"Music shapes the way I look at things," says Priyesh Trivedi, a 23-year-old visual artist from Mumbai, who has been making waves with his immensely popular Adarsh Balak series of paintings. "If I listen to minimal stuff, I start to perceive and draw things in a minimal way. If I listen to avant-garde, I start looking for the unusual in everything, and that causes another shift in my art. I don't think too much about it, I just like to go with the flow."

Priyesh is an accomplished illustrator and a trained animation filmmaker, and currently resides in Borivali, Mumbai. Read on for excerpts from a conversation with him about his development as an artist, the state of the animation industry in India, the process behind his Adarsh Balak series of paintings, and dealing with fame on the Internet.

Have you ever offered a joint to your father?

(Laughs) No, not really. But we do talk about it. We have very open conversations about [smoking pot]. There's no negativity attached to it in my house, but I haven't quite got to the point where I can freely offer a joint to my father. But one day I hope to, yeah (smiles).

Are your parents cool with the idea of smoking weed?

Not really. They are well aware of the medical implications of smoking cannabis because I explained things to them, but they wouldn't really be cool with me smoking up (smiles).

Did you grow up in Bombay?

I was born in Borivali, but we shifted our residence a few times — once to Nalasopara, twice within Dahisar, and then back to Borivali, all before I was 16. I've been living in my current house for the past seven or eight years. But yes, I've been born and brought up in Bombay.

Do you like living in Borivali?

Where I live doesn't really matter to me. Once I get inside my room, it doesn't matter if it's in Borivali or New Delhi. When I start working, the world sort of narrows down for me. It shrinks to where I am, to a radius of about three to four feet around me. I just focus on what I'm doing. Wherever I live, as long as I can recreate the atmosphere that exists in my room, it doesn't matter if I am in Borivali or on Mars or wherever (chuckles).

Did you go to school in Borivali as well?

Yeah, I went to St. Xavier's School—but the suburban St. Xavier's school, the one in Borivali, not the one in town (laughs).

(Laughs) Did you like going to school?

No. I was a loner in school. I did have friends, but very few. Even now, I'm not too big on socialising. I think it was good in a way. I got a lot of time to myself, to think, to draw, to doodle, instead of just fooling around like the other kids. I went to school only because if I didn't, I would be screwed. I didn't really want to study, and even now, I don't really feel like studying [further]. It was just something I had to do, so I did it.

Have you been drawing from a very early age?

Yeah. Ever since I can remember.

What kind of stuff did you like drawing as a kid?

I was really into nature. I used to draw and paint a lot of landscapes and birds, after which I got into human anatomy. I didn't really like anatomy as a kid, but you have to learn to draw human figures properly if you want to appear for Elementary and Intermediate grade exams.

Did you ever take lessons?

I did undergo some training for those exams, but I didn't really focus on the required subjects during the training sessions. Instead I chose to draw birds and flowers, which kinda pissed my mentor off.

(Laughs)

Yeah. She used to complain to my parents about how I didn't like to draw human figures. I was really into parrots at the time. I still love parrots, and love to paint them even now.

What is it about parrots that you like?

Not just parrots—I love birds in general, because of their colours, and the patterns and textures that they have. Painting birds can teach you a lot about colour theory, and can improve your control over your paintbrush. Not just birds, but nature in general. The best way to improve is just to observe, draw, and paint nature.

Did you move on to exploring other themes and subjects as well?

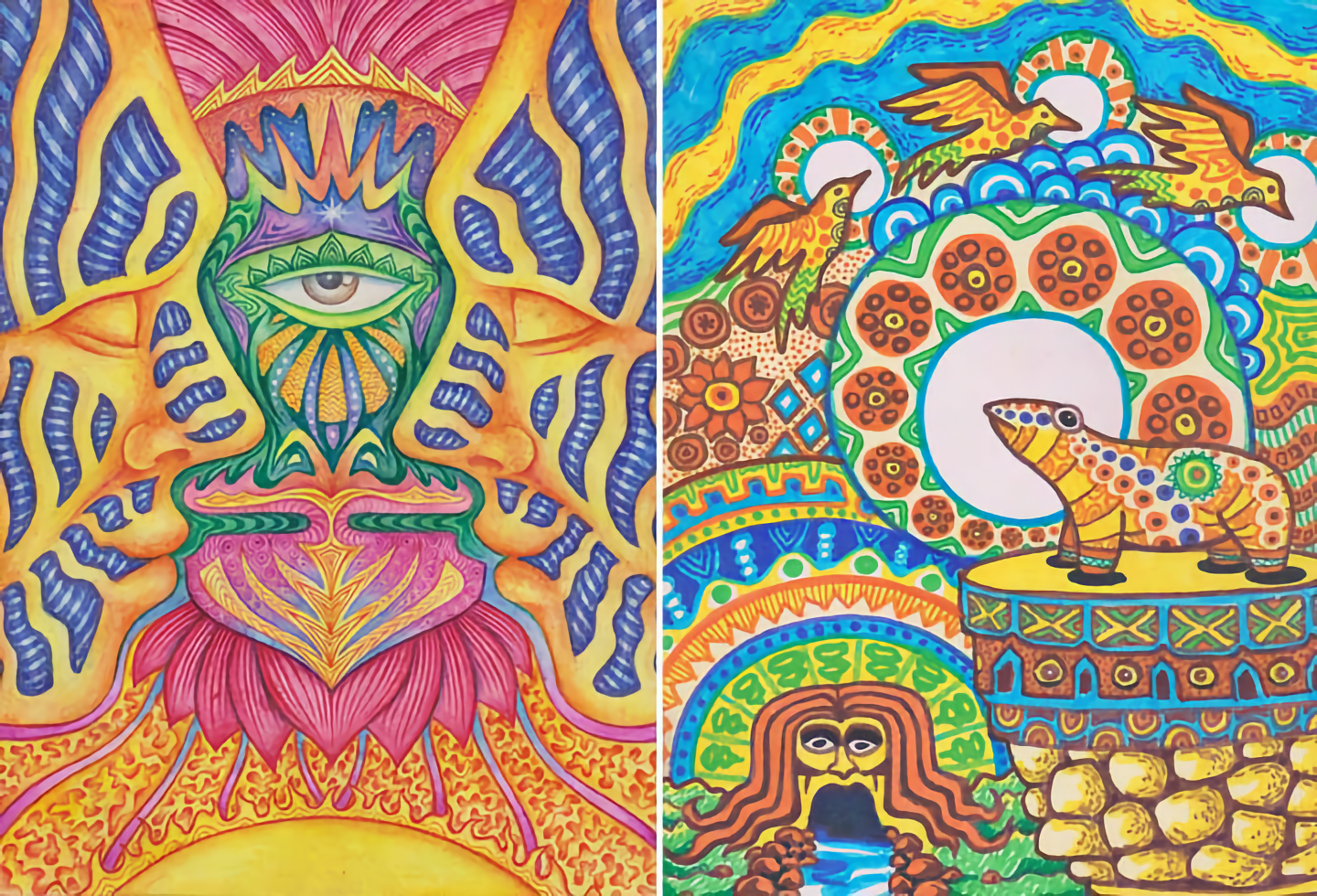

I think I was 16 or 17 when I started to explore and discover new styles and art movements. That was when I started to learn about art history (in my own capacity) and got more exposure to global art. The style which I could relate to the most was surrealism and psychedelic art. Up until two years ago, I was really big on psychedelic art. That style of art was very intuitive for me. I didn't have to try, it just flowed from my head onto the canvas. But as an artist, I think it's very important not to settle on just one thing. Keep experimenting and see what works for you. I'm very afraid of belonging to any one niche. I dabbled with realism, I dabbled with abstract art, I dabbled with psychedelic art. I've even tried my hand at sculpting. That didn't really work out well, so I didn't carry on with it, but I would like to return to it at some point. These days I'm more into surrealism and minimalism.

Do you feel that appearing for the Elementary and Intermediate art exams helped you in any way?

No, not really. But I wanted to apply for a commercial art course, and back then you needed an Intermediate exam certificate to be able to apply to an art school. I gave both exams, but though I got my result for the Intermediate exam, I didn't receive a certificate. I tried asking the school authorities and even the board that organises the examinations for my certificate, but to no avail. As a result, I couldn't apply for a B.F.A., which is why I was pretty directionless until my 12th.

“As an artist, I think it’s very important not to settle on just one thing. Keep experimenting and see what works for you.”

Which college did you go to?

Thakur College in Kandivali. The whole Intermediate exam incident made me give up the idea of pursuing a commercial art career, and I took up commerce. I was almost set to do some finance-related course and take up art just as a hobby. But after my 12th, I came across a B.Sc. course in animation filmmaking at Thakur College itself, which I decided to pursue. It's a course where they train you in 2-D and 3-D animation, and you're supposed to make a film as your final year project. It's a very intensive course. After doing that for three years, the fact that I couldn't get into art school didn't really bother me, because I felt that this was better.

Did you work at an animation studio after your course?

I was always into animation and films, but in India, the animation industry sort of functions as a slave ship. I saw that, and I realised that it wasn't what I wanted. After I completed my course, I started working as a game artist at a studio called Mile Nine in Andheri. When I was studying animation, I used to work as a concept artist—that was my specialisation. You design characters and layouts, and you basically plan things out. This is something that is common to games, ads, films, etc., which is why I was able to switch from animated films to games very easily.

For how long were you at Mile Nine?

I worked there for a year. I had two reasons for quitting: the first was that I was bored, and secondly, I didn't get the raise that I wanted. I took a break, and when I came back to Bombay...

Did you go out of town for a while?

Yeah, whenever I quit a job, I like to travel. That's like a reset button for me. I went to the hills (north India) after I quit Mile Nine.

What were your subsequent jobs like?

I started working at this place called Maya Digital Studios in Goregaon. That was an eye-opener for me. I learnt how things really function in the animation industry in India.

“When you have non-artists at the top who don't understand the creative process, then it's a problem.”

What made you decide to join an animation studio?

At that point, everyone who saw my character designs said that I should work at an animation studio, because they felt that my style was more suited to animated films than games. I thought I might as well give it a shot. I was at Maya for just two months, but those two months were more than enough for me to realise that okay, at least in this country, I'm not going to work in animation again.

What was it about working there that turned you off? Was there too much mindless work?

Mindless work, yeah, and the money. Even if I was getting paid peanuts I would not have complained. But they don't even give you peanuts. They just give you the cover, the husk of the peanuts (laughs).

(Laughs)

I've seen a lot of shit over there. I could go on until your dictaphone battery runs out.

Give me a couple of examples of what you think is wrong with the animation industry in India.

It's the guys at the top. They don't understand aesthetics, they don't understand the pipeline, and they're not artists themselves. When you have non-artists at the top who don't understand the process that goes on in here (points to his head), then it's a problem. This applies to any creative industry—if the guy at the top has no artistic inclinations or understanding of the process, then it's a problem for him and the people who work under him. Things are bound to fail. The projects I was working on were pretty good, I guess, but there were a lot of payment issues, and I couldn't work for free.

Yeah, of course.

There were people working at Maya who worked for five or six months without pay, and I couldn't understand that. These were people who had come from other cities to work there, and were living in Bombay on rent. I didn't get how they could manage to work for free for so long.

Why were they doing it?

Their hands were tied, basically. I'll tell you how it works: at many studios, they take a certain amount of money—a pretty big amount, actually—from freshers as a deposit, as safety, to ensure that they don't quit the company. Then they pay the employees from their own deposit, and this goes on for about six months, sometimes for up to a year. The amount of time varies from studio to studio, or I should say from slave ship to slave ship. And if you quit, then you don't get any of the deposit back.

That's nuts.

Yeah. Luckily I didn't have to face that, as I had some work experience before I joined the studio. Another thing is that there are all these animation institutes that are sprouting up on every corner of every road. You have kids that are "passing out" on a monthly basis with "education" and no idea of how the industry works. They are clueless and have absolutely no idea of how to proceed. That is where my degree really helped me. If I had opted for the six-month or eight-month animation courses [at these institutes], I would be in the same position today.

“There are all these animation institutes that are sprouting up on every corner of every road. You have kids that are ‘passing out’ on a monthly basis with ‘education’ and no idea of how the industry works.”

Where did you head to after you quit Maya?

I went to Goa (laughs). I was like, fuck this shit. When I came back I found a decent job at Andheri, in Marol Naka. I have this thing with Saki Naka and Marol Naka; they keep appearing in my life (laughs). It's crazy. This job was at a gaming studio, a start-up called Walnut Labs with just two other guys. I was there for around six months. I quit because I kinda got bored of working on educational games for kids, which was what they specialised in. I started working freelance after that (from December 2013), but now I'm getting bored of that as well (laughs). I'm just really not a day job kind of person.

Do you like to keep trying new things?

It's not that I like to do it, it's more that I have to do it. I tend to get bored of things very quickly. I know it's not good when you're a professional, and I'm trying hard to get past it.

Do you think it's important to stick to one thing for a long time?

I don't think so. Actually, it depends on your circumstances. If you have a great opportunity, go for it, move on from what you're doing at the moment. If it's better than what you're doing now, that is. That's how I roll. It may not work for everyone, and it may not even work for me in the future, but then I don't really think a lot about the future.

Can we talk about your Adarsh Balak project?

Sure.

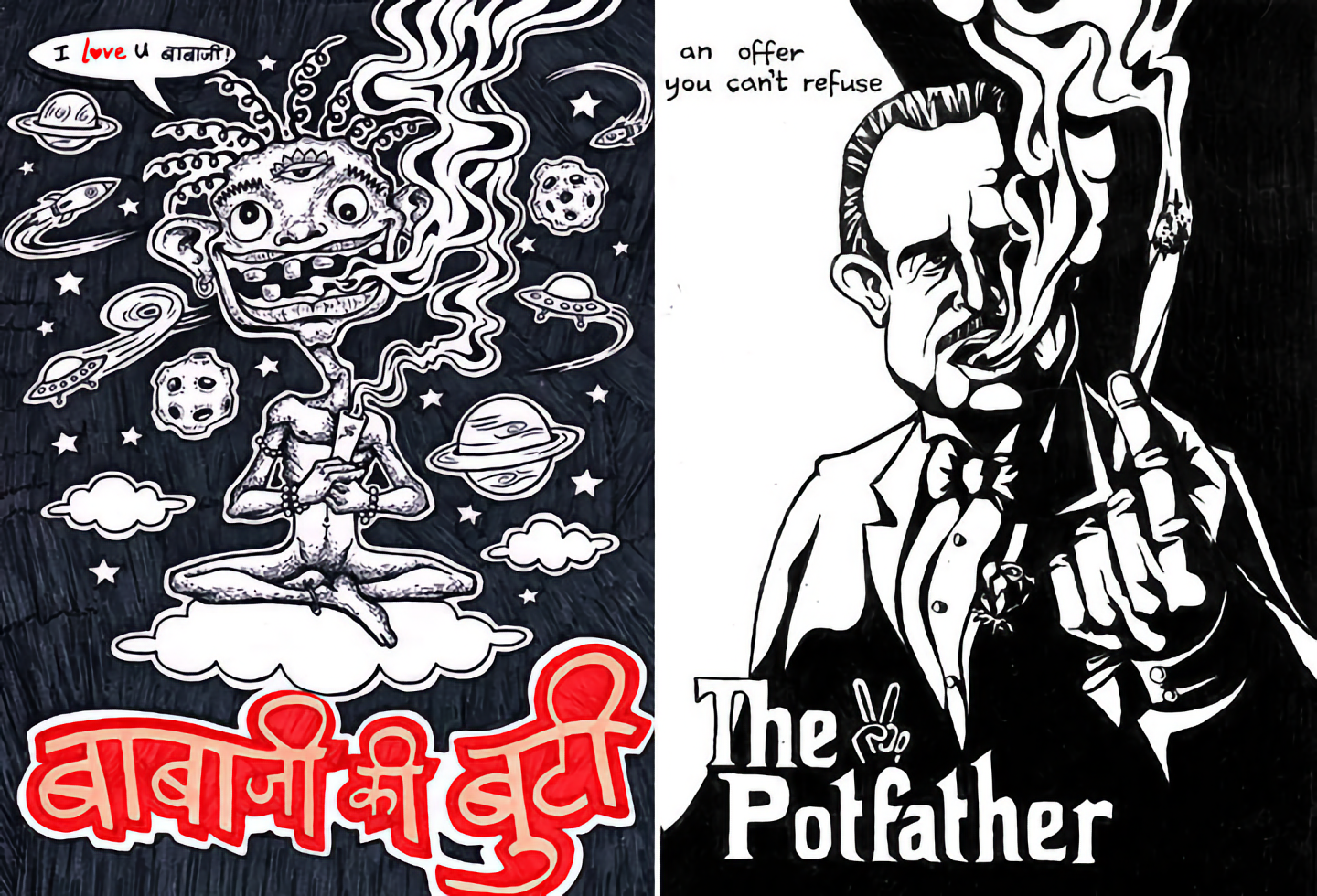

I think the first piece of artwork that you did featuring Adarsh Balak was the 'ट' से 'टोक' ('T' for 'Toke') painting. How did that come about? Did you have a series in mind when you created the first piece?

No. The 'ट' से 'टोक' started as a casual painting. It was just an idea that hit me—I thought it was cool, so I made it. It was actually supposed to be a part of a larger illustration. It was supposed to be that kid and three other friends of his, who are standing with him and waiting for him to finish rolling the joint so they can all get stoned. But after I made the first kid, I thought I should first see what sort of response it gets, how people receive the style. After I painted the kid, I asked myself what more I could do, because I wanted it to be more than just a kid who was rolling a joint. That's when I thought of the Hindi barakhadi charts, with the 'अ' से 'अनार' or whatever, and I came up with 'ट' से 'टोक'. I scanned it and put it up on Facebook and it started to spread. My friends really liked it, and they shared it, and their friends ended up sharing it, and it went on and on. Soon, I started getting messages from people I didn't know, who I have no mutual friends with at all, who started asking me for prints. It was definitely unexpected. I think it was also the first work that I had posted where the number of shares on Facebook exceeded the number of likes.

“My friends really liked it, and they shared it, and their friends ended up sharing it, and it went on and on. Soon, I started getting messages from people I didn't know, who I have no mutual friends with at all, who started asking me for prints.”

Why do you think it became so popular?

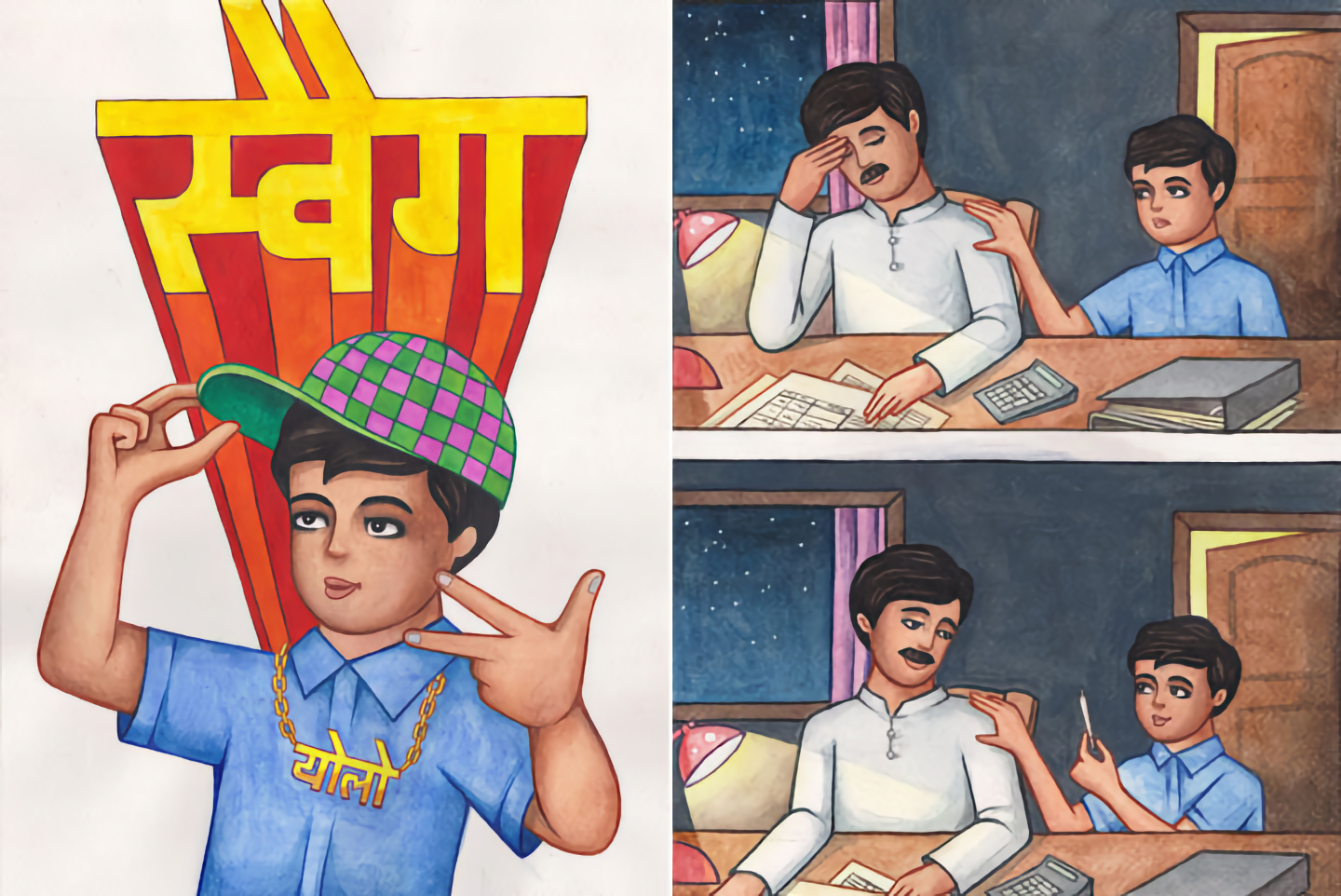

I think it had to do with the nostalgia factor, from the educational posters from the '80s and '90s. I was reconnecting with the style, but there was an entirely different concept behind it. Instead of portraying kids doing good things, I was showing them doing things that I think are good, but that conventional society would not want them to do. They would not want them to go out in the streets and start vandalising or making Molotov Cocktails, or to offer joints to their fathers, or make L.S.D. in their school chemistry labs.

When you got started, did you consciously try to recreate the style of the educational posters? Or did it just happen?

Not really. I still don't know what was going on in my head when I made the 'Toke' illustration. It was a very intuitive thing. I'm really into vintage art and pin-up illustrations and propaganda art. I love the colour palettes, the typography, all of it. I noticed that this style [of the '80s educational posters] was sort of fading away. No one does it anymore. I wanted to reinvent it, but I didn't consciously do it. It just happened.

The other paintings soon followed: the vandal kids, the chemistry student. Your latest Adarsh Balak painting depicts a magic trick, where the boy pulls his own decapitated head out of a hat.

Yeah, instead of a rabbit. Sometimes I just see things in my head—concepts hit me out of nowhere. If I think it's cool I make it. It doesn't necessarily need to have a deeper meaning behind it. I mean, some of them do have a deeper meaning, like the anarchy painting. I feel at some point everyone turns into an anarchist when situations get out of control. It can happen at any level: it can be in your house, in your school, in your city, or your country. When a person feels that he has to revolt, he will revolt. Sometimes it's an individual revolution, sometimes it's collective. The 'Swag' illustration is just something I made because I thought it would look cool. It's not like I wanted it to have any deeper meaning. That one can't be deep even if I wanted it to be.

Have you started working on more Adarsh Balak paintings? What is your process for each one like?

My process is very traditional. All the paintings are done on paper, after which they are scanned. I could have gone digital with the series, but I didn't. I feel that the authenticity would have been compromised. The hard thing about working with cartoon-style paintings is that you have to make sure that the art in each panel is consistent. That takes a lot of time. Standalone illustrations are quicker, but I like to do both. I'm working on new stuff right now, but I don't want to rush anything. I like to take my own time.

“Instead of portraying kids doing good things, I was showing them doing things that I think are good, but that conventional society would not want them to do.”

You recently sold Adarsh Balak prints at a concert in Bombay and employed a pay-what-you-want model of payment. Was that an experiment to see what sort of response you would get?

Actually, I found out about the gig only a couple of days before it was scheduled to happen. The concert organisers got in touch with Visual Disobedience, which is an art collective that I have been a part of, because they'd seen some of my work featured on their website. They didn't know how to reach me, so they tried to do it via Visual Disobedience. They asked me if I wanted to sell prints at the concert. As I said, all this happened just two days before the concert, so I didn't have time to make large prints of my work. I thought of selling postcards with the Adarsh Balak art on them. To make it more interesting, I signed each one of them, and they were all numbered at the back (001, 002, etc.). There was a fishbowl where people could put in their money, and the postcards were laid out on a table. I was there, but I didn't make it obvious that I was the artist. I just wanted to observe and see how people reacted to my art.

What was the response like?

It went pretty well. There were about a hundred signed postcards and all of them got sold.

Are you going to make more prints?

Not for some time now. There are a few things that I still need to figure out. I'm currently talking to a few people about tying up for production and stuff. Prints are not an issue, but I'm focusing more on making t-shirts. My inbox is flooded with people asking for Adarsh Balak t-shirts, especially the 'Swag' one.

Yeah, a lot of people have used that one...

... as their profile picture on Facebook, yeah. But it's only a fraction of them who have the sensibility to add a link to my Facebook page.

Does it feel weird when you randomly come across people on Facebook who are using your artwork as their profile picture?

It feels good, but yes, it feels weird as well. But I guess nowadays as a visual artist, you have to be prepared for it. It's so easy these days to just take an image off the Internet and post it somewhere. Sites like 9Gag that put their own watermark on it are the worst, though. 'Via 9Gag'. No, dude. It's not via 9Gag, it's via Priyesh Trivedi or via Adarsh Balak. I feel like the more paintings I make, the more likely it is that people will steal or borrow them or whatever.

“I feel like the more paintings I make, the more likely it is that people will steal or borrow them.”

The series has grown in popularity to the point where a lot of people are familiar with the paintings without knowing about the person who has made them. Does that bother you?

I've noticed an interesting trend of late: when someone posts my images on sites like 9Gag, there are enough people on 9Gag who know me as the creator of Adarsh Balak, and they add a link to my Facebook page in the comments, which is great. Recently, Diplo — I didn't even know who he was until a friend told me about him — posted my artwork on his Facebook page without crediting me. I contacted Diplo on Facebook and Twitter, and said that you can keep the picture on your page, but just add a link to my page in the caption or whatever, so people know where it's coming from.

Did he do it?

He didn't. He has, like, a million followers. He's too cool to check his Facebook page, man (laughs). But there's nothing more I can do. I think he himself got the image from someone who posted it on their Instagram feed. I can't even blame anyone for it, that's just how the Internet works. I think I'm okay with it as long as no one tries to monetise it.

You mentioned earlier that you don't like to be limited to any one particular style. With Adarsh Balak, do you think it's reached the point where people identify you solely with this one series of paintings?

Yeah, these days everyone calls me Adarsh more than Priyesh (laughs). That's something I don't want.

Do you think you'll always be known as 'the guy who made Adarsh Balak'? And do you think that's a bad thing?

It's not a bad thing, but I guess it's not entirely good either. To be honest, I don't see it as a problem at this point.

Do you think this series will open a lot of doors for you?

Yes, definitely. It's just been a month since I've been working on Adarsh Balak, and it has already opened a lot of doors for me.

As you mentioned before, Adarsh Balak has grown in popularity in a very short span of time, which can largely be attributed to the nature of the social Web. You've got more than 26,000 likes for your Facebook page in just over a month. These days, there are a lot of young people whose job description includes creating 'viral' content for the Web, rather than just creating great content. Do you think viral content can be engineered in this way?

I never expected or even imagined that Adarsh Balak would get the kind of attention that it has received. It was never my intention. I think that people like it because they see something that hasn't really been done before. It's the combination of nostalgia, and humour, and some screwed up shit (laughs). On the Internet, if you create and post something that's genuine and fresh, you won't even have to try to make it go viral. It just happens. You don't need any phoney marketing gimmicks. And more importantly, not everything needs to go viral.

“Not everything needs to go viral.”

What's next in the pipeline for you? Are you planning to work on any projects other than Adarsh Balak over the next year or so?

I have a lot of projects in mind. But there really isn't enough time for everything. I sleep a lot (laughs). I can't compromise on my sleep, because I can't work if I don't sleep enough. I barely work for five or six hours a day, which includes Adarsh Balak and my other freelance work. But I can only think of working on my other ideas after a year or so. I think that if you try to divide your limited attention over multiple projects, then you end up doing nothing right. It's better if I just stick to working on Adarsh Balak for now.

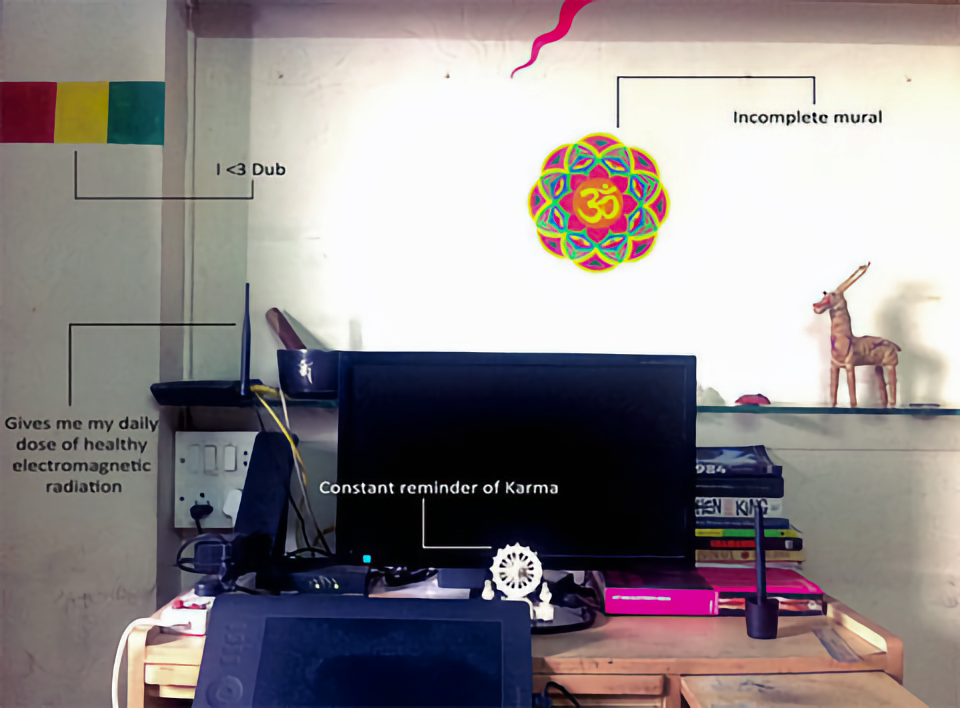

The Setup / Priyesh Trivedi

Priyesh's workspace.

"Desktop computer with illegal software. Wacom Intuos 5 tablet."

"Water colours, gouache paints, oil colours. Neon paints for the trippy stuff (and a black light to go along). Brushes of all sizes and shapes. Sakura Micron and brush pens."