"I'm just glad this is not a podcast," says illustrator Neha Shetty as we begin our conversation, "those things are too much for me." Hailing from Bangalore and widely recognised by her moniker That Zany Martian, Neha's work explores subjects and themes that span the surreal and the whimsical, the political and the deeply personal, perfectly complemented by her bold and distinctive visual language.

Read on for excerpts from a conversation with Neha about her formative years, her approach to visual storytelling, learning to navigate hustle culture, the value of sensitivity and optimism in creative work, and why listening to metal helps her stay calm.

Did you grow up in Karnataka?

Yeah, born and bred.

Where in the state did you grow up?

I spent the first few years of my life in Mysore. St. Joseph's School and Mysore. Mysore is just, I don't even know how to describe Mysore.

I love Mysore.

It's such an anomaly, in the best possible way. Mysore is… it's stuck in a time warp.

It is.

It is. It doesn't change. And I love that. I love that so much about that city, because the swing and the jungle gym I used to play on as a toddler still exist at the same park in the same way, with the same paint and everything. It's just so wild to me. I love it. It holds a special place in my heart.

I grew up with my grandparents around a lot. They used to take me to the fish market, the butcher shop, the flower market, and things like that. So, from an early age, my influences have been very rooted in local culture, more so than urban influences, so to speak. When you grow up in a city, you tend to have more of an urban influence. I don't think kids these days even know what the market looks like, to be honest.

You think so?

What do you think? What is a “K. R. Market”? They probably don't know about it, which is really sad, because the K. R. Market is so beautiful. There's florists around, it's like an explosion of culture and smells and colours. It's just beautiful.

You currently live in Bangalore. When did you move there?

We moved to Bangalore for my schooling. I hated my school days. I'm not going to get into it.

(Laughs)

I don't know if it is similar anywhere else in the country, but we have something called P.U.C., which stands for pre-university course.

Yeah, 11th and 12th grade.

Yeah. I mean, everybody does 11th and 12th. We do P.U.C. So that's what I did, at a state board college. And then I did my undergrad and postgrad at Christ College, Christ University.

What did you study?

For my undergrad, it was a triple major in history, economics, and political science, and I did my master's in international studies. And then I got into corporate work for about five to six years. The reason I’m saying this is because what I studied has nothing to do with what I do now. It's just so completely different. It's worlds apart.

I find that interesting, because I’d dropped out of college twice, and then went back and got a degree in biochemistry, of all things. And it also has nothing to do with what I do now.

Why did you take up biochemistry? Is it at all interesting as a discipline?

Looking back, I just wasn’t ready for college, and after dropping out twice, I realised that I didn’t enjoy formally studying things that I was actually interested in. I was always good at science in school, and I figured biochemistry was interesting enough for me to study in college, but not so interesting that I wanted to do anything with it.

I started working very early. My first proper job was at an architecture magazine of all things. And I currently run another magazine called Helter Skelter, but before that (from 2002–2009), I used to run this indie music magazine called Split Magazine, and an Internet radio/ music streaming platform called Split Radio with my friends Nikita and Ashwin. This is even before the whole SoundCloud era and before music festivals took over everything.

I'm really, really curious, so I’m going to ask you this, because I know I'm going to lose this train of thought before we go any further. What's your opinion on the music scene in India right now?

Compared to back then?

Yeah.

When I was running Split, the music scene was very, very different.

Right.

It was much smaller, not as many bands. There was more of a D.I.Y. culture around the whole thing. It felt very punk, the vibe, not in terms of genre, but just the way people did things.

Yeah, the kind of ideology behind punk, yeah.

There were a lot of talented musicians in the scene, but there was a lot of, like, let's just see what happens, let's have fun. We don't have to be the best, let’s just try things. There was a lot of that happening. It was a lot more difficult to access quality instruments and recording equipment and things like that. And, obviously, no big social media networks, and severely limited ways in which you could publish and promote your own music.

Do you think that because there was so much D.I.Y. before, the scope of being original was a lot more, so to speak? Do you think that maybe things are getting a bit more mediocre in terms of quality right now? I’m very curious.

I think one of the major ways in which it's changed is… Earlier, I think a lot of people wanted to learn to play instruments and form a band, and perform live in groups. I think now it's largely transitioned to, like, a solo musician thing. There’s easier access to high-quality equipment and different creative processes now. You don’t really need to be in a band.

Yeah, you can just be your own band.

Exactly. I've had conversations recently with people who used to play in bands around then who are still making music.

Right.

I think some of them have a harder time transitioning; I’ve heard them say things like ‘I’m making this album with a new bunch of people and they don't even know what side of a drum kit the drummer is supposed to sit on.’

Exactly. Exactly my point. Yeah.

I’m not sure that translates to mediocrity, necessarily. In the world today, with the kinds of tools available, is that even important? Do they need to know what a drum kit looks like?

But I think this also sort of ties into the whole generative A.I. and art thing that we have going on right now, right? You have people who are skilled workers and skilled artists as opposed to… I mean, I'm all for adapting and changing with the times, but at what cost?

There is something to be said for learning to do things before you break the rules.

Exactly.

I think social media platforms can tend towards rewarding quantity over quality, which, maybe, leads to the mediocrity you're referring to. No one can afford to take their time with things.

Yeah. Yeah. It's such a disservice. I mean, I don't know if you've observed this, but even in, let’s say, pop music, everything kind of seems the same. You know, it's so… the way I see it, it's just, everything is just different shades of beige, you know? Everything just seems so beige to me, but in different tones and undertones.

I’m so glad for my taste in music. I mean, I’m glad metal is still okay, it's alright, and so is goth and punk, thank god for that, but yeah, everything else… I don't know, man.

“I really enjoy listening to metal. As someone with an anxious nervous system, it really calms me down.”

I think we have similar tastes in music.

For me, there's a lot of fashion influences, too, that go hand in hand with punk, because of influences like Vivienne Westwood.

Yeah, Vivienne Westwood is legendary.

The queen of punk, basically.

Yeah, yeah.

Yeah, there's a lot of those correlations in the kind of work that I do as well, with chains and silver, with, like, scars and like, wounds and worms coming out of people and things like that. Yeah. And I really enjoy listening to metal—as someone with an anxious nervous system, it really calms me down.

I’m the same way. It's very hard to explain this to people.

I don’t know how to explain it. An over-anxious nervous system that is calmed by anxiously fast-paced music? People look at me like it can’t be a thing, how is that real? I don't know how to explain it, but it calms me down.

It also helps me get to deadlines faster. For example, if I’m working with a really tight work deadline, I’ll just put on, I don't know, ‘Hallowed Be Thy Name’ or ‘The Trooper’ [by Iron Maiden]. ‘The Trooper’ is really, really good for this. If you have a tough deadline, and you don't have the motivation, and coffee isn't doing the trick, put on that song, and you're good, you know? It has that galloping thing to it. I don’t know how to… it’s quite literally magic.

Let’s come back to Bangalore. Sorry about the digression (laughs).

No, it's alright. This is a conversation, so I guess we're actually sticking to the plan.

We are (smiles). I was curious whether Bangalore and living in the city informs the illustration work you do.

Yes and no. I draw a lot from my ancestry as well, as a Tulu person, as a Mangalorean, you know? [In my work] you will see a lot of folk and local iconography. There is general South Asian iconography as well, but a lot of it is specific to the language [Kannada] and Karnataka. An example of that would be a recent illustration I did called The Boar, where you can see the influence of my ancestry and how that informs what I do.

Sometimes it quite obvious, with Kannada being a part of the work, but also you'll see elements of Bangalore quite literally in my work, where I have, you know, portrayed the flower vendors and the femme vendors.

A few years ago, there was kind of a police brutality situation involving a lot of femme and woman flower and fruit vendors, and they bore the brunt of it. I felt like this was the sort of thing I needed to talk about. I can't just have these people as my muses, I need to talk about their struggles as well.

How do you like to approach doing that?

I like to keep myself informed through articles and independent journalistic sources, about the different struggles that women and marginalised communities go through. What triggered that particular artwork was an article that I read by an independent journalist on a website called BehanBox. They do really good work.

Then again, I also approach my work in this very typical zany way, there's a lot of sass involved, you know, a lot of goth-punk-ness involved.

Since you brought up ‘zany’, let's talk about the artist name and persona that you’ve adopted: That Zany Martian.

Basically, the idea behind the whole Martian aspect of it is… you know, a lot of people, including myself, have been alienated for a long time, because we, as marginalised communities and people, don't really find representation. We fall in the margins, right? And we get alienated very easily. I wanted to use a name that acts as a signal, a beacon for my fellow alienated people, whatever you may be, whether you're weird or because you are queer, or whatever. Like, hey, you do have a place in the small online community that I've got, in my artwork, in the conversations that I have.

Since ‘Martian’ is part of the name: does outer space hold any fascination for you?

Yeah, it does. I grew up with a lot of it… I was, I mean, I still am, a complete nerd and a dork. I’m a huge fan of science-fiction and things like Star Wars and the whole Alien movie franchise with Sigourney Weaver, you know? Also, H. R. Giger, the man who designed the Xenomorph, has had a huge influence on me. I'm a sucker for his work. Also, he's like a fellow Aquarian.

So am I (laughs).

(Laughs) I'm like, oh my god, of course, an Aquarian did that. Also, my parents were nice enough to fuel my curiosity by getting me books about space and talking about space, taking me to the planetarium, and things like that. I'm really grateful for that.

Has there been anyone in your life that has had a major impact on you as an artist? Are there people you consider to be mentors?

I’ve never really had a mentor, per se. But I am very appreciative of my family; my mom, my dad, and my maternal granddad. I was the oddball in the family, obviously, not the teacher's pet kind of kid, like my cousins were. My granddad knew I had a creative bent of mind, and he supported it, and encouraged me to keep going, as did my other grandparents.

They never made me feel like drowning myself in creative endeavours was a waste of time. And I really appreciate that, because I've heard a ton of horror stories and seen so many kids and people my age being lost to a very traditional field because their family did not support them in what they wanted to do.

“I wanted to use a name that acts as a signal, a beacon for my fellow alienated people. Like, hey, you do have a place in the small online community that I’ve got, in my artwork, in the conversations that I have.”

Could you tell me more about your journey with art and drawing as a child and going into adulthood?

It's very simple. You know how people grow out of drawing and being creative as they grow older?

Yeah.

I just kept going. I just kept that part of me going. I kept drawing. I kept a sketchbook for myself, even as an adult. I took a traditional route, like I said, in terms of my education, and my classmates used to be enamoured with my sketchbooks. What we were studying, political science and economics and stuff, everything was super serious, and I was doing something that was so way off [to them].

I really did want to pursue art more seriously, but then again, unless you’re a nepo child or come from serious generational wealth, pursuing art as a career is hit-or-miss, you know? Financially, you've got to be in a really, really good place.

Absolutely. I’ve always felt that not enough people talk about this.

Yeah. Art school is super expensive, okay? I did not go to art school. I'm doing this without any [formal] art practice. Everything is self-taught, right? For that reason alone, I thought maybe I should give the whole traditional thing a try, get some experience in the corporate world. Even if it wasn’t going to add to what I was moving towards, it would, at least, give me some sort of financial stability, allow me to take it a little easier, you know, when I did choose to go down an art path.

What was the transition like for you, from corporate jobs to working as an independent practitioner? Was it a planned transition?

It's a 50-50 thing. It’s hard to explain, but it was both impulsive and not impulsive at the same time. I had no design experience. I had no art experience. I had no freelance experience, per se, right? So I really had to think about it and plan things out, build that financial stability, but at the same time, I had already decided that I couldn’t do corporate any more.

Was there a definitive moment where you felt you had to jump?

The pandemic. People were dying, right? And I was like, listen, if I have to go at all, would this be a good way to go, being a replaceable corporate slave? I don't think so. I'd rather go doing something that I love doing. That's kind of what pushed me into going down the art path. Just... no regrets. No ragrets (laughs).

As you stepped into freelancing, did you have a vision for the kind of work you wanted to do?

At first, I didn't really know much about the kind of clients I wanted. At this point, years later, I know the kind of people I want to work with and the people I don't want to work with, even if, let's say, the brief looks good or the money looks good, right? But back then, I wasn’t very discerning, even if I had a sense that the client could be slightly problematic in terms of them not understanding my process or having unreasonable expectations about deliverables, or whatever, right?

I mean, it wasn't the wisest thing to do, sure, but then I don't regret that because I don't think, back then, having the kind of limited knowledge that I did have, I would have chosen any other way. It's really hard to talk about things in hindsight, and say, no, I would have done things differently. I don't think you would have done things differently. I think you would have done things just the way you did things back then.

Yeah, you do what you can with what you know, right?

Exactly.

Having done this for a while now, do you think your freelance practice has taught you to become more comfortable with vulnerability?

It gets me to be more comfortable with not having control and being okay with not having control, so to speak, and being open to uncertainty, because at the end of the day, that's how life is. When you're a freelancer, everything is on you. In corporate, it's not. You have a boss, you have H.R., you have other people taking care of things, right? I think being a freelancer really does teach you a lot about self-discipline.

Would you say you’re a disciplined person?

Yes. Then again, I wouldn't say that out loud.

Why not?

I just wouldn't say that about myself. It's something for others to say about me, rather than me saying that about myself.

“I really hate that sensitivity is considered weak and immoral. Sensitivity holds so much power, and you’ll see that some of the best artists, the most creative people are people that tap into sensitivity.”

I’m curious about how you view being disciplined in the context of hustle culture (and the pressure to constantly push yourself) versus the idea of finding contentment as a practising artist.

I do think the whole pushing yourself is only half-true for creatives. We're really sensitive to the world and our environment, and I really hate that sensitivity is considered weak and immoral. People need to stop that. Sensitivity holds so much power, and you'll see that some of the best artists, the most creative people are people that tap into sensitivity, right?

And because we're so sensitive to things all around us and our processes, I really do think creative people, as passionate and driven as they are, should take the whole ‘pushing yourself’ with a grain of salt, you know? Give yourself and your art the benefit of doubt, and the benefit of listening to yourself, rather than listening to people around you who may or may not be aware of your journey, how powerful your voice may be, and what it needs.

Each one of us has different needs, right? Some of us are very logical and rational, and we thrive in that. Some of us are not. I think it's a subjective thing. Listening to outside voices who say push yourself, drive yourself can only take you so far. It's going to do more damage than actually help you, I think.

Do you think social media engenders a sort of pressure to perform discipline and success?

You know what it is? I think it has a lot to do with financial uncertainty. And I get that. Especially for freelancers, the kind of economy that we live in can make things a little dicey.

What you end up doing in that situation is that you kind of convince yourself, oh, the only way I'm going to make it out of this is if I actually push myself in a way that doesn't look like I'm pushing myself, for the world outside to see. Oh, look at me, I'm waking up at 3 a.m. and I'm doing that and doing this, you know, whereas what you might really need is, like, maybe getting a good night's sleep, waking up at 10 a.m., and then going for a walk and checking out, you know, sending a bunch of cold emails and, like, talking to your friends, things like that. What you are doing in that case is living for someone else rather than yourself, and that's very counterintuitive.

Grinding is okay, but whom are you grinding for and what are you grinding for, and to what extent? I think that’s something people should take the time to consider.

That’s a great answer.

Thank you.

“Grinding is okay, but whom are you grinding for and what are you grinding for, and to what extent? I think that’s something people should take the time to consider.”

I think it is something people do struggle with, drowning out the noise and taking a moment to just think about what's important to you and why you're doing this in the first place.

Yeah, I mean, we're all guilty of that, and it is normal. We're humans, right? We're not robots. It's just about how much of that noise you let in, you know? How many cooks do you need in the kitchen? Do you need any? Do you need just two? Whatever makes the recipe work, man. Maybe you need ten cooks, maybe you just need five. I don't know. It’s for each person to decide for themselves.

I’ve followed and admired your art for some time now. I quite enjoy how integral storytelling seems to be to your illustrations. I know that you do a considerable amount of editorial work, but even in your standalone illustrations, I get the sense that there’s an entire story contained in each one. Is that something you strive towards?

I think the way I approach my work is a bit… I don't know what to call it, a neurodivergent way. I kind of zone out. I really do zone out. I lose track of time and everything else because I'm so ingrained to what I’m doing and what I want to do and what I want to say that it's just... I'm not conscious. I mean, I am conscious, because I have to draw (laughs). But it's just like auto-writing. I just keep going. And when I’m done, I look back and it's a whole new artwork, do you get what I mean?

Absolutely.

It's like a trance. I don't know how to explain it. It's like you've literally been possessed by your own work.

Do you like to take your time with your illustrations?

When I have an idea, I draw a few elements in, and then I let it gestate, you know? I just let it be. I give it a few days to a few weeks. Some of my illustrations that you see online might have started like a year ago, right? But in that time it's evolved so much that it's a completely different work now, with something else to say, because I’ve grown and changed as a person and I look at things differently.

The storytelling also changes according to that and how I view the world now as opposed to how I used to view the world [when I started the work].

That’s very interesting. I find it very difficult to revisit and revise my work over time.

For me, it’s about how the art takes shape, right? I mean, to me, it's not done unless I'm fully convinced it's reached a certain stage. It's a knowing. An illustration I’m working on might look complete to someone else, but for me, there's still something missing, right?

There have been so many times when people have looked at my artwork, and I keep telling them ‘there's still a few details missing.’ And they don't get it. I'm like, no, trust me, there's something still missing.

I have to give my artwork a chance to like live its own life for a bit and take its own shape. And then it will inform me whether it's done or not.

It's important for you to kind of step away from it for a while and then come back to it.

Yeah, because that's the pact I made with myself and my practice and my creativity—that I let it have a life of its own.

Are you an optimistic or pessimistic person? Do you think either of these traits are useful for practising artists?

I'm realistically optimistic, because I have to be grounded in reality if I have to, well, live to see another day. I feel like I have to be optimistic. I’ve tried pessimism—it doesn't always work, and it doesn't do any good, to be honest. Optimism works better, and is important as it relates to self-belief. I don't think anybody else is going to believe in you unless you do that to yourself and for yourself.

“I'm not a traditionalist in any way, shape, or form in my life, but isn’t technology supposed to make life easier? Why is it being used to do the opposite?”

How do you cope with failure?

Coping? What is that?

(Laughs)

What is coping? I don't know her. Do you?

(Laughs)

Just in the past two years, with the prevalence of technologies like generative A.I., so much has changed when it comes to creative professions. Do you find that stressful or exciting?

It's very dystopian, but not in a cool way like they show in the movies. I just want A.I. to make my life easier and not to take my job, you know? I think A.I. has its uses, but I do think it's not being used in the right way or for the right purposes. I'm not a traditionalist in any way, shape, or form in my life, but isn't technology supposed to make life easier? Why is it being used to do the opposite?

I get so infuriated when people play the whole whataboutery game when it comes to generative A.I. It’s literally stealing people's work and then you have people saying, yeah, but it’s what happened to portrait artists when cameras came about. It's not the same thing. Photographs don't steal artwork, they just capture images, and a portrait artist is literally creating a whole new piece of work.

It's two different things. And I just, I don't know how to explain this to LinkedIn bros. I don't any more; for the sake of my I.Q., I really cannot do that to myself. My energy and time are too finite for that.

It makes me angry that people who are stupid and undeserving have the kind of resources and the money that they have, when there's people like myself and others that I know who deserve to have those resources, you know?

Do you think that artists have a responsibility to be good people?

Morally good, you mean?

Yeah.

The way I look at this is: an artist has to serve people. Art has to serve people, right? And that's how I see myself as an artist, which is why I support causes that I'm passionate about, and you'll see glimpses of that reflected in the kind of work that I do as well. You look at Picasso, right, and the kind of asshole that he was, and you ask yourself, is the art he made and his legacy even important when he was that kind of person? And I think that's a question that people need to answer for themselves. What's important? The artist or the art?

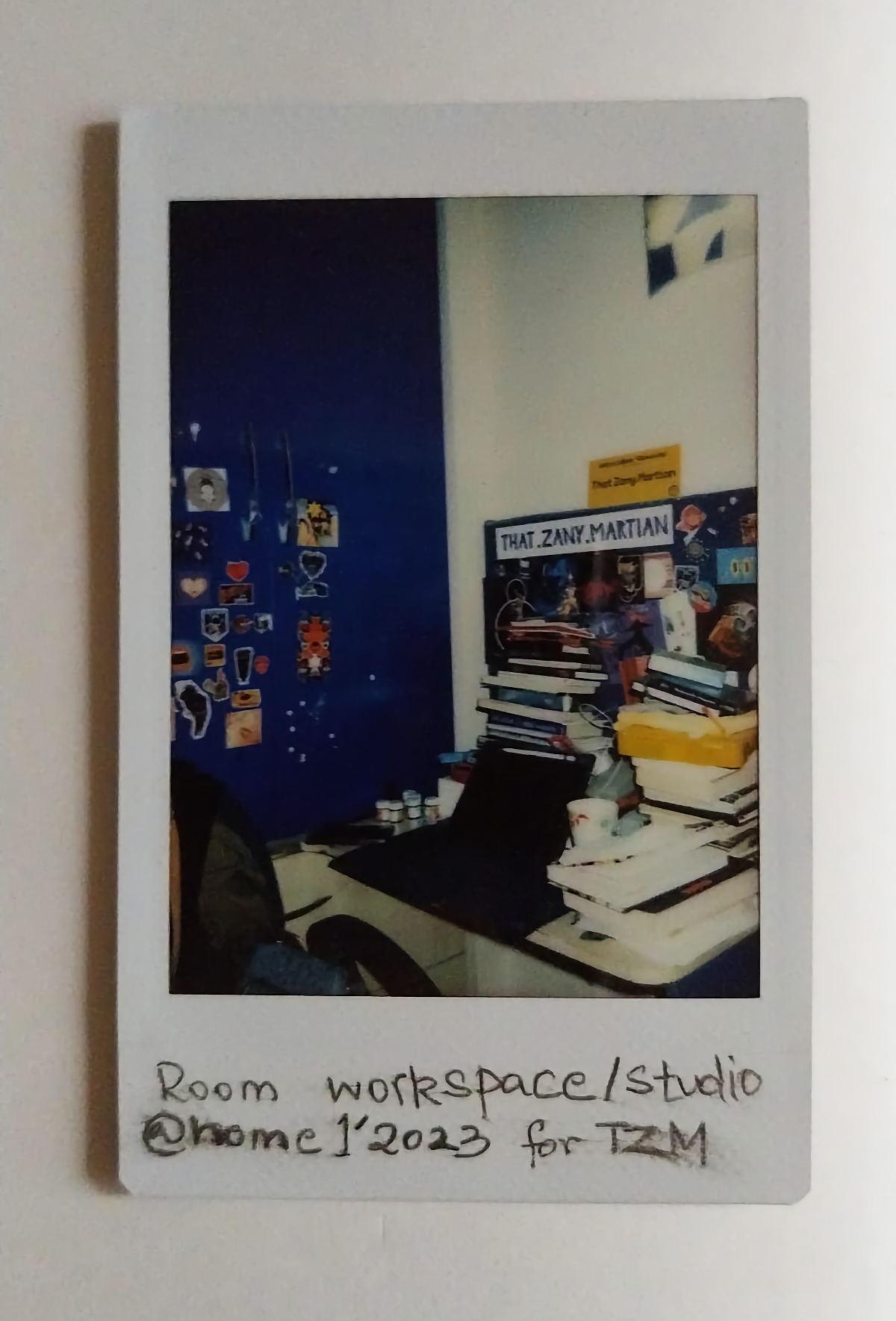

The Setup: Neha Shetty

"I use Procreate and Adobe Fresco on an iPad for most of my digital illustration work. When I go analogue, I use Mungyo watercolour crayons, Camlin brush pens, Posca markers, and regular HB mechanical pencils. I prefer sketchbooks with 230–250gsm paper, because I like to experiment with markers and watercolours and I don't want my sketches to bleed through. "