George Mathen is a visual artist and comics creator currently residing in Bangalore. He is perhaps best known as Appupen, the creator of groundbreaking graphic novels such as Moonward and Legends of Halahala. His third graphic novel, Aspyrus was released last year as well—all three books are set in the mysterious, mythical world of Halahala (created by him). George also plays the drums, and has been a part of Lounge Piranha, one of the best and most popular bands to have come out of Bangalore.

Read on for excerpts from a conversation with this former captain of the under-13 Kerala state cricket team about growing up in Kerala, pursuing theatre in school, running away to Bombay, the various bands he has been a part of, his brush with Bollywood, and what's next in store for the Halahala universe.

Why take on the moniker of Appupen for yourself?

‘Appupen’ means ‘old man’. In many ways, it is connected to stories. When you’re told stories as a kid, there’s always this appupen and ammuma who tell the story. I’m also called Appu at home, and Appu’s pen name is Appupen (smiles). Basically, I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do. I wanted to find something to keep my mind occupied, even when I’m old and can’t run around. I would still need to do this thing. I’ll probably end up alone, I think, but I would still need to have something that I’m passionate about. That passion always needs to be there. So it’s also like a joke in my head, that I will only become Appupen by the time I’m an old man (laughs).

What was the first comic book you read?

Actually, I wouldn’t have read it, since I was only around 3-4 years old. I would have just looked through it, and one of my grandparents would have been telling me the story. There were a few Tintins, I remember a Hulk as well. It was a very strange comic. Hulk is in the middle of nowhere, going through space, and there’s this tree with fingers pointing in every direction that comes to him.

(Laughs) Seriously?

Yeah. There are influences from that book in Moonward, as well. I don’t know where that Hulk comic is now, or which issue it was. And you know, those ‘80s comics had that different kind of printing, which I liked. When the glossy comics started coming out, I went off them. I also used to read Amar Chitra Katha comics, which I still have. I lost my collection of Tintins and a few other comics, but those are the only books I’ve lost. Everything I’ve owned after that is here with me (smiles).

Were you born in Kerala?

Yes, I was born in central Kerala.

What was the neighbourhood like where you grew up?

It was very nice. I was given this illusion of a perfect childhood, which worked. Even the illusion works there. As a child you want to feel secure; it doesn’t matter if it’s an illusion. You react to it later, that’s okay. But I had a really nice childhood. I was very happy. There was a lot of nature around where I lived, and a lot of fishing and floods and things like that; paddy fields behind the houses, etc.

“I was given this illusion of a perfect childhood, which worked.”

What school did you go to?

At the time it was called Corpus Christi High School. Now it’s called Pallikoodam. Kerala has a tendency to be too academically oriented, but my school wasn’t like that. The school was run by this superb woman called Mary Roy. I thought she was very cool, and she has been very influential for me. She was a very strong woman who stood up to all the Mallu men and fought for Christian women’s rights.

Sounds like a great mentor.

Yeah. She’s also Arundhati Roy’s mother. Quite a character.

Were you a good student?

Um… I used to study, but it wasn’t the main thing for me. I used to be involved in a lot of theatre and other extracurricular activities.

Growing up, were you always artistically inclined? Did you draw a lot? Did you write your own stories?

I used to write my own stories, but I was really into theatre. I was into theatre a lot more than I was into drawing. My school was very pro-theatre, and we were very active. I also used to play music in school. Drawing was actually not my strong point at the time. I haven’t been trained in drawing, and I used to try to make up for it with extra detailing in whatever I drew (smiles). I used to try to copy original art from albums and things like that. Then I started to make mixtapes and draw covers for them. I’ve given away most of them, but still have a couple with me that I can show you. My enthusiasm for drawing or art only came when I moved to Bombay for college.

Are there any memories that have stuck with you from your experiences with theatre in school? Acting in plays, or preparing for plays?

Hmm. We used to do at least two street plays every year. One of them used to be a nature-based thing… wherever there was a tree being cut, we used to hold hands and stand around the tree. We also had snare drums that we used to play and call out to people from nearby bus stops and do plays for them. There were a couple of other bigger plays that we used to do. One was Shakuntalam, and the other was Antigone. Shakuntalam is a dance ballet. If you’re familiar with the play, you know that a traditional folk ballet troupe travels around Kerala doing this play. They’ve set the style, and we had a couple of very well-known people from the troupe come and direct the play for us. One of them was this 84-year-old Kathakali dance director, who died a few years later. I wasn’t very serious about the play in the beginning. I was playing the fool, playing around behind his back, because I thought that he was 84 years old and I could get away with anything. But he was too cool for me. After just three days, he managed to convert me to his ways. He didn’t even have to pay any attention towards me, it was just watching him at work that did it for me—how well and how seriously he was doing everything. You couldn’t fuck with that. It was just so pure. I think it was one of the first times that I really understood what art was, and I couldn’t help but respect it.

You mentioned that you moved to Bombay for college. Why Bombay?

(Laughs) It wasn’t a planned move or anything.

Did your father have anything to do with the decision?

My dad was an alcoholic. He got out of a really bad bout of liver problems recently, but for a long time, it seemed as though he never knew what to do with his life. There was a lot of ancestral wealth, which he just sold off. He was on that trip. I never really saw him do much, except that he had a thing for cricket. But then again, he never played cricket, he tried to make me play it. I was never really very athletic, but I was sort of forced into it. If he'd told me to go to Bombay, I wouldn’t have gone (laughs).

“It was one of the first times that I really understood what art was, and I couldn’t help but respect it.”

What did he expect you to do?

He actually told me to go to Chennai. We had a lot of relatives in Chennai, plus both my dad and granddad had attended Madras Christian College—it was his attempt to make me go there as well. That would be really weird, if you think about it… three generations of students all going to the same college. And the M.C.C. has a certain reputation. Anyway, I was studying economics in 12th grade, and there’s a sort of rule in Kerala that if you’re studying economics, then you have to go to St. Stephen’s in Delhi. Nobody knows why. It’s just in everyone’s head as the place to go to.

(Laughs)

Yeah. I also had to try to get in, but I didn’t get in. I was waitlisted, and for a while, they kept dangling that before me. I felt like it wasn’t going to happen, and the college in Chennai just gave me admission without even looking at my marksheet. They were more interested in my cricket certificate—I was the captain of the under-13 Kerala state cricket team.

Oh, wow.

Yeah. Kerala state lost all their matches except the one against Goa (laughs).

(Laughs)

I thought the whole idea of me being the third person from my family to go there was ridiculous. I wasn’t cool with it. So I took off on my own from Chennai. I didn’t even book a ticket beforehand, I just went on an unreserved ticket to Bombay.

You didn’t tell anyone that you were going?

No, no one knew. I was staying at a relative’s place when I was waiting for my admission in Chennai. I was supposed to go back to Kerala, but I took a train and came all the way to Bombay. The morning I reached Bombay, I was talking to this guy on the train, and he said I should go to St. Xavier’s College.

(Laughs)

(Laughs) Yeah. And I got off at V.T., which was very close to the college anyway, so I walked there from the station. It turned out that I had missed the deadline to apply for admission. But I ran into one of my seniors from school there. He was a really good student, and he managed to talk someone in the college office into giving me an admission form. And in the next two days, I got into the college. After that, I called my dad. At the time, everyone in Kerala had this notion of Bombay as this place where the underworld resides, because of what was shown in films. Even in Malayali films, whenever anyone used to go to Bombay, they used to get shot (laughs).

(Laughs) How did he react to your calling him from Bombay?

He was okay about it. I think he was on his own trip at the time. But I think it was a good decision to have gone to Bombay. I needed that kind of atmosphere.

Did you enjoy your stint at St. Xavier’s?

I had a very nice time. I stayed in the hostel there for all three years, and I was also working on the side.

What were you working as?

My first job was as a tattoo artist.

Nice. Were you drawing regularly by this point?

Yeah. My hand was not really there, but my eyes were good at picking up details and styles. I had to train my hand a little more, but I was slowly getting more confident. Even by the time I was working on Moonward, I never thought that I could complete a story. Repeating characters and making them easy to recognise felt like such a daunting task. That’s why I exaggerated a lot of features in the beginning. But yeah, there was tattooing, and after that there was event management, and painting banners for shops. After a while I even organised an event on my own at a shoe shop called Kittens at Kemp’s Corner. I made a mascot for the shop and I got my friends together and made them dress up as kittens, and it went well for a while. I was getting paid by the shop. After a while, one of the shop’s competitors complained to the police, and one of the poor kittens got arrested (laughs).

Did you get into trouble as well?

I didn’t. The shop owner didn’t have some required permissions, but he sorted it out. He owned a bunch of shops, including Catwalk shoes.

Clearly the guy had a thing for cats and shoes.

(Laughs) I think Catwalk came first, and then he thought of the kittens.

Did you pursue any theatre at St. Xavier’s?

Actually, no. The theatre scene at St. Xavier’s was very different from what I was used to, and somehow I couldn't connect with it. I was friends with the people who were part of it, though. Quasar [Padamsee] was a good friend of mine.

Were you guys in the same batch?

He one a year senior to me. We used to play together in the St. Xavier’s cricket team.

You were still playing cricket, then. Were you a batsman or a bowler?

I was primarily a batsman, and a lazy fielder. That was my speciality (laughs). Quasar was the captain of the team. But yeah, I couldn’t really connect to the kind of theatre they were doing. I sometimes regret that I wasn’t a part of it then, but maybe I’ll get back to it at some point.

You’re a musician as well. How did you begin playing the drums?

I’ve been playing the drums since school. I had a cousin who used to play drums and the violin—he was a good musician. But then he got married, and so the family conspired and decided that the drum kit would have to be taken away from him, and somehow it landed up in my place (laughs). But even before that, I was learning to play the drums. Also, Sunil Chandy, who was responsible for forming Thermal and a Quarter, was my neighbour. His dad was a priest, and he had taught music to everyone in my town who could play music (laughs). Chandy used to sit on his terrace and play music, and he used to suggest music that I should listen to. He told me to check out Soundgarden, Dream Theatre, stuff like that. He was quite influential in my early years.

Were you a part of any bands in Bombay?

I didn’t play with too many bands, but one day, suddenly, I was invited to play with this band called Dead Sea Scrolls.

That’s one of those bands that everyone likes to mention when they talk about the rock scene in Bombay back in the day. Not too many people remember their music, but everyone has their own stories about Dead Sea Scrolls.

(Laughs) Yeah. I think they themselves cooked up the stories and spread them around (laughs). This guy Valmik Deshpande, who was in the band, came to me and asked me to play with them, and he was pretty desperate at the time. Funny story: a few years ago, I was at Hill Road in Bandra, somewhere near Hawaiian Shack, and I came across this toy store called Avenger Toys. I walked in to ask whether they would sell copies of Moonward, and it turned out that the drummer I replaced for Dead Sea Scrolls was the guy running the shop (laughs). I had replaced him for this video shoot that the band did for M.T.V. I think the song was called ‘Wish I Could Fly’, and we shot a video on this beach at Madh Island. Everyone in Kerala got a shock when they saw me on M.T.V. (laughs). And I never saw the guys from the band after that.

Why was that?

I think the band was already dying at that point, and they just wanted to see if the M.T.V. video could start something again. But nothing happened with the band after that. I was actually attending a workshop for 3D animation and graphic design at the time, which is where I'd met Valmik, who was also a 3D animator.

He was the singer?

Yeah, the singer and the guitarist and the songwriter and the guy who named the band Dead Sea Scrolls (laughs).

You had a brief stint with Metakix as well, right?

A little after that, yeah. Zombie (Metakix frontman) approached me and said that he needed a drummer for his band Metakix. We practised for about six months together and we had one gig at Razz Rhino. After that a few of my friends told me that I should probably look at playing with other bands (laughs).

Were you in any other bands in college?

Yeah, during my second year of college, I was a part of Mr. John’s Banned, with Garreth D’Mello. He’s a great guy. Garreth and I jammed together a few times after college as well, before I moved out of Bombay.

When did you move to Bangalore?

I was doing some freelance work for Greenpeace when I was in Bombay, and they said that if I wanted to be a proper employee, then I would have to move to Bangalore. I moved to Bangalore, but I didn’t really like working at the office much.

How and when did Lounge Piranha happen?

When I moved to Bangalore, I was looking for bands to play with. For a while, I even started a band with Sunil Chandy, who was in Bangalore at the time, called Soup of the Day. It was a nice band. We played a few gigs, and then Sunil moved to the U.K. I also played with another band called Old Jungle Saying.

With Sandeep Madhavan?

Yeah. Sandeep and I used to jam a lot. I met Abhijeet [Tambe] through Archana, a friend of mine. We jammed a lot together, and then we met Kamal [Singh] at a gig, who later joined us as well. That’s how Lounge Piranha started.

At the time, Bangalore was very well-known for its metal scene. Lounge Piranha was one of the few good bands from Bangalore, besides Thermal and a Quarter and Zebediah Plush, that wasn’t playing metal.

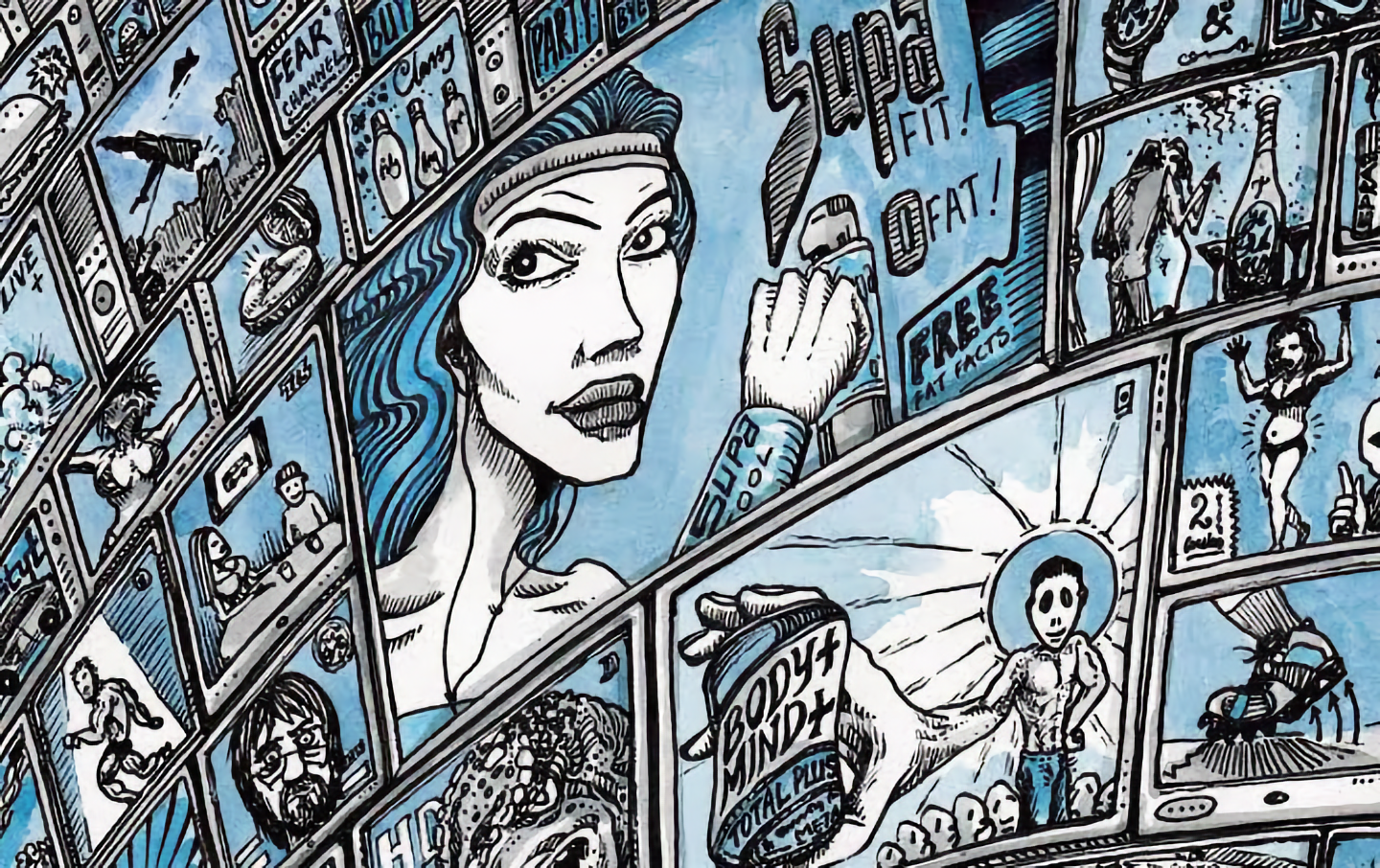

(Laughs) Yeah. We never really thought about that, though. A lot of the bands I was in earlier were flash-in-the-pan affairs, so with Lounge Piranha, I wanted to stick around with one band and see what could come out of it. I took that approach, and also looked at the band as a sort of brand: I did all the artwork for the band, I designed the website.

“For any band, the album artwork is extremely important. It is the visual counterpart to the music.”

I remember, yeah. You also had a long-running comic strip on the website. No one else was doing stuff like that at the time.

Yeah, it went on until I kinda lost steam (laughs). I have a couple of comic strips from that series that I didn’t put up on the website, but there’s no point in putting them up now (laughs).

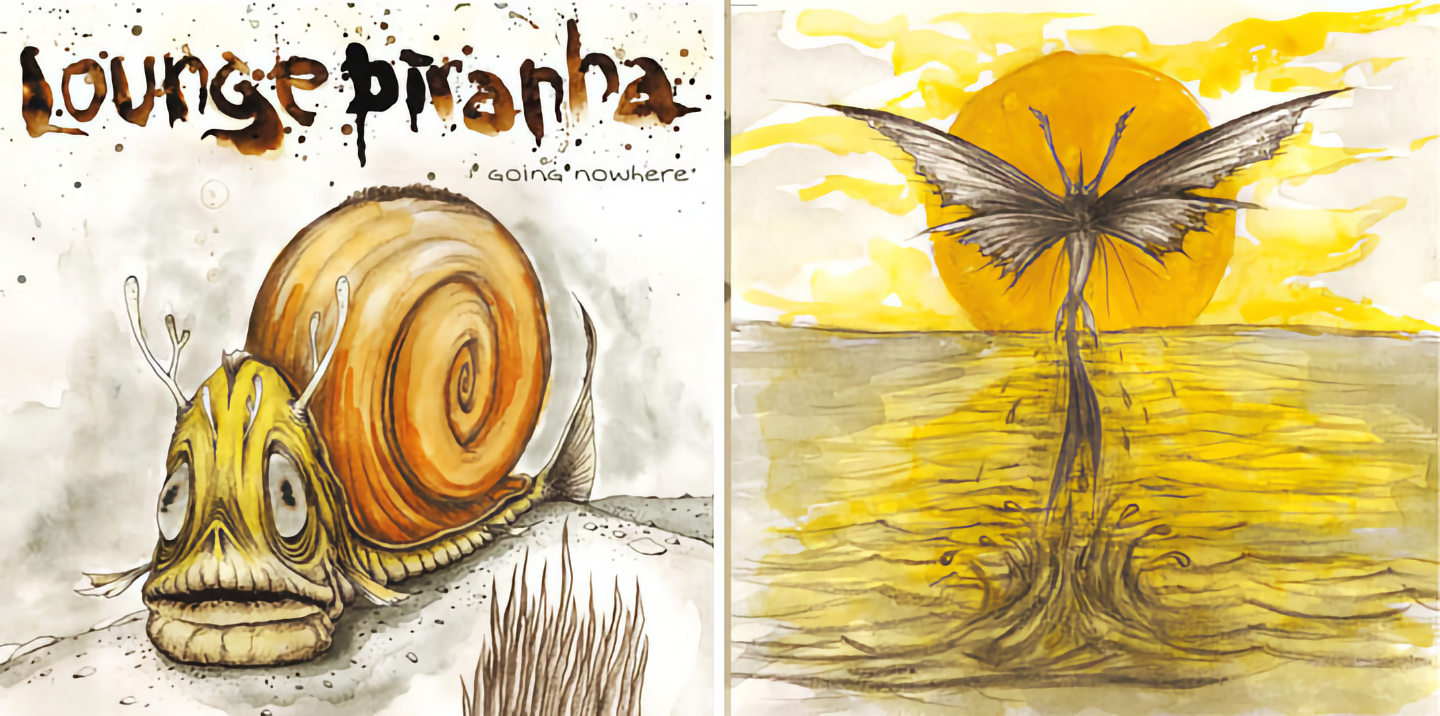

You guys released one album, called Going Nowhere. It’s been a while since the album was released, but the artwork you created for that is still considered as some of the best artwork created for an Indian band.

(Smiles) Yeah, yeah. For any band, the album artwork is extremely important. All of the bands I like have drawn me in with their artwork. Even things like drawing the Metallica and Slayer logos in school… the Iron Maiden logo typography, Judas Priest. And then there were the ‘70s bands and their album artwork. Yes, the Grateful Dead, bands like that. The album art is the visual counterpart to the music. You’re creating a world, and even with Lounge Piranha, I was creating a world for the music with my art.

Each song had its own artwork.

Each song had its own mood, its own character. We had a different illustration for each song, and we didn’t want to put all the lyrics in the inlay. Abhi and Kamal were also great about it, they left the artwork to me, and gave me great feedback.

The band was only together for a couple of years after the album came out, right?

Yeah. We actually had material for another album already sorted. We could have gone in to record it, we were thinking of recording it. But there was no second album. Abhijeet and Kamal started a t-shirt company together, and things didn’t go so well. After that, as a band, we stopped hanging out as much and having a good time, and basically, it doesn’t really work if you’re not having fun. I wish it wasn’t such a predictable story (smiles). We were around for long enough to just reap the benefits of being around for that long. I thought it wasn’t the right time to split up.

All the artwork that you created for Lounge Piranha, the comic strip and the illustrations for the album: did that lead you on to create your own comics?

No, I was creating my own comics at the same time as well. Actually, that’s why I decided to also create a comic for Lounge Piranha, because I was also creating my own comics. But the Piranha stuff was definitely practice—if you look at it now, a lot of it is very rough.

Did you have the idea for the world of Halahala in your head for a long time?

Yeah, since 2004. I hadn’t named it Halahala at the time, but the stories were already there in my head. When you’re coming up with stuff, in the beginning, there’s a lot of stuff that you just reject, right? It’s very intense—you think you’ve cracked it, you think that ‘this is it’, and you’re going forward with it, but a lot of it is just the background. It’s not really the story or the plot, but you’re just so caught up with the background because you want that to work. It’s basically your escape—you want to escape into that world and figure out how it works. It’s a very exciting part of the process, but you need to know when to stop and how much of it to chuck. So there was a lot of chucking happening at that point.

Were you drawing out parts of the world, or were you just writing at this stage?

I was only drawing premises, settings, but I was writing more. I was also a little lost at the time, because I wasn’t sure whether comics was something that I could pull off. At that point, I had done some 3D animation and some film work when I was in Bombay. I couldn’t really leave Bombay without tasting some Bollywood, right? (Laughs)

(Laughs)

I just wanted to see how things were made. I could see that it was set up in such a way that nothing original could come out of it. I was doing some set design for a few films at the time. There was one film that was being directed by Tanuja Chandra, who was a decent director, and produced by Mukesh Bhatt. They were producing five films at the same time, and they had five different locations in which they could shoot. So they were just moving the films around across those five locations. And each of the movies had to have five songs. One song was the intro of the hero, one song was the intro of the heroine. One song was the intro of the movie, one song was a sad song. And the last song was a toss-up between either a masala song or some anthem or heroic kind of song. It was a conveyor belt format. The same dancers were also hired for all five movies (laughs). And I thought the set design would be important for the films, but I soon saw that it didn’t matter at all (laughs).

How did those experiences of working in film influence the comics you were working on?

I had some ideas, but if I wanted to make animated films, I would need a huge budget and a lot of people working on them. The only thing I had was time, and my own skills. That’s what I’ve come to love about the comic format—that you can do it by yourself. It’s one place where your ideas can get realised pretty much the way you want, if you have good skills. You don’t need a cameraman, or a music director, or another editor, or any actors, etc. In film and other mediums, the original idea can get diluted due to many people putting in their ideas as well.

I was still figuring out my story, and the medium of comics was perfect for me. Of course, I had to get better at writing and drawing, but it would happen along the way. I had some good stories, and wanted to spend some time on them and convince myself that I could pull them off. I didn’t expect to build a world in just a couple of years, but it would be my work, and I wanted to see how far I could take it.

When did you first consider taking your comics to publishers?

I didn’t think publishing would happen. I was just creating comics to see if I could do it. When Blaft decided to publish my first book Moonward it came as a surprise. I had put up some comics on my website, and they liked them and called me. It was the only way it could have happened, because I was not going to take my comics to a publisher and pitch them any ideas.

“That’s what I’ve come to love about the comic format—that you can do it by yourself. It’s one place where your ideas can get realised pretty much the way you want.”

Do you think of all three of your books as a series? Or are they just collections of stories that are all set in the same world?

Hmm. The only connection is the world [of Halahala], really. There are many characters, machines, and cities repeating through the stories that are set in this world, but I haven’t made that very obvious. There are some things I leave in there for the readers to pick up on. I have this larger idea of connecting it all together, the Halahala mythology, and I have some cement in place for that, but that will still take a lot of work.

What Halahala books are you working on next?

I’m working on a book called the White City, and I’m also working on a book called Heroes of Halahala with Rahul Chacko. Heroes will be very similar in treatment to Legends of Halahala, sort of like a Legends 2 or 3. It’ll be Halahala’s take on superheroes. I don’t know which of the two books will come out first. I’m also working on some animation and some audio-visual elements to bring out the stories. When it’s too quiet, that puts some people off (laughs).

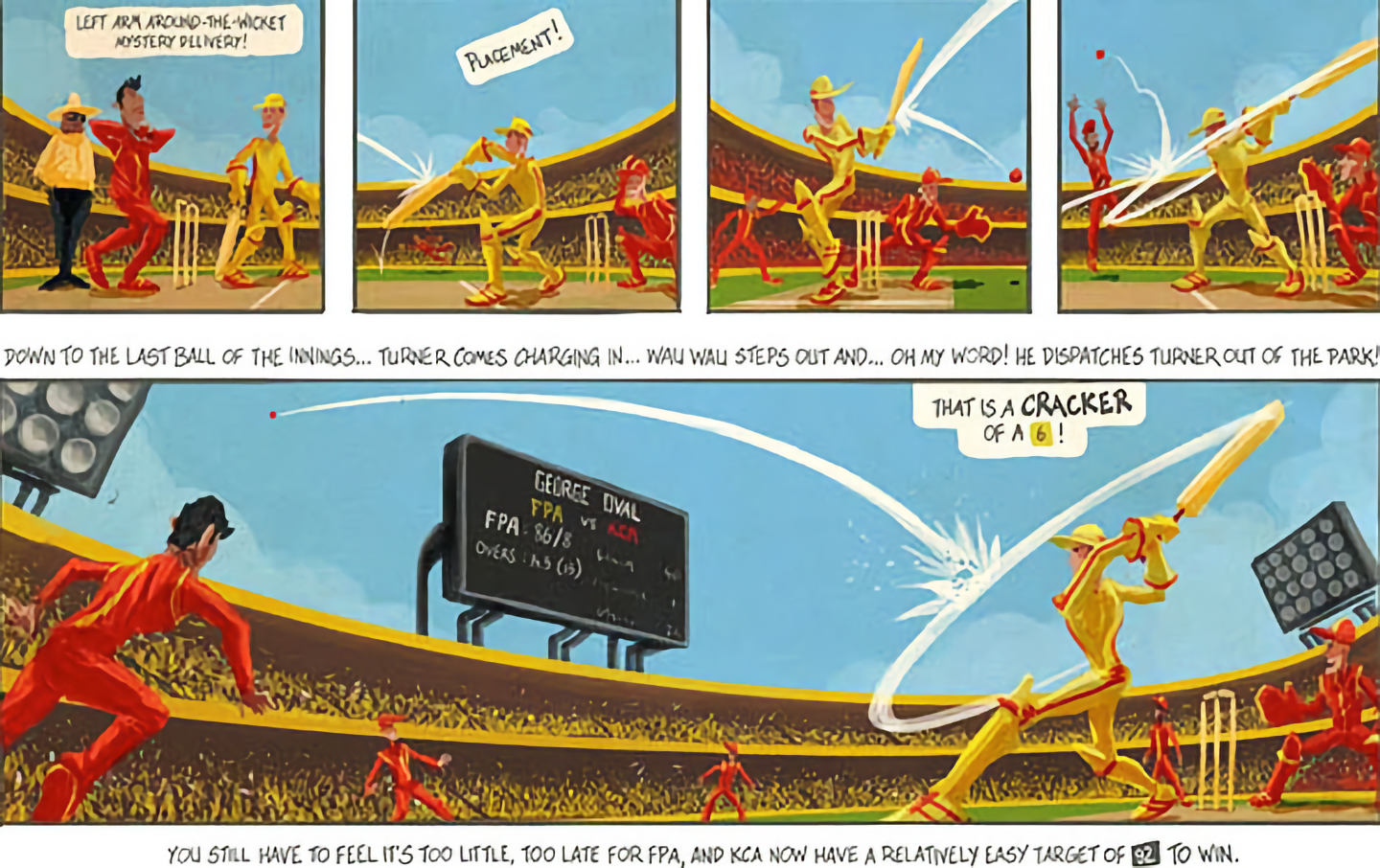

Is your collaboration with Rahul Chacko your first time working with someone else on a book?

Yeah. We’ve also been doing a comic strip together for ESPN Cricinfo for the past few months. We work on the stories together. I do the pencil and pen work, and then he works on it, improves it, and adds some depth and colour to the pieces. His work adds an extra dimension to the artwork, so it’s good. I think the comic strips have come out better than if either of us had created them individually, which is the whole point of a collaboration.

In recent years, there have been more and more people creating original comics in India. Do you see yourself as part of a comics community or movement in the country?

No. I sort of feel very isolated as a creator. So far I’ve only managed to work with Chacko (laughs). Even in the comics scene, I’m always grouped together with Amruta Patil or Sarnath Banerjee or somebody whose work is worlds apart from what I’m doing. Each of us is in our own zones. Just because we draw pictures and write words, they put us together in some panel, and most of the time we can’t even reach any common ground. All of us approach comics from different places. It’s almost like saying everyone who plays the guitar belongs to the same genre of music (laughs). I’d like to contribute to the scene, but I don’t see it as a movement, I see it as a vacuum.

Besides the Halahala books, what else would you like to work on in the near future?

What I have always liked about comics is that I can create them myself. But another very important aspect of comics is wit and making fun of things and questioning things. These days, we don’t have anything that makes fun of things. Even whatever ads come out on T.V., everyone takes them so seriously, like the word of God (laughs). I feel that we don’t see comics for what they are. Somewhere, comics have become all about the celebrity creators, and maybe the people who are making comics are also aiming at it in that kind of way. What I can see is totally missing is that cheap comic you can buy that has good stuff and is completely irreverent, something with balls. One thing I would really like to do is to start a rag like that.

The Setup / George Mathen

"I use a desktop computer and Adobe Photoshop for cleanups. I like to stick paper over screwed up parts of the page and make corrections, but you need to clean up the edges of the new paper after scanning. I use Adobe InDesign for making and designing the books. The less you leave for others to do, the surer you can be, huh?"

"The tools are as basic as can be. Pens, pencils, water colours. I'm not very picky about the tools, though once I'm comfortable with a few things, I like to stick to them. I've used digital colours for a few stories, where I think it would add to the feel/ mood of the story, like Oberian Dysphoria in Legends of Halahala. I draw on A3-size cartridge paper, usually. I don't think I've really found the right tools yet, though. I've found a good mix of easily available (and not too expensive) tools. It's no point if I get great tools that run out halfway through my story, and I have to wait for the next shipment."