“I think our generation is lucky,” says illustrator and printmaker Mrinalini Sen, “because we didn’t have social media to contend with when we started making things.” As we talk over coffee on a languid Sunday morning at her studio in Goa, she continues, “I think it’s been unfair for kids who have had to grow up with it, because it’s now solely about validation. You know, the joy you find in sitting quietly and reading and making is diminishing.”

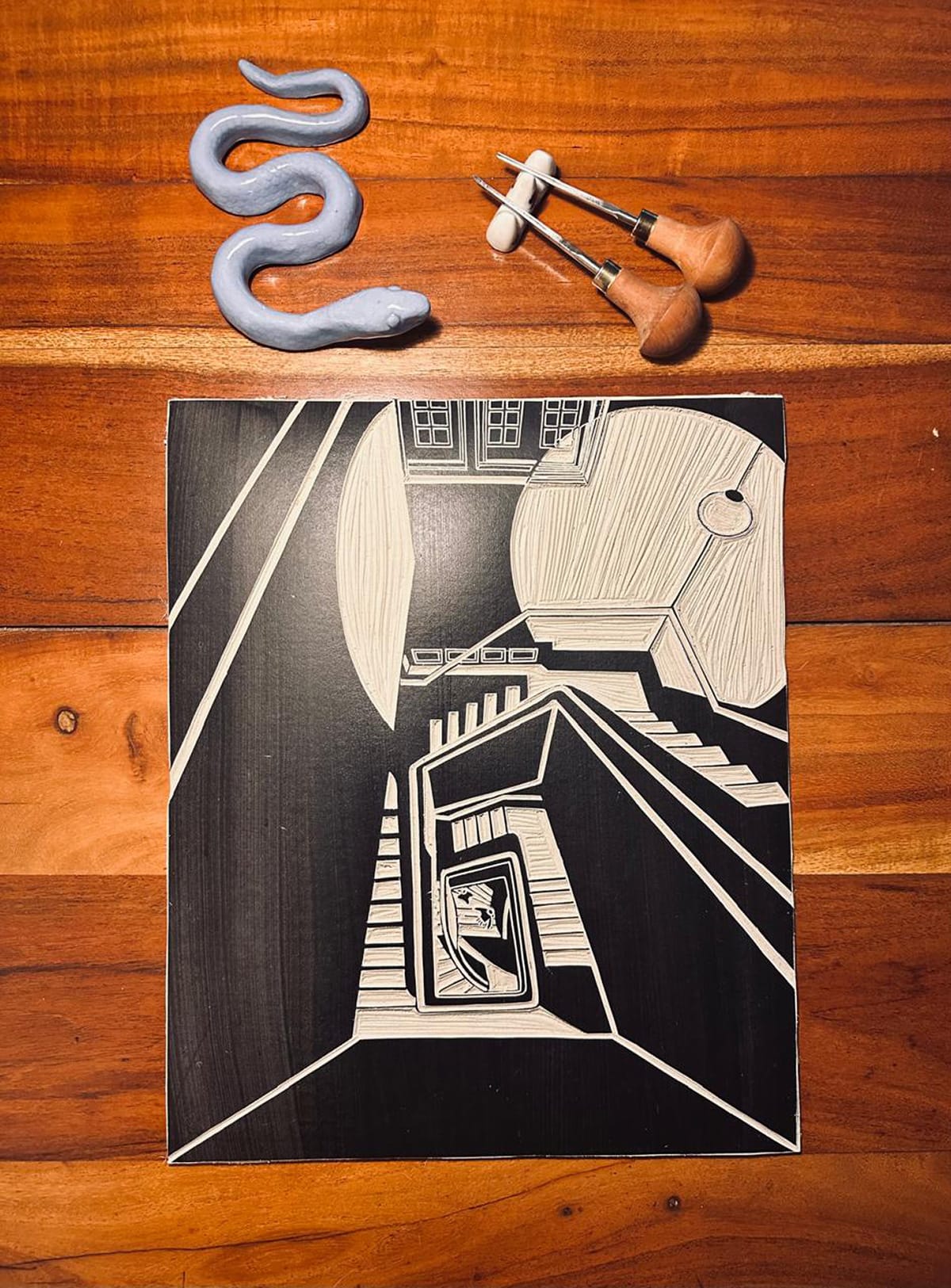

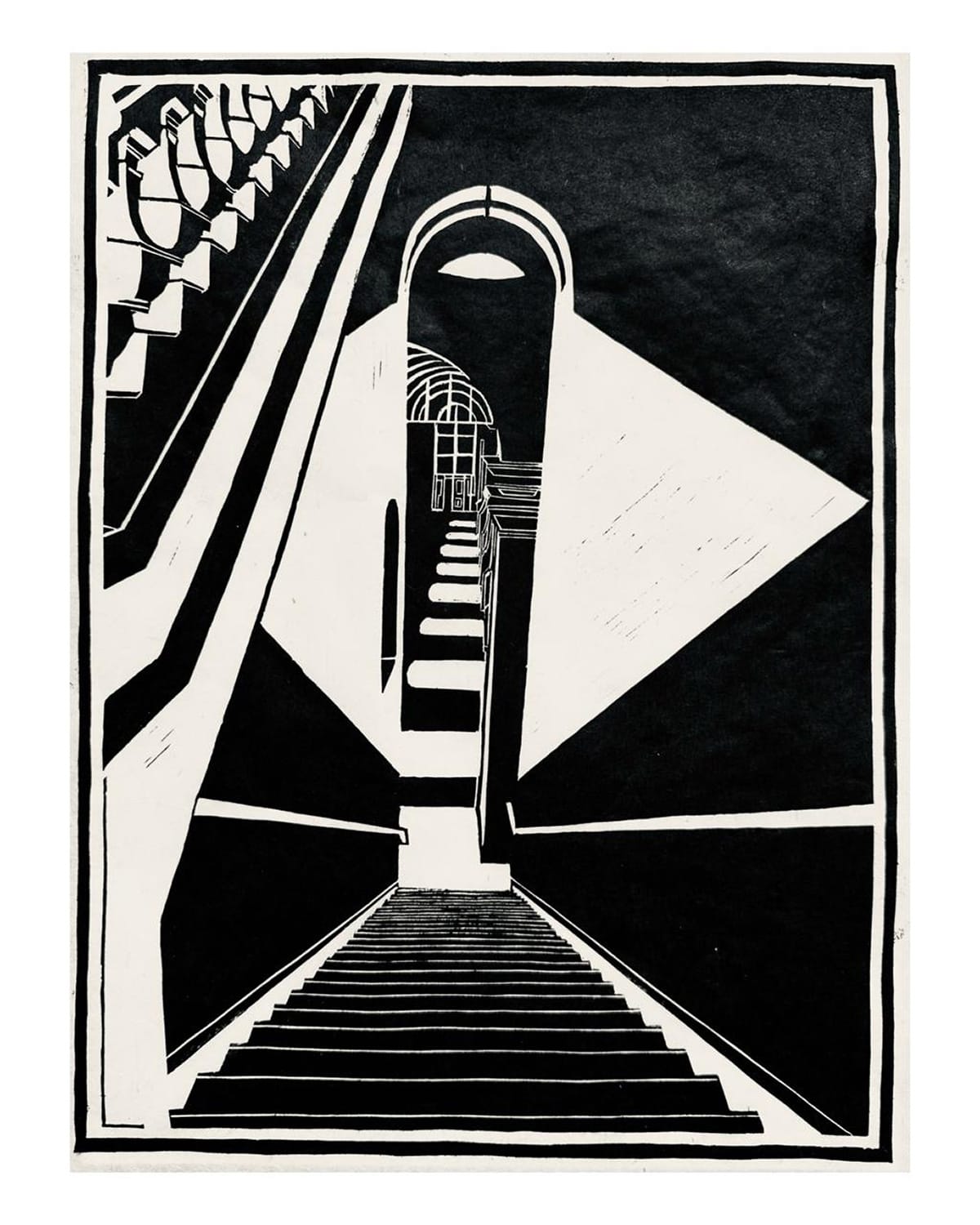

Raised in Calcutta and now a longtime resident of north Goa, Mrinalini’s practice has spanned multiple mediums and tools. Her linocut prints explore scenes and themes that begin in the familiar and slip, almost imperceptibly, into the otherworldly. Each piece becomes a self-contained story, told through the interplay of light, shadow, and gesture, both rooted in reality and gently untethered from it.

Read on for excerpts from a conversation with Mrinalini about growing up around artists, the influence of architecture on her work, her artistic vision and love of tangible mediums, navigating online spaces as a creative person, and the importance of celebrating introversion.

Tell me about your early years. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Calcutta. I went to school there, I went to university there. I spent most of my formative years in that city, and we moved around [within the city]. As a child, I lived in northeast Calcutta, in this place called Beliaghata, which was a nice [part of] Calcutta in terms of the architecture. A little bit of art deco there. I used to cycle around in the neighbourhood. It was an old Calcutta in a sense, but not too old, not as old as north Calcutta itself.

When I was around seven, I joined La Martinière for Girls, the boarding school. I noticed the way the architecture around me changed, from Beliagata, the buildings, to the space in La Martinière. That made a huge mark on me as I grew up.

As a young person seeing and perceiving different spaces, what aspect of architecture interested you? Was it the forms of the buildings? Was it the way spaces flowed?

Mood, I think.

The way you felt when you were in those spaces?

Yeah. I think mood was a big part of growing up. Light and mood. My father was always very keen to point out light in different times of the year, seasonal light. So how the winter light hit my home in Beliaghata, how summers were in the grand colonial architecture of La Martinière. And just being in a space with a book in solitude was a large part of my growing up.

It was such simple access to joy. And such direct access to joy. Free, as most things are when you're young.

I think I became a very solitary person as a result of it. Perhaps. But it also helped me to start building an inner world. And, of course, art has been there for as long as I can remember. I think I started making stuff when I was four.

Drawing stuff?

Drawing stuff. And I remember telling my kindergarten teacher, who still remembers it to this day, that I’d like to be an artist. And I still feel like I want to, I’d like to be one. I don’t think I am one. I think it takes a lifetime to be able to be that, or even close to it. But it’s been there all my life.

Spaces, moods, solitude, developing a visual memory, all of it became a part of my growing up. And Calcutta made a huge impression on me growing up, as any place would in your formative years. I don’t say that I love the city, you know. Honestly, there are aspects of a place, wherever you grow up, that affect you negatively. But overall, I can’t deny how much of a significance it's had on my mindscape.

“I remember telling my kindergarten teacher that I’d like to be an artist. And I still feel like I want to, I’d like to be one. I think it takes a lifetime to be able to be that, or even close to it.”

As a child, do you remember feeling like you loved the city?

As a child, yes. Then as teenage angst comes, everything around you becomes a target (laughs). And, of course, the city became one then.

I mean, I loved it. But, you know, you have experiences, you’re trying to understand things, you’re confused, you’re irritable, you’re all of those things. And it’s happening in this environment, which is so familiar. It is a bit of a village, the city, everyone knows everyone. So it can get a little claustrophobic, unlike, say, a Bombay, where it’s so wide and so big, and you can be so anonymous.

You mentioned your father, who is also an artist. I’d love to know more about him and his influence on your work.

Sure. He's very reclusive. He is my primary influence. I had the privilege of growing up around a practising artist. What that did for me is that it exposed me not just to the grandioseness of the artistic life of where you’re thinking and you're immersed in beauty and all of that, but also the technical nitty-gritties of it, how much of routine there is involved in the practice, how setting up is a ritual, how doing the work is a ritual, how cleaning up after yourself is also a part of this process.

And it exposed me to the process, to mediums, to what things smell like, what things feel like. So, for example, even linoleum that I’m working with right now, comes from one of my earlier memories of watching my father make [art using] linoleum. Calligraphy… even though I don't practise it, but he's a calligrapher. It's one of the things that he practises. So line work is very important to my creating and making of things. I’m probably, in an imbalanced way, more focused on line work than I am on colour. That comes from watching my father practise line work every single day.

Also, the life that it involves. It’s not just about making beautiful things. It’s a lot of grinding. It’s a lot of sticking and sticking to something even when things don’t work out. There’s disappointment, there’s suffering, and then there is euphoria and rapture, all in one.

My father continues to make a big impact on me because he is somebody who started working and creating when he was five years old and he’s 73 now. Not a day has gone by when he hasn't stuck to his routine, waking up early in the morning, working until night and really cutting out all of the noise.

I’ve had and have, of course, masters that I look up to and artists that I am completely enamoured by… they inform my practice and I strive for the best I can do. But just having a living person in your life who has such a primary influence on you… I mean, I don’t think I'd be here without my dad, in that sense. I think he really directed me subconsciously into knowing how I wanted to live my life more than making things.

You’ve told me before about how you value ritual in your practice. How did your own rituals and process evolve and how do they inform your work?

The way I usually work is… I get possessed by a piece. So I’m not one of those people who sits down, does a piece, gets up, neatly compartmentalises into the next piece.

I see it in my head. I chase it. And then when I’m making it, it’s a flow, a flow state. I draw it. I'm obsessing about it. It consumes me. I put it down on paper. I draw it several times over and over again. I struggle with perfectionism, struggle with trying to get it exactly right.

Sometimes in that struggle, I discard it or come back to it later. But often, I don’t. So the process and the ritual really involves seeing it in my head, sort of spacing out, and seeing it in my mind’s eye. And I think the journey from the mind's eye to the paper and what gets lost in translation there is really my ritual. I try to not lose it in translation, but of course, I do. There is some erosion.

And I work better early in the morning or late at night because distraction is a thing and an epidemic I think we all face. And I, of course, have a day job to be able to keep my practice sacrosanct.

So, yeah, that’s kind of it. I get consumed. I have a piece, I see it, and then I just make it. Then I take a little time off. I let it go. I forget about it as soon as it’s done. And I start to think about seeing something else.

“It’s not just about making beautiful things. It’s a lot of grinding. There’s disappointment, there’s suffering, and then there is euphoria and rapture, all in one.”

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of losing things, ideas, in translation. Do you find that, sometimes, you gain things in translation as well?

Yes. Yes.

You know, those moments where your own brain surprises you.

Yeah, that happens. Interesting you ask that because I look forward to those moments when they do happen. I’ve noticed, perhaps this could be a common experience for other people, but it's always easier to edit work than it is to come up with it. When I leave a piece behind, I'm like, I don't want to go into it.

Like, I’ve made this skull and then I’ve made the skull again for another piece. And I’m keeping on doing the same one. I sometimes see things later, which I didn't see in the original conception, and of course, build it in. If it’s something that changes for it to elevate the image, I build it in. But that’s rare, Arun, it doesn't happen very often. It’s something that is serendipitous. I don't know. This is kind of like, it’s like the realm of magic (laughs).

That’s one of my favourite things about making art, how without doing it consciously, you’re learning about yourself through the art you’re making.

It is, right? I was having this chat with a friend about the impact art makes, and it’s really to the subconscious. It’s not measurable. You can’t say this is how many people it’s actually hit.

The fact that we pluck things out of the subconscious changes us and changes people, hopefully. One can hope that it has moved someone. That’s the greatest compliment anyone can give you. But if it does, the movement is so deep within and it's so imperceptible. You can’t really measure this stuff. It’s in waves. It gets into you, it gets out of you.

You’ve been working with linoleum for a while now, but you also do a lot of illustration work on paper and on your iPad. How important is the sense of tangibility to the art you create? When do you begin to think about the medium you work with?

The medium is a phase, in many senses. Right before linoleum, I was immersed in gouache as a medium because of the opacity, because of how I draw and how I see and colour. I embody that particular medium for a little while until it’s in my system.

Now, linoleum's taken over me because it’s so tangible, right? You’re drawing on paper and it's a composite skill to be able to do printmaking, because you’re drawing and you get to practise your pencil work and your line work. Then you're painting the linoleum and you’re actually physically carving the lines with a tool. Then you’re getting the printing work done. So all of it together is such an enjoyable process. There’s so much diversity within the creation of one image that currently that's all I want to do.

Sometimes, I think, oh wow, I’m just constantly working in black and white. Colour is beautiful, it’s a world, but I know that if I go into colour world now that I'll have to abandon this. For me, it’s hard to. The medium also dictates the kind of work I do.

Currently, it’s lino. I have no plans per se of shifting mediums or choosing a [new] medium. Usually, it’s something that appeals to me, like I’m now starting to look at videos of copper plate etching, because printmaking is something I’m very intrigued by and there’s no agenda. It’s a process that appeals to me. Who knows, maybe in a few years time I’ll start looking at etching as a form.

It’s also the artists that inform my medium. There are a lot of artists, like Gustave Doré who illustrated Dante's Divine Comedy. One of my favourite artists, one of them up there on the wall over there. Incredible, incredible detail.

Again, copper plate. Now, that’s the thought I'm nurturing in my head. Do I want to go into that someday? And it’ll happen, hopefully. I hope it does and then I’ll be consumed by that. So, actually, the medium is a big part of the phase or the mood I’m inhabiting.

Did you formally study art?

No, I’ve never studied art formally. I’ve learned a lot of technique from my father. He studied art formally at Government College [of Art and Craft]. He’s an artist. He did his B.F.A. and M.F.A. in printmaking. So I picked up a lot of stuff from him. I’ve had a lot of art books around. A lot of my dad’s friends are artists. So there’s been a lot of that environment. But I decided very, very, very early on in life that I was not going to earn a living from my practice. Maybe it was my environment. Maybe it was seeing the lives of other artists.

I knew that [art] is so sacred to me and a source of joy for me. And I knew that if I started trying to make money from it as my primary way of making money, I could risk having to corrupt it. Maybe corrupt is not the word I'm looking for… say, contaminated with something.

Currently I’m in a place where I draw only what I want. And, of course, if there are projects that I’m interested in, I’ve managed to have some amount of a livelihood even from art. And I’m very grateful for it. But I’m also happy that it wasn’t something that I started off with right from the beginning. And I deliberately chose to study something else that could give me a day job.

A lot of my art role models have said the same thing—hold down your day job. Like Stephen King, whom I love reading, had a job for several years. He was moonlighting in the evenings, writing his books. Amazing storyteller. Jerry Garcia said keep your day job. I think I took that advice very seriously, and I’m glad for it, because it gave me the freedom, the absolute, sheer freedom to do whatever the fuck I want to do with my art.

“Currently I’m in a place where I draw only what I want. And I deliberately chose to study something else that could give me a day job.”

What did you study in college?

I studied literature. And then I went on to do a course in linguistics and pedagogy. And I work as an academic, a teacher trainer in linguistics and language studies.

I think the first time I came across your work, what really struck me was that each standalone image tells a complete story on its own, in one frame. Is that your intention with your linocut pieces, or does it just happen that way?

I love it when something I’m trying to do is received (smiles). Thank you, Arun, for noticing.

I have lived with stories for a very long time, for as long as I can remember. You love reading, Arun. I love reading. We know how comforting it can be to live with words. Words have probably been as much of an influence in my life as drawing and art. So to answer your question, I’m not setting out to tell a story when I'm looking at an image, but invariably I end up [doing so], because I'm trying to convey a mood.

The three things that take centre stage when I’m drawing are space, solitude, and mood. So I very rarely have more than one or two people in my images. It’s those people in a space at a time, at a specific time. And these three things seem to come together. I don’t plan for it. It’s just the way I see to represent life forming in something that's not alive.

A space can come alive with a being in it. And these are the ways in which I guess a story gets told in my head, which may or may not be received in the same way to someone who’s viewing it. I’m not very good at portraits and people, because I’ve naturally never really been interested in drawing people. But, you know, I think that it’s important to be able to, that's something that happens when you start drawing something, even if you’re not into it, you start seeing more with it and incorporating it and building it into your work.

So, maybe, in the future sometime, humans will take more space [in my work]. But at the moment, I like to keep them at bay.

Speaking of solitude and a sense of place, you live in Goa now. Did you seek out Goa for the solitude it offers and the kind of space that you have here? And how does this place inform your life as an artist?

Very much solitude, very much my introversion, which I celebrate. I don’t think introversion is celebrated enough. And I think that there is a power to that sort of a life, which is very different from an extroverted life, which is, of course, how the world is run, by people who can talk to other people and communicate and all of that. That’s great and it has a place. But I think that if you’re of a bent of mind where your best work or your best thinking or your best feelings are done alone, or with a select few people, you owe it to yourself to make that life for yourself.

I felt that very strongly after living in a city for all those years. I mean, I moved here when I was 31. So it’s been six or seven years since I’ve been in Goa. And the choice was to get away and to find quiet and to keep a very small set of people in my group of friends and to focus and zone in and flow with my art. I was lucky at that point to have had a remote job. I could work out of anywhere.

And I decided to move to Chorão Island, which is possibly the farthest one can get from the city (laughs). It was quite a… it was a deep dive. It was psychedelic, in every way. It was quite a bit of a shift. And I’m so happy I did that. I didn’t have electricity a lot of the time. I didn’t have the Internet a lot of the time. This was before the pandemic, so not a people had moved here. And yeah, it was a very conscious decision to get away and to celebrate introversion and to live that life.

People said don’t be too cut-off, you know, you could go insane. And I think that you mustn’t lose your insanity. I think you need to hold on to it if you've been blessed with it, because everything is just far too normal, you know. And I did that. That was the plan.

Chorão is an interesting choice, quite removed from a place like Porvorim, say, which is also part of Goa but a little more urban. Chorão is very quiet, very isolated. Did you find that transition jarring?

I think I was exhilarated. My art, my work blossomed. I was making so much more. The distraction and noise just cuts away. There’s so little to do. And if you are lucky enough to be an introvert and have an inner world that you’ve nurtured, that starts becoming louder. Of course, in terms of convenience, it was very inconvenient. It wasn’t an easy life.

“I think that you mustn’t lose your insanity. I think you need to hold on to it if you've been blessed with it, because everything is just far too normal.”

I think there’s one restaurant on the island (smiles).

There’s one restaurant. So, if you’re not cooking your eggs, you go once every two weeks to stock up from someplace off the island. There wasn’t a departmental store or anything there. There was no gas there, so you're constantly checking if your car has fuel. You know, it’s a change. You’re really going off-grid in a sense. But what it does to your head, or did to my head… I don't think you can buy for the most expensive rent in the best parts of Goa, particularly, if that's the kind of person you want to be or the kind of life you want to lead.

It is isolating. I was lucky to have a few people around. And that was enough.

Did living on the island lead to you radically new ideas, things you hadn’t considered before? Or was it more of a slow expansion?

I did two series when I was in Chorão. I was going to my gouache phase at that point. So it was all colour. And Chorão is just vivid, you know, it’s so psychedelic. It almost looks and feels like you’re inhabiting an acid dream every morning. There were a lot of animals in my work at that time, because we saw a lot, you know, fruit bats or snakes or crocodiles or birds.

That was one series I was working on. I also go to the mountains every once in a while, and I had done sketches when I was in the mountains. I’ve been to Uttarakhand a few times and I plan to keep going. And I had done a trip where I’ve been around Trishul and Nanda Devi and Chaukhamba, a few of the other peaks. And I'd done sketches while I was travelling, of the peaks.

That, and because of the light in Chorão… the light was just so incredible, you know, the dappled light through the trees, the sunsets, the expansion… Light became, and it still is, a big part of my work. And I made my mountain series then called Mountains of the Mind, which were from that mountain trip. I work so much from memory, and the light really helped me bring those images to my mind.

Do you view yourself as a pessimist or an optimist?

I’m upbeat. I look forward to life. I love life. I love living. I’ve had hard times and hard knocks, but I don’t know, call it foolhardy, idiotic gusto, but I like to say, hit me, give me what you’ve got (laughs). There is a lot to see. There is so much to learn and know. I mean, my head reels at just the number of books I have left to read. Like, how much time do I have? (laughs) You know, there’s so many comics, there's so many books I have to read, there’s so many films I have to watch.

And, maybe to a fault, I kind of push aside a lot of negativity. Sometimes it’s important to process that, as well, but because I have my work and my art, it’s always been my coping mechanism for everything in life. I feel like I have a system, where if I’m a little down, like everybody has bad days, I can zone in and I can forget. And maybe that suppresses things and probably affects me later in ways that I don’t understand. But overall, my disposition is, let’s get up and let’s move on and do. I think I like to do, you know?

I think that’s very cool: your art is something that no one can take away from you. No matter what happens, that's something that's always yours. It will always be yours.

That is precisely it. I protect it with my heart and soul. It is mine. It is the only thing that I can call mine in this world. Everything else is everyone else’s. I can’t possess a person, I can’t possess anybody’s will. All I have is my work. And nobody and nothing can take it away. If you blind me tomorrow, I’ll paint with my mouth or I’ll build something with my hands. If you cut my hands off, I’ll find a way. I’ll find a way to express. And I think that has been a source of huge strength for me.

That’s probably why I feel less worried or anxious about what life throws at me. I’m going to get bitch-slapped, well aware of it (laughs). But it’s okay, because I have a way to deal with it.

And yeah, so upbeat and very, very pro-living. I want to seize my life and take it by the horns.

You mentioned that you’ve tried to make sure that your art is never your primary source of income. Just in the past three years, so much has changed across creative professions and communities. Due to the pressures imposed by the economy and social platforms like Instagram, so many creative practitioners seem to be struggling with staying true to their vision and process while also trying to make a living. As a creative person, one needs the time and space to experiment, to get bored, to sit with yourself. Do you think the scope for doing that has reduced?

It’s a very important question. Is the scope reducing? I think, yes, there is some mounting pressure on creators to keep producing work on a metronome and keep putting it out there. And that’s not how the creative life is. You have to get bored, you have to get blocks, you fight the block, you have a horrible thing happen to you, and you deal with it, and you come back, and it’s not always on a beat that, you know, that Instagram needs. And having said that, of course, I think social media is demonic in every possible way (laughs), especially for creators, because you’re asking them to stop having their own rhythm and submit their work… you can't make good work all the time and put it up all the time. A lot of the work you make is shit. And you cannot be put on this constant expectation of delivering high quality work every week. And if you’re depending on social media as your main source of income, you will face burnout, you will question yourself, you will question what you’re doing.

And all of that is, I think, is one of the worst things that can happen to the creative life. Yet, there is a way for people to be able to use it as a tool. And there is a way to manipulate and hack this in your favour. And I’m still exploring this, I don’t know the answer. But I’ve been fortunate enough to see that there are some ways you can insulate yourself from the demon that is social media. Sometimes I find myself putting up things that I regret. And it’s a constant questioning of yourself.

“I protect it with my heart and soul. It is mine. It is the only thing that I can call mine in this world. Everything else is everyone else’s.”

The truth is, people forget. They see something, they’ve forgotten, people only think about themselves, nobody really cares. But as an artist or a creator or a maker of things, you are questioning what you’re doing. And then you’re putting yourself out there, your very vulnerable self, what you’ve made, out there. So you’re double-attacked, once by yourself, once by what the world expects of you.

I think the way to go about it, if there is anything that I’ve learned from the process, is to streamline it to only the things that you want to expose. Social media is not real. I stick to the work I’m doing. I am a private person, I try not to put up private work and private life, things other than what’s relevant to my art. And that has served me well. I think it has protected me to a certain degree.

I am very vocal about the fact that I dislike social media. I find it disruptive. I find it to be unpleasant to the process of making, and for two months of the year, I deactivate my account, regardless of whether I lose followers or not. Doing that gives me the clarity and the focus I need, and the time I need to make without judgement and without pressure. Fighting the algorithm is important.

‘Social media is not real’ sounds like a very simple and obvious statement, but it’s scary how much of reality it distorts. Some of the smartest people in the world are hired to make these platforms more addictive. It’s not by accident. And quitting social media isn’t really a solution, because everyone else you know is on social media.

You get on top of it. You’ve got to get on top of it. Be kind to yourself first, you know, remember why you’re making and see it for how distorted and unreal it is. I think social media keeps forcing you to compare, and art cannot exist in competition and comparison. It cannot.

It exists in its own being and beauty, for what it is, you know. And you have to keep reminding yourself that it's a struggle. It’s probably one of the hardest parts of putting your work out there right now, and it’s hard enough, anyway, to create.

A selection from Mrinalini Sen's Mountains of the Mind series of gouache paintings, featuring prominent peaks in the Indian Himalayas.

Do you feel that contentment is overrated?

Do I feel contentment is overrated? No, no. Do I think contentment is a status quo state of mind? No. I don’t think everyone is contented. I’m not always content with everything. There is discontent and that has a place. If you’re not questioning, you will continue to think your work is amazing. You shouldn’t (laughs).

I think it’s important for you to question the work you do. And that causes discontent. It’s part of the process. But when [contentment] does come, when it does appear, savour the moment, because it doesn't come very often. Enjoy that feeling with regards to making something. Enjoy that feeling of, okay, that was a day well spent. I think we’ll go to bed happy. So it’s not overrated in that sense.

Do you want to be content all the time? You can try. It’s a good plan. I don’t think it’s entirely achievable (smiles).

Your day job involves teacher training and working with young students. Have you ever considered mentoring young artists?

I don’t know if I can, if I’m qualified. The only thing I have considered and have done in my language studies classrooms often is to use origami to teach listening skills. And that is something I really enjoy. To be able to listen clearly to an instruction and follow it through and then to make something tangible with your hands has served a lot of kids well. It’s piqued their interest.

If there's anything I would like to do, it is probably, you know, in the realm of craft, because art is intensive. It takes time. It’s messy. Most things look like shit in the beginning and a lot of people can give it up. But craft is more of a gateway into making, I feel, because you can start with something small and then you can really go wild with it. And oftentimes, when you start with something small and you have small achievements over time, it’s those small achievements that lead you to want to imagine bigger things and take on bigger projects. And yeah, I’d love to do something like that, actually (smiles).

“I think something handmade is invaluable and even more relevant in a digital landscape where everything is generated and, you know, keywords are typed in to make something.”

I enjoy teaching kids. I think children have way cooler brains than adults. Their brains are forming, they have ideas which are out of the box. I learn a lot from the way children think. And quite frankly, you know, they’d be a source of material for me (laughs). They often have really, really interesting ways of looking, perspectives that I would never have thought of in my fossilised brain, you know. So I like the openness of children. And of course, I’d love to make things with them.

For young artists or creative practitioners finding their way through the world, what is the one thing you would tell them to avoid, either in terms of their practice or their approach to their work?

Being afraid. Conviction in your work, in yourself, and being fearless are things that you should always keep in mind. People will give you a lot of advice. People will have a lot to say about things, but the ability to make is special. Believe, hold on. I am a big supporter of making things by hand, going back instead of forward. And I think, perhaps, something handmade is invaluable and even more relevant in a digital landscape where everything is generated and, you know, keywords are typed in to make something. Hold on to your hands and don’t be afraid.

I think worry, anxiety, fear stops a lot of people from doing what they want to do. Don't let anyone bring you down. Of course, have self-awareness. I’m not saying be fearless at the cost of losing yourself or hubris, but if you have an idea and you like it, pursue it with love and do it at the cost of everything else. Don’t listen to anybody else. Listen to yourself.

The Setup / Mrinalini Sen

“I use clutch pencils, just for the convenience of not having to sharpen traditional pencils, and I use regular non-dust erasers, which I think are really good. When it comes to my linocut, I use Essdee linoleum and Pfeil cutters and carving tools. I use Sakura micron pens for drawing, which seem to be fairly standard. Actually, when I’m working on a draft or a concept, which is the larger part of getting to a final image, I don’t really fuss over what pens I use, as long as they’re fine-point. I prefer a fine point over a broad point.”