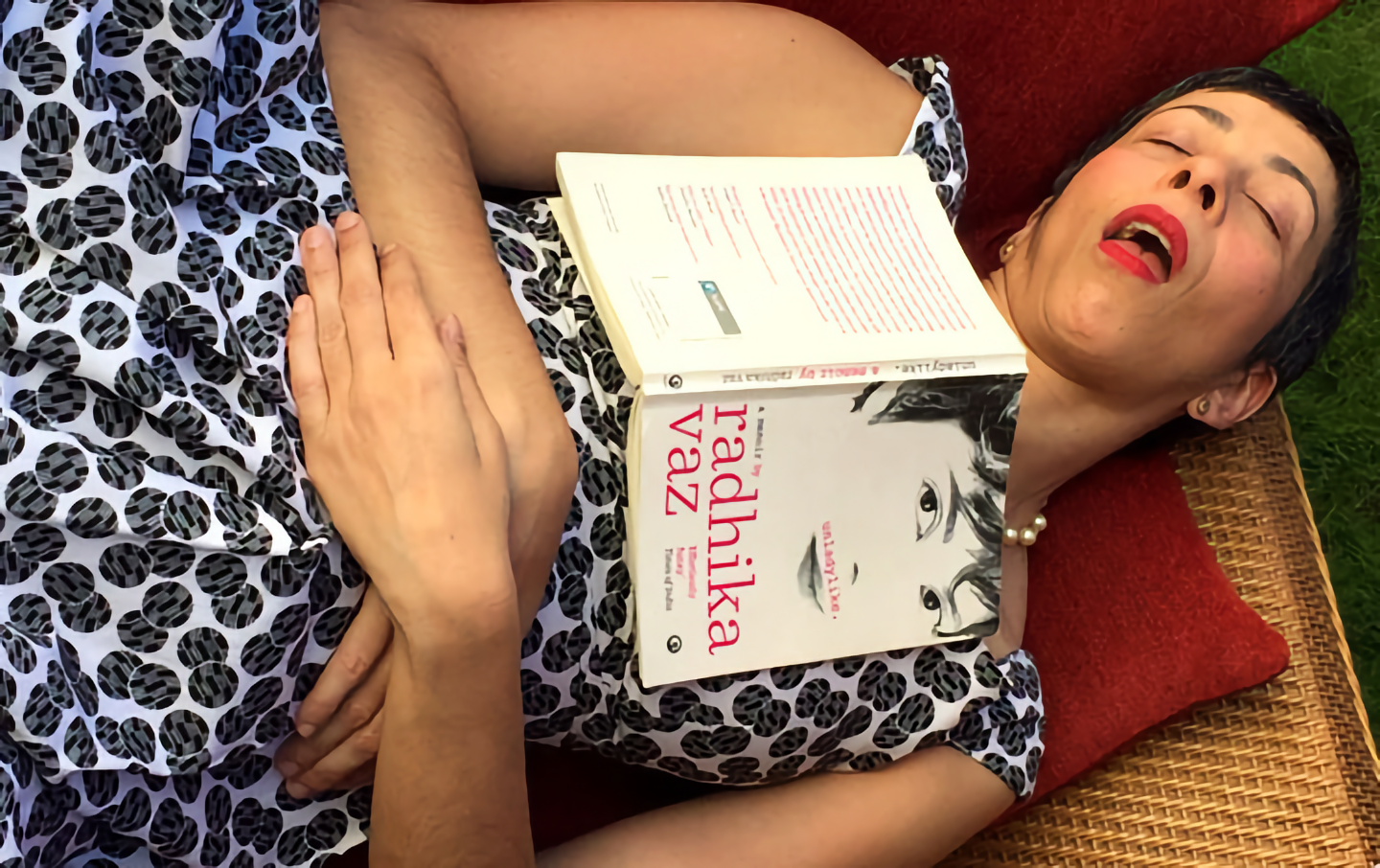

Radhika started her comedy career by teaching improv comedy in New York City, and gradually moved on to performing her own material. Her solo shows Unladylike and Older. Angrier. Hairier. have been well received by audiences and critics across India, and today, she is one of the most well-recognised comedians in the country. She is currently working on her third show and has recently released a book of memoirs, also titled Unladylike (Aleph).

Read on for excerpts from a conversation with her about her largely nomadic existence as a kid, her 25-year school reunion, selling credit cards on the phone, dealing with YouTube commenters, her comedy, and how films are a major part of her plans for the future.

You were born in Bombay, but you’ve moved around a fair bit. What were your early years like, considering you’ve lived in so many places and attended so many different schools? Was it disorienting for you, or did you just accept it as the way things were?

I mean, at that age, nothing is disorienting, because it’s what you’re used to, you know? I was just used to growing up with my parents living out of boxes all the time. When I was even younger, my dad’s postings would change every nine months. Sometimes, we’d just sort of move in and barely unpack before we had to move out again. It was very normal for me. I don’t think it was disorienting or in any way a bad thing, when I was very young. In fact, when I look back on it, I really appreciate the upbringing that I had, because it did make me less rigid about a lot of things. Where you live, how you live, do you have your own room, your own things—I mean, we didn’t have any of that.

The other thing about growing up in the Air Force is that you don’t grow up with the same group of people; they keep changing. It’s also not a homogenous group: it’s everybody from everywhere, a real cross-section of India. I feel lucky to have grown up with those influences. For me, family isn’t a bunch of people with my exact D.N.A. For me, family is my dad’s close friends and their wives, and my mum’s friends. I think it’s a privilege to have a wide group of people to help raise you. You don’t have a lot of prejudices, you don’t grow up with any of that shit. I never grew up looking at people like, what’s their last name, where they’re from, their religion, if they looked like me, none of that.

As I got older—nine, ten, eleven—that’s when you start to, as a kid… well, I don’t know about other kids, but my parents felt that maybe at that age, I needed a little more stability. That’s when I went to boarding school. I was still going home during my holidays to all these places that my dad was posted in, but at least boarding school gave me the chance to go back to the same school every year.

And the same people.

And the same people, yeah. Again, boarding school being boarding school, you get people from everywhere, so in a sense that was still nice. I think my parents had the right idea. Maybe it would have been disorienting after a certain age to be moving around every year.

Being an only child, did you find it hard to keep yourself entertained when you were growing up?

No, no, no, no, not at all. I think moving around made me the kind of person who makes friends very easily. At the very least, I was never very shy about making friends. I was never really bored, and I’ve always had an active imagination (laughs). There was a lot of talking to myself and creating plays for myself if nobody else wanted to watch, just sort of fooling around. I’m pretty good at wasting time on my own.

Do you still remember any of those plays?

Oh my god, there’s a photograph, actually. Do I have the photograph? I used to take all my stuffed toys and I would make them my cast members. Then the play would just go in any direction. I wasn’t a puppeteer, but it was sort of like, ‘oh, Monkey and Cat are going to go for a walk’. I think my parents thought it was the worst shit that they’d seen in their lives (laughs).

(Laughs)

But I was an only child and I was a kid, so they were like, that’s lovely (laughs). Even now, I’m quite happy hanging out on my own, watching random stuff on YouTube, reading, watching T.V. Yeah.

Did you read a lot as a kid?

Not as much as I do now. Both my parents are readers and my mum especially tried to inculcate the habit in me. I remember I went through phases as a kid: I would read a whole lot of stuff one year and not really be engaged with books for a while after that, and so on. I’ve always been more influenced by my peers than my parents. If I hung around with a crowd that did a lot of reading of specific kinds of books, I would read those, and if I hung out with a bunch of losers who didn’t read at all, then I would be one of them, happily.

Was reading a way for you to be a part of the conversation?

It was just because that’s what my friends were doing, you know? It wasn’t even a conscious thing, almost. In fact, my dad always says that I sound exactly like the person I’ve been hanging out with. He said that he could always tell who I’d been with when I walked in the door, because I’d spend the next 20 minutes sounding exactly like that person. It was nothing deeper than, oh, my friends are wearing black, I’m going to wear black. My friends are reading, so I’ll read as well.

Did you like going to boarding school?

I didn’t when I first went, you know, I was homesick. But then I loved it. I loved it. It becomes home after a point.

In Unladylike, you’ve written that you had a very unrealistic notion of what boarding school would be like based on Mallory Towers.

Yes, from Mallory Towers and also because my mum went to boarding school. I’d been given a rather positive view of the whole thing. Needless to say, boarding school is not exactly Mallory Towers.

(Laughs)

Ours certainly was not. It was still a lot of fun. Actually, we just did our 25-year reunion for our batch. It was quite intense for me, and for many other people, I’m sure. I didn’t leave school on the highest note. I was sort of asked to leave school after 10th grade, and I didn’t get asked back for my 11th grade. At the time it was the most traumatic thing that had happened to me, and I think I carried that baggage for many years. I don’t know how many people you know who went to boarding school, but generally, boarding school people are pretty gung-ho about school and attending the annual school celebration and stuff. I have a lot of friends who do that, but I never went. For the 25th year reunion, there were a handful of my close friends from school who were going, and they were very keen for me to attend the event. I didn’t really want to go, but I went and ended up having a really good time. And it made me remember how close we all were. We were little kids, all living together, you know? There was a certain point where we were just trained to love our parents more, you know what I’m saying? But we didn’t really. I think we really loved each other a lot, and it became apparent to me that I was distraught when I left school because they were my family at that point.

Was there anyone at the reunion that you didn’t recognise after all this time?

Oh, lots of people. Not like half the class, or whatever, but there were five or six people that I solidly could not recognise. And it was completely on them, because nobody else recognised them either (laughs).

(Laughs)

The women, of course, I recognised. Maybe that’s just because there were fewer of us in the batch, and even fewer who were actually at the reunion.

“I’m pretty good at wasting time on my own.”

Were you studious in school?

No, I hated studying. And it showed (laughs). The results were just abysmal. I don’t know if it was because I was bored, but I just didn’t engage. I didn’t know how to study; I didn’t even know what that meant. And in my school, even though the classes were small, there wasn’t a lot of attention given to the kids who were weak. The kids who were strong got stronger. Really, at the end of the day, I wonder how much more I would have enjoyed school if I were more engaged. I think I would have. I always think that it’s sad that I didn’t engage more with my academics, in school and in college. In fact, I have to say I was even less engaged in college. I think I only became engaged in everything once I started working. Then learning things about the trade or paying attention to stuff started to matter.

Did you participate in a lot of extracurricular activities in school?

Absolutely. Every extracurricular activity that I could be involved in, I was. Drama, debates, poetry recitation, any old shit. Anything that didn’t involve speed and hand-eye coordination (laughs). I wasn’t very good at all at athletics. But I was a team player, so I was in the hockey team. I think they were short of players.

(Laughs)

My dad always used to say, ‘How is it that she can’t remember anything that’s taught in class, but she can learn lines for a play? What’s the difference?’ And I’d be like, I don’t know what the difference is!

Yeah, it's like people having no trouble recalling random song lyrics from 10, 15 years ago.

Exactly, right? It’s the same thing! (Laughs) I was in Bangalore for New Year’s, and a few days before that I’d gone to this place with my friends. We’d been told that they play amazing retro music. I was thinking retro like ‘70s, but the DJ was hitting, like, late ‘80s, early ‘90s. But it was bizarre, we knew all the words. I’d forgotten about the songs, even, but I still knew all the words.

What sort of characters did you like to play in your school plays?

I would have played anything. School plays, man, they were what they were. This is how it was: we had prep school, junior school, senior school, and the 12th standard. Each division had their own play. It was one play, and it was whatever the teacher who was in charge had picked. The kids who were interested would be put in the play. There weren’t too many kids who were interested in drama. There was a small group of us who were pretty much in all the plays all through school. The roles didn’t matter. They were dramatic plays, but I think they may have looked like comedies to the audience (laughs). They were so poorly done (laughs). But it meant a lot to us at the time. I don’t think I learnt a lot about drama and theatre in school, except that diction was very important.

Were you into music?

I’m kind of into music the way… you know how some people call themselves foodies, but they don’t know shit about food? They just like to eat. That’s the level of how much into music I am.

(Laughs)

I love to listen to music, to dance. I didn’t learn piano or join a band in school, though many of my friends did. I enjoy music, but I don’t have a musical bent.

Where did you study after your 10th standard?

I went to Mount Carmel College in Bangalore, where I completed my 11th and 12th.

Wait, why were you asked to leave school after your 10th?

Because our headmaster’s a weirdo. That was one of the things we all talked about at our 25-year reunion. I realised that I wasn’t the only one who had been treated in an unjust fashion. I was just sort of a naughty kid, but I wasn’t bad. What happened was that my very best friend got caught smoking, and when they caught her smoking, they asked some of us about it. I obviously said that I didn’t know anything about it, but they knew that I was one of the few people who knew for sure, and even went with her when she smoked, though I never smoked myself. Then I got caught for lying about it, etc. You know, when you look back at what really happened… I mean, the letter that my parents received said that I was very poor at academics, I was a troublemaker, I had a boyfriend, and none of these things were really… I mean, you had to kick a kid out of school for this shit? I mean, whatever, dude.

Did you attend a college in Bangalore as well?

No, I came to Bombay. My dad’s family is from Bombay, and I was used to the city, because I used to visit every other year during my holidays. My mum went to college in Delhi, but for whatever reason, my parents didn’t want me to go to college there. I think I’d have been happy going to college anywhere. But I’m glad I went to Bombay.

What college were you in?

Sophia College for Women.

(Laughs)

Sophia College was interesting, because we were all at that age where we were horny 17-, 18-, 19-year-old girls, but we were sort of being guarded by the nuns.

(Laughs)

I think it was just a weird… you know, college is for experimenting and making bad decisions, really. But we were being watched in a way that ensured the complete opposite. It was a bizarre experience for me. But I’m glad it was in Bombay. I made a few friends. I think I grew up a little bit. Living in such a large, sprawling city on your own for the first time makes you a little more independent—you use public transport, you’re not fussed over by your parents, stuff like that. Again, I wish I had engaged more with college and with Bombay. Yeah. So many regrets (laughs).

Were there any people that you came across in school and college that you looked up to? Maybe teachers or other mentors?

More than my teachers, my parents had a couple of close family friends who, over the years, I did look up to. At least I thought they were cool examples of people who were different from me. My husband has a very close friend whose ex-wife I met when I was about 25. She was 32 at the time, and worked for the United Nations in Delhi. She’s a Swedish woman. I remember, that was the first time I wanted to be exactly like someone else. I wanted to be exactly like her the moment I was her age. Living on my own, working a good job, not married, living with some guy who’s seven years younger than me. Maybe not exactly like that, but I look at people and their lifestyles, and think that I’d like to be like them. Oddly enough, nobody in comedy or acting has affected me like that.

You mentioned earlier as well that your father can tell who you’ve been around just from the way you act. Have you ever thought about why you like to look at how other people live and what makes you want to be like them?

I think it’s just a lack of security. I mean, comedians and performers are known for insecurity issues. I won’t pretend I don’t have any. I think I’ve always been more fascinated by other people’s lives, and hence, observing them today is not a problem. I think my comedy so far has been more about observing my own psychology and my own responses to things, but they’re definitely also in context to how other people are around me. I’m always asking people a lot of questions: where are you from, what language do you speak, everything. Maybe it was moving around that made me like this. I’d be the new kid in town every year, and I’d have to find out shit about other people if I wanted to be their friend. And also… I’m wondering about this, now that you’ve brought it up: being an only kid—do you have siblings?

Yeah.

When you have siblings, and you’re in a family, you think that there are two or three of us who are kind of the same. But when you’re an only kid in a family of three, you sometimes think that you’re the only one feeling all of this stuff, and it can be weird. I don’t know if that’s played some kind of role in it.

“Initially, I had these fantasies about what my life would be like, and I realised very quickly that no matter where in the world you live, you have to make the fantasy come true.”

I remember that I used to try to emulate other people’s handwriting in school, people that I used to like.

Oh, God! I keep trying to do that too! I have two friends, they’re twins. They have the loveliest handwriting, and I would keep trying to copy it. You’re absolutely right. There are all these little things that you suddenly start thinking about. Dressing styles? My god, my friend Anuli who lives in Bombay? I was the biggest fucking copycat, man. I’m surprised I didn’t try to steal any of her stuff.

(Laughs)

At one point, when I was living in New York, I was unable to remember what I sounded like. I didn’t have an American accent, by any stretch, but I had a strange-sounding accent that I had come up with (laughs). I feel like it’s only now, finally, that I’m able to say that this is what I sound like and this is the stuff I find funny. But I’m forty-fucking-three, man. Thank God.

What was your first job?

My very first job was in tele-sales, in Bangalore. It was selling Standard Chartered credit cards on the phone. But we weren’t even in sales, it was more like a receiving unit? Credit cards were kind of rare back then—this was about 23 years ago. I had that job for almost a year.

Did you like the job?

I didn’t mind it.

Can you recall any weird calls that you received at the time?

Every now and then, we would get a guy or a woman—but mainly men—who’d be like, ‘Oh, what’s your name? Where do you live? Are you from Bangalore?’ But we were young at the time and found it funny, or whatever. There was some of that, and sometimes, we’d call people and they’d just be lonely. We’d talk to them and they’d be so happy to talk to us, and you know, we’d realise later that we were the first people they’d spoken to in days. I think I’ve only disliked one job, and it was my first job in America. And it wasn’t so much the job as the circumstances around it. I was in America when 9/11 happened; I was in New York. It was just a bad time—people were being fired, there was a lot of tension, and I didn’t end up making a lot of friends. Even in the company I joined, we were a small team, someone had just been fired before I joined, there was all of that. But yeah, that was the only job I had that I was unhappy with.

That was about 15 years ago?

Yeah. It was amazing, obviously. New York is a very overwhelming city. Initially, I had these fantasies about what my life would be like, and I realised very quickly that no matter where in the world you live, you have to make the fantasy come true. And that’s how I got into comedy. I’d wake up in the morning, go to the gym, go to work, and that was it. By about eight at night I was done with everything, if not earlier, and then I’d just sit and watch T.V., and on the weekends I’d get wasted—which was great for a while. But after a while I started to get depressed, because in Bangalore I was doing stuff with all my friends, but in New York, I didn’t really have that many friends. That’s when it was suggested to me that I start taking a class of some sort, and I sort of fell into improv and then from there, comedy.

Farting, blowjobs, nagging: the outrageously funny Radhika Vaz talks about how she began writing her first solo show, Unladylike.

Did you always have an interest in comedy?

My dad was a very big vocal comedy fan, and he introduced me to a lot of comedy through records and movies and stuff, but I had no real interest in pursuing it myself. When I started taking classes, my interest was acting, because that was something that I remembered doing in school, and I was more and more fascinated by the process as I got older. That was the intention. I ended up taking a free improv class, because that was happening the day I went to pick up the prospectus. I loved the teacher. She would have been one of those people I looked up to—it was instant. For the first few years, it was really more about socialising than anything else, to get to know the city and the people in it in a more intimate way than just going to work and coming back.

At what point did you start taking comedy seriously?

I think I started looking at it as an optional career when I started teaching improv. I took about two or three years of classes before I started teaching a very basic level of improv. That was when I thought to myself that even if I didn’t became a famous actor, I could teach and still be within the ‘world’. For me, the ‘world’ has always been more important than anything else. Everything else is important because you need a certain amount of money to survive, and you need a certain amount of fame to get that money, because people are assholes and they only think that famous people do worthwhile things—you know, it’s such a stupid psychology. All that matters, but for me, the ‘world’ and the people who inhabit it were, and still are, more interesting. Until then, I didn’t think I could do anything other than a regular job. It was only once I started teaching improv and had some level of success with it that I started to think that this could be a possibility, and I started writing monologues and things like that.

Radhika Vaz performing Unladylike at Michigan State University.

Did you begin by participating in open mics and other similar events?

I didn’t. My entry point was different; I came in through improv. Every fucking improv show is almost like an open mic, because none of it is ever practised, and I did a lot of that. At one point I did improv shows twice a week, for a long time, and I gained a lot of experience with that. When I started doing open mics, it was interesting. It was when I wrote my first one-woman show—I was very, very nervous, because I had never been alone on stage up until then. A friend of mine recommended that I go to open mics. She told me to cut up my hour-long monologue into five-minute bits and perform them on stage; to get it out of my system so I wouldn’t be nervous anymore. The first open mic I signed up for, I didn’t go. The second time, my friend came with me. The third one I went to was the first one I went for alone, and I forgot everything. I was standing on stage, and was like, fuck, I’ve forgotten my lines (laughs). I had nothing to say. But that got me over my fear. It was the worst thing that could have happened: I forgot all my material. And nothing bad happened. After that I did open mics only to learn my lines. I do them in India, though, but it’s mainly a way to meet the other comedians in the scene.

When did you perform your first solo show?

In 2010, on the 10th of September.

How long did you take to put the show together?

It was a little more than nine months in the making. A lot of the stories got written very quickly, some of them took longer, and then I had to learn the lines. For me, the line-learning was very daunting. Now I wouldn’t give myself quite as much time to learn the lines as I did back then. The show was Unladylike, which is also the name of my book.

What sort of venue was it?

It was a tiny venue, a 70-80 seater. They call them ‘black box’ venues. The whole place is painted black. You don’t have curtains, you have a small lights and sound setup. My first show was done in collaboration with my friend Brock, Brock Savage.

That’s such a cool name.

Yeah, it’s a great name. It’s one of the coolest fucking names ever. He’s a director and a very well-trained actor, and the funniest guy. I wrote the show, but he directed me a lot. We just hit it off, we found each other very entertaining. And I think that’s important, when you’re creating stuff together. For my second show, I didn’t use a director, but for my first show, I think I wanted as many people around me as possible. I was a little frightened and not very confident. It all comes down to confidence, man.

Tell me about your second show, Older. Angrier. Hairier.

My second show was written under very different circumstances. I had joined a writing group and we were all going to write about feminist issues. The reason we did it was because all of us wanted to read more, and we knew that if we joined a group where we had to read and write essays about what we’d been reading, we would at least read with mindfulness. A lot of the material for my second show came from that, because I was very specifically looking at ageing, children, and domestic issues, the control that women like to have in the house. About how we are the ones who are always keeping things clean, etc. I just kept writing essays about shit that was bothering me, or just about issues that women face. You know, there are so many day-to-day, little things that we do that sort of hold us back. I wrote all of this stuff in a comedic format, and also related it back to my own experiences. That’s how Older. Angrier. came about.

Do you think that theatricality is important for a stand-up performance?

It’s so subjective, Arun. Some people are very physical. I’m a big fan of, like, physical, slapstick-y comedy. I mean, I expect the person to be smart and funny and make a point, but I love seeing someone who’s physical. There’s a movie I always talk about, called 9 to 5. It has Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton, and it is hilarious. It’s kind of like an action-comedy film: their boss is an asshole, and they take him hostage, and they spend the rest of the film trying to hide the fact that they’ve taken him somewhere. All three actresses are so physical in their comedy. To me that’s the holy grail.

When I’m on stage, I love doing characters, I like expressing my mood using my face and my body. I really enjoy it. There are definitely a lot of comedians who don’t do any of that—they’re totally deadpan, but even they are fun to watch. I know that I can pull off physical humour, just like I know that there are some things I can’t pull off, like maybe Hinglish jokes. I don’t have the reference or the context around a lot of, like, when people make jokes about Sindhis or Gujjus or Christians in India. You know, I get it, but it doesn’t come to me naturally. The physical stuff comes to me naturally and I like to use it as much as possible.

Shugs & Fats is a Gotham Award-winning webseries by Radhika Vaz and Nadia Manzoor.

How important is editing when it comes to creating material for a stand-up performance?

I think it definitely has its place, but it is a double-edged sword. If you edit too early, then you sometimes throw out the baby with the bathwater, so to speak. Editing is important, but you definitely don’t want to cut something out that could work.

Besides stand-up comedy, you’ve also done web-based shows like Shugs & Fats with Nadia Manzoor, and collaborations with other Indian comedians, like Abish Mathew. How big of a role do you think the Internet now plays for comedians? Do you see the digital medium affecting your live performances as well?

Yeah. Anyone who thinks that the Internet doesn’t affect anything these days is crazy. The impact of social media—and when I say social media, I’m including YouTube as well—is huge. The fact of the matter is that if you have a very large social media following that has built up organically, it’s a great marketing tool. That’s one part of it. The other part of it is reach. There are people who may never come to see one of my shows, but I can give them a taste of my comedy through mediums like YouTube, and that goes even for my book. That’s why I was keen to do the web series with Nadia. First of all, we were doing it with these two characters that I love. It was just an opportunity for me to do a different kind of comedy, for a different kind of audience to see it, including people who haven’t seen me live. I definitely think the Internet plays a huge role and it’s only going to get bigger. A lot of people ask me what the next thing for me is, and it’s video. Writing for, directing, acting in. I don’t care if it’s for a film, a television series, a web series, or just a one-off video. It’s just the medium that I’m interested in. The landscape has just changed so drastically for storytellers. I think that’s awesome.

How do you deal with commenters on YouTube? Or do you not bother reading comments on your videos?

I did read them, at one point. When I did my first terrorist wife video, that one got such a lot of action, because, you know, I called it terrorist wife. I don’t really do things with the intention of ruffling feathers. I never do anything thinking, I’m going to fuck around with this group of people. It’s never that. It’s just, this needs to come out, somehow. But some of the comments for that video were like, ‘She’s so fucking ugly’. I was like, really? (Laughs) ’She’s not even funny, my mom’s funnier,’ to which another guy replied, ‘So put her on.’ (Laughs)

(Laughs)

Now, I don’t really read a lot of the comments at all. I do read the messages that come to me on Twitter, but I don’t have a huge Twitter follower base. I get messages on Instagram as well, which seems to be a little more polite. The only thing that would bother me is that if other people started fights with each other because of what I said. But if it’s directly with me, I don’t give a fuck. You can’t be too thin-skinned in this job, man. You won’t last long.

Radhika Vaz talks to Astray about how she started writing her recently released book Unladylike.

Yeah. But I’m sure it does get to everyone a little bit. People on the Internet say whatever they want, without thinking about the consequences.

Whatever they want, yeah. I think as a woman, I have to admit that when my looks are called into question, it is fucking shocking. As a rule in society, we’re quite polite about how we are (laughs). See, like, guys, when you all are growing up, you’re like, eh, you’re ugly, you’re fat, you’re short, you’re thin, you’re dark. Boys are hardy. They’re used to it. But no one ever said it to me, because I’m a girl. And I feel like we should stop doing that. Everyone should say shit to everyone else from a young age, so that when you’re grown up, you don’t care about any of it. In general, women are a little softer, and a little more… you know, I’m a big proponent of thinking that your looks are not very important, because it’s true, they aren’t. But even then, if I’m honest, the moment I see a ‘you’re so ugly’ comment, I’m like ‘aaah’. These days, though, I’m used to all of this rubbish so I don’t care.

Coming to your book: was it hard to write? You’ve mentioned in the book that a lot of the stuff that you’ve written about isn’t something you’re proud of now.

Almost all of it (laughs).

You’ve written that some of it is also at odds with your feminist beliefs. Was it hard to include those sections of writing in the book?

No, it wasn’t hard putting them into the book, it’s very hard looking at it now (laughs). I remember when I read the book for the first time, I called my editor and said, my god, some of this is unbearable! She said, ‘It’s fine.’ What she didn’t say was, ‘It’s too late!’

(Laughs)

The funny thing is that in my shows, I talk about such personal, intimate shit, and it’s getting more and more so as the years go by. I feel like I say these things [during my performances] and they go off into the air, and that’s it. But with a book, I feel like it’s there, and people can turn to any page and see what I’ve written. That made me a little nervous for a minute, and then I was like, what’s wrong with me? It’s the same thing. I just let it go. And now that I’ve done it once it just feels like, just, whatever.

“A lot of people ask me what the next thing for me is, and it’s video. Writing for, directing, acting in.”

If someone came to you for advice on how to become a professional stand-up comedian, what is the one thing you would tell them not to do?

That’s a very good question (laughs). What’s the one thing I would tell you not to do? Do not… I mean, don’t give up. Don’t give up. I mean, have a job if you have to. The thing with stand-up comedy, or starting your own website, or doing anything on your own that’s kind of solitary in a way, and where the rewards may not be public for a very long time—or even private, for that matter—I think it’s important to not give up. It’s just a question of really believing that you can do it, or really loving it. I think there are two kinds of people who do the kind of stuff that all of us do. The people who love it and feel passion, they’ll never give it up. They’ll find a way to continue to be a part of that life. It’s about the life, I think. The people they meet, the experiences they have. So many of them have jobs; most of my comedian friends in the States have jobs that have nothing to do with the art world. And then you have the people who are passionate about it but they really want to make it their job. And then you have even less reason to give up. Why do we give up? It’s mostly for stupid reasons, because of our ego. It’s just ego, no? If I’m not fucking number one, then fuck it, I’m not going to do this shit. How do you become number one? Do you think number one just became number one? Not everyone’s J. Law.

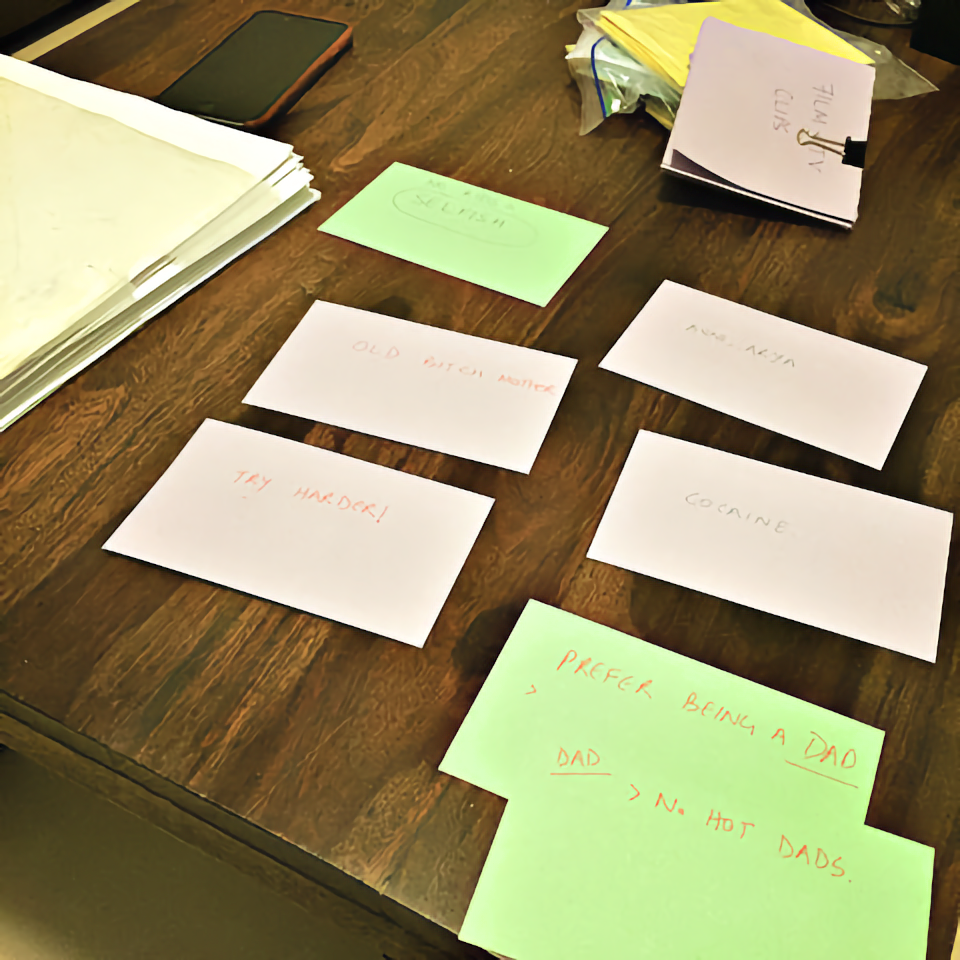

The Setup / Radhika Vaz

"I use some pretty hi-technology stuff to create the magic. First up—a pen. Have you ever seen one? NO? Well, you can WRITE with it. I also have paper. AND flash cards. I use the pen and paper to write down every thought pertaining to a particular subject. The flash cards are to help me create the ideal flow once the material is written. This is a trademarked process. No one had better try and copy it."