"All the nights I spent without any food in my stomach kept me awake and wondering if I have any stories to tell,” says Devashish Makhija, a filmmaker, writer, graphic artist, and poet based in Mumbai, about his early years in the city. “A lot of kids now don’t get that opportunity. It’s a lot easier to get into the industry these days, but I sometimes wonder whether it’s too easy."

Makhija has worked on films such as Black Friday and Bunty Aur Babli, and his own film Oonga (starring Nandita Das) premiered at the New York Indian Film Festival in 2013. He has written two bestselling children’s books and is a prolific writer of short stories. Forgetting, an anthology of short stories written by him, will be released by HarperCollins India in December 2014.

Read on for excerpts from a conversation with this former national karate champion about growing up in Calcutta, working in advertising, his early struggles as a filmmaker in Bombay, working with Anurag Kashyap and Manoj Bajpai, the making of Oonga, and that one terrifying night in December 1992 that still casts a shadow over his life today.

Where did you grow up?

I was born and brought up in Calcutta. I lived there for the first 24 years of my life. I used to live in this area called Park Circus, which used to be around the fringes of Calcutta, but ever since Salt Lake turned into this full-on satellite city, Park Circus sort of became the heart of Calcutta. But I grew up in the fringes of old Calcutta, when it was still worth living in.

What do you remember the most about your neighbourhood?

Interestingly, I have very, very specific memories, a lot of which I still write about. My family lived in a building that was the only building in a Bangladeshi refugee area. It was just one building with six families, in the middle of a sprawling slum full of Bangladeshi refugees, who had probably moved there a few years before I was born. I spent all my childhood surrounded by a strange, amorphous sense of history. I never really had a sense of my own roots.

Did you have many friends among the refugees?

Yeah, the refugees were our support system. They were the only people we used to interact with on a daily basis. But there were also gangsters there. It was very similar to what areas like Nagpada and Behrampada are in Bombay. A lot of crime festered there—not any more, but back then, yes. My father had to pay hafta to some of them. They even blew up our scooter once, with handmade bombs, because we didn’t pay them. There also used to be sword fights; I’ve seen a guy get hacked to pieces right below my balcony.

In daylight?

In the night, but in broad night-light (smiles). Right in the middle of the street. Well, it wasn’t really a street then, but it is now. The slums have all been replaced by buildings.

Did it scare you to live in that sort of neighbourhood, or did you just sort of accept it as the way things were?

Yes, I was scared. Interestingly, my new book of short stories is going to be out soon from HarperCollins, and some of the stories are about this phase of my life. I haven’t been able to exorcise it. Those people were… when I say ‘those people’, I don’t mean it as ‘us and them’, but just the fact that they were Bangladeshis, and we were Pakistanis, because we were Sindhis and also came from across the border (smiles). I used to go to their shops to buy groceries, I used to go for karate lessons with their kids, my dad’s scooter was repaired by one of them, but when it came to bullying us into giving them hafta, no one really protected us. There was an interdependence but there was also fear. In fact, the first film I ever wrote, which I haven’t been able to find financing for yet, was about the night of December 6, 1992.

What happened on the night of December 6, 1992?

I was 15 then. This was around the time of the Babri Masjid incident, and there were ripple effects in Calcutta as well. We were living in a Hindu building, and the entire slum was full of Muslims. That night, something happened, and they attacked us. We almost got killed.

What happened, exactly?

They propped up a ladder against the building, and they climbed up with swords. They were going to finish us off that night. In fact, that afternoon, my mum packed my sister off to a far-off relative’s house. My father had gone looking for help and he couldn’t get back in time, because they suddenly called a curfew. So it was just my mum and me. At night, they were climbing up the ladder to come and attack us—it was one of those long bamboo ladders that are used to repair the street lights—when at the last minute, an Air Force patrol Jeep that was doing the rounds entered the lane, which made the refugees run back to the slums. After that, there was an enforced curfew until morning. Strangely, by morning, things were weird, but it was… over. And things never went down that road again.

“I kept thinking about all the things that they might do to my mother, and how I would at least take one of them down with me.”

Just like that?

You know, that night, I kept imagining scenarios. I was so scared that I pissed my pants multiple times. All of us had gathered on the terrace, and I kept thinking about all the things that they might do to my mother, and how I would at least take one of them down with me. My thoughts had reached that sort of an extreme. I remember thinking about what really starts this kind of riot. All those people who were about to attack us were familiar faces. We used to have daily exchanges with them—everything from business transactions to talking about the weather. And the same people were now attacking us. Something happened that night. I think that when you become part of a mob, the entire mob has one consciousness. Your individual consciousness takes a back seat. And once the mob disperses, you go like, ‘what the fuck did I just do?’ But that night, I didn’t really understand it. It scarred me for life. I even wrote a film around that one night.

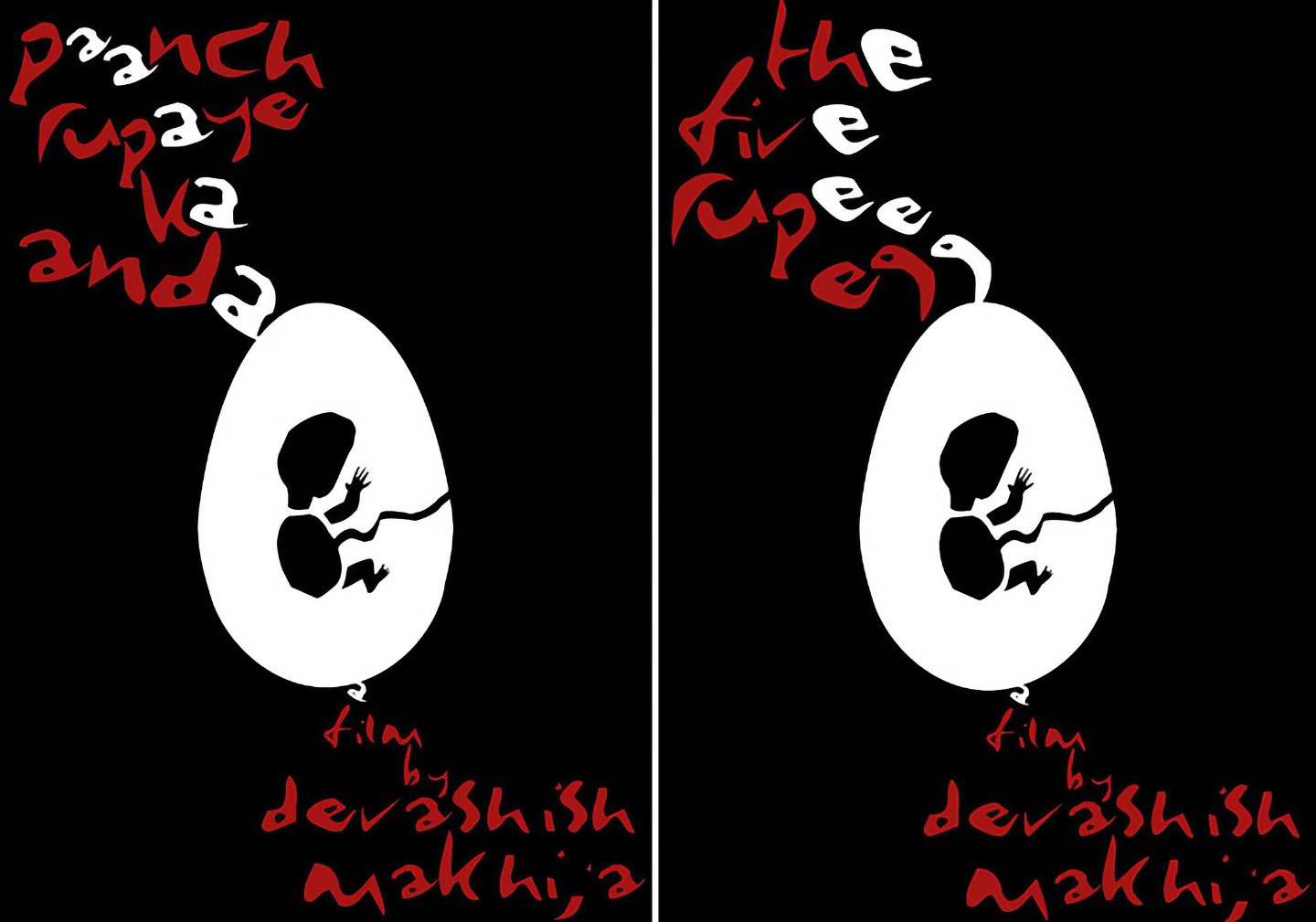

What is the film called?

It’s called Paanch Rupaye Ka Anda. Back then, an egg used to cost 60 paise. In the film, the grocer in the area has only ten eggs left, and since there is a curfew in place, no new eggs are going to come in. Those 10 eggs can now be sold at a premium. The grocer decides to charge us ₹5 for each egg. But being a Hindu, he is a little scared of the Muslims from the slums. He doesn’t have the courage to sell them eggs for ₹5, so sells each egg to them for 60 paise. And you can see how a ₹5 egg can start a riot.

Did things in the neighbourhood go back to normal after that night?

It was weird. There was a strange tension. Even they knew that something strange happened that night. It took a few months for things to go back to normal, and I guess some people have forgotten it, but I never could.

Did you go to school in the same area as well?

Yes, in the same area. I went to Don Bosco High School.

Were you a good student in school?

Embarrassingly, I was a good student. I was a bit of a geek. But I used to study last-minute, and I was almost never in class as I used to be involved in a lot of extra-curricular activities. I was a national karate champion, I was in the school band and the dance team, I was into creative writing and debating. I used to read a hell of a lot. I think I was in the top 20 in the I.C.S.E. board exams that year (nationwide).

Nice. Did you go to college in Calcutta as well?

Yes, I went to St. Xavier’s College, but don’t ask me how I did in college (smiles). I didn’t do too well; I lost interest in studies. Strangely enough, I studied economics. I still don’t know why. I also applied to the National Institute of Design to pursue a design course, but didn’t get through.

What was your first job after college?

I interned for a bit at an advertising agency through my college years, and then joined McCann-Erickson after college.

When did you think of writing for films?

It came about as a reaction to advertising. I hated advertising. There’s an initial high of coming up with tight ideas, you know? One-page ads, 30-second T.V.C.’s, and then it hits you that all you’re doing is plugging a black-coloured fizzy drink that nobody should be drinking in the first place. All of that was giving me sleepless nights. I didn’t want my creativity to be used just to peddle products. I know it sounds like this big philosophical stand, but at the time I wasn’t able to come to terms with it. I felt artistic inside, but the work didn’t feel like art. I once won an award for a hoarding I did; the hoarding was up on the road, people would pass it every day, and no one knew that I had made that. If I’m an artist, people should know that I made that. I felt extremely disillusioned. Just then, a couple of my friends who had gotten through to N.I.D. got in touch and said that they were now in Bombay, and that I could live with them and pursue something in the city. I decided to take that chance.

“I hated advertising. There’s an initial high of coming up with tight ideas, and then it hits you that all you’re doing is plugging a black-coloured fizzy drink that nobody should be drinking in the first place.”

But why did you choose film writing?

I don’t know, really. I didn’t know what else to do. I had a band in college called The Big Lyres—I was interested in music. At the same time, I wanted to write, I wanted to make art, I wanted to do everything. I thought that the only thing that would allow me to do all these things was cinema.

What were your early days in Bombay like?

I was living in this tiny room in a slum rehab colony behind Film City with six other people. It was terrible; I didn’t think I’d last in the city. Every day I’d contemplate going back. I didn’t know anyone in the city, so I used to go with my friend Rajat Nagpal to design houses, and ask people for names and numbers. Then someone gave me this book called the Film Industry Index — which doesn’t exist any more, because people have moved on from landlines to cell phones — and the book listed every landline number of every filmmaker and film production house in the city. I kid you not, for five months, I stood at P.C.O.’s and made calls from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily. I made calls, waited outside offices, and begged people to meet me. I think everyone pays those dues when they come here, but I wasn’t emotionally prepared for it.

The colony that I lived in was called the Nagari Nivara Parishad. I’ll never forget that place. It was like a strugglers’ colony. Every person you met there was either a writer or actor or cinematographer, etc. who had come to make it in Bombay. It was just this large mass of insecurity.

How disheartening was it to live in that sort of environment?

Very. Especially when you’re an absolute beginner, and you haven’t figured out that things do get better. You’ve come from a totally different world, and this is a world that you haven’t even read about. You don’t know if there’s a tomorrow or a next level, or if any doors are going to open. You’re just hoping. And how much can you hope when you’re running out of money? There were nights when we didn’t have money to eat. We used to have Parle-G and dal for dinner. I used to think, ‘Is this going to lead to anything? Should I quit while I’m still sane?’ And then one miraculous thing happened for me.

“You don’t know if there’s a tomorrow or a next level, or if any doors are going to open. You’re just hoping. And how much can you hope when you’re running out of money?”

What was that?

Rajat met Anurag Kashyap and asked him if he’d meet me. I didn’t know who Anurag Kashyap was at the time. I was not a film buff. I didn’t know that there was a film called Satya and that he had written it. Rajat told me to meet him, and that maybe he would give me work. He told me that he was the guy who wrote Satya, and I was like, what the fuck is Satya? (Laughs)

(Laughs)

So I met Anurag, and he was the warmest, most welcoming guy I had met in the past six months—and I had met everybody. I had met Ram Gopal Varma, I had met Vinod Chopra, Rakeysh Mehra, everybody. I assisted him on a film that never took off. I worked on it for three months, and it didn’t go into production. The film got shelved, the financers backed out, the actors backed out, everyone went home, and I was still on my computer working on the location breakdown. Anurag came to me and said, ‘Boss, it’s not happening.’ I said, ‘No, no, it’ll happen sometime,’ because I had no concept of a film getting shelved. That’s when I realised that it can also happen that you start working on a film and it doesn’t get made. I was shattered.

How did you come to work with him on Black Friday?

He called me to his office one day, plonked some 10 kilos of papers on the desk, and asked if I would research something for him. And I spent the next six months doing research for what would become Black Friday. I drew up a sort of structure based on which Anurag wrote the film, and then I assisted him on the film as well. By then I had been in Bombay for about a year, and I was finally getting started.

Were you making a little money by then?

No, no (laughs). On Black Friday, I was making about ₹6,000 per month, all encompassed. In fact, that’s before T.D.S., so I used to make around ₹5,400. Money-wise it was really rough. I used to spend more than I made. But working on Black Friday was very satisfying. It was my film school. I learnt everything on that film.

What are some of the things you learnt while working on Black Friday that you wouldn’t have learnt otherwise?

The film’s producers didn’t have any money for research. If you had to get something from the Times of India archives, you had to pay a fee for each photograph, etc. Mid Day was producing it, and they didn’t know where the funds would come from. So I had to use jugaad. I took Rajat’s expired N.I.D. identity card, scratched out his face, and made it look really old. And I went everywhere as an N.I.D. student and got people to give me a lot of stuff for free (laughs). No film school can prepare you for the kind of jugaad that you need to do to make a film in Bombay.

What kept you going in those first couple of years in Bombay?

I don’t know. Desperation, maybe, and the fact that I had nothing to go back to. There were also emotional reasons—my mum had expired about six months before I left Calcutta. My father still lives alone in Calcutta. I feel guilty for having left him alone, but Calcutta was a dead city for me. There was nothing left for me there. I used to do a lot of graphic art and write poetry in those months, so that kept me going creatively. I didn’t have a computer, so I used to sit at night on Anurag’s computer creating artwork using Photoshop and Illustrator.

“No film school can prepare you for the kind of jugaad that you need to do to make a film in Bombay.”

What did you work on after Black Friday?

After Black Friday, I was the assistant director on Bunty Aur Babli, after which I was the chief assistant director on Jaane Tu… Ya Jaane Na. That was the film’s first schedule in 2005, which got shelved. After that, Jaideep Sahni and Aditya Chopra gave me my break. They asked me to write and direct an animation film for the erstwhile Yash Raj and Disney tie-up. They had tied up for two films, one of which was Roadside Romeo, which tanked very badly, and the other was my film. I was already in production for three years when Roadside Romeo tanked, after which they pulled the plug on the project, just one year before it was scheduled for release. Around that time and after it, I had a lot of shelved projects. I had a period of about four or five years when everything I touched didn’t get made. I wrote the biopic on M F Husain’s life, which Owais, his son, was going to direct. I wrote Anurag’s film Doga, which didn’t happen. I had about 14 shelved projects. Every time a film gets shelved, a small part of you dies. A film takes roughly six months to write, which is a lot of time. When you see six months suddenly becoming zip, zero, you start to ask yourself how you can sustain this.

Outside of films, you’ve written children’s books, poetry, and short stories. Did you start exploring other forms of writing during this time?

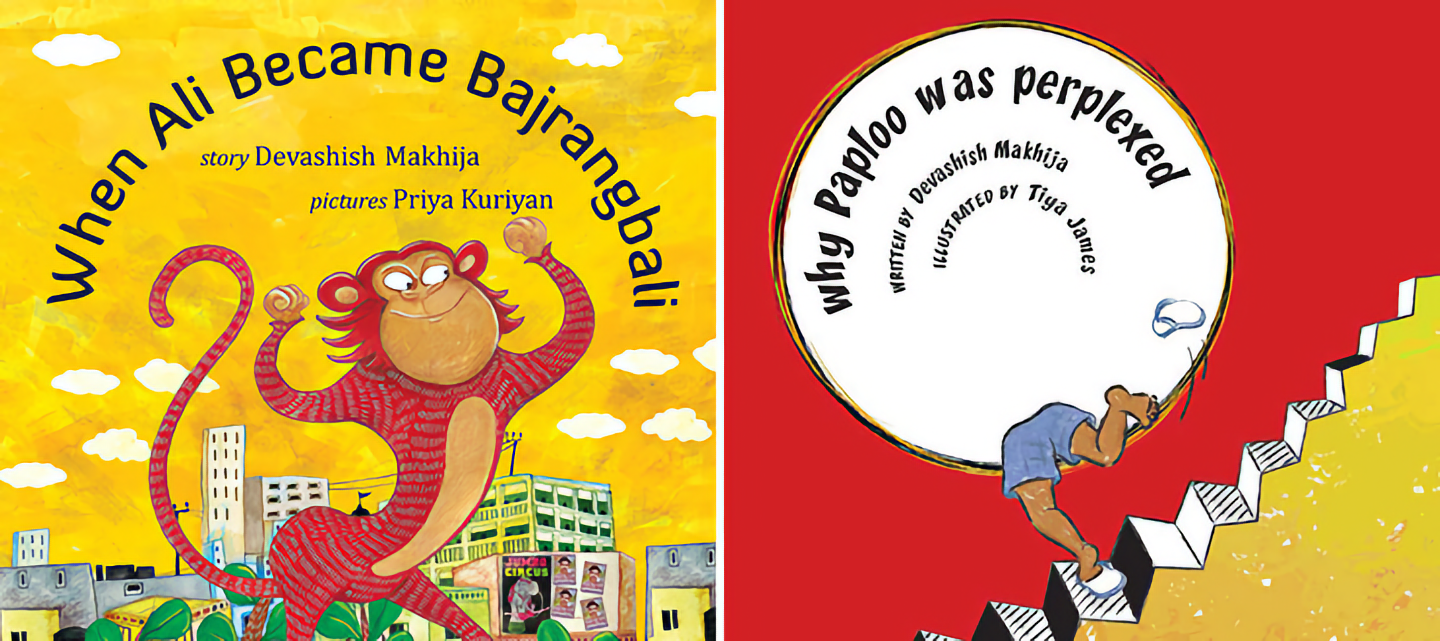

Yeah, I used to keep writing. While writing scripts, I used to get other ideas that I used to write as short stories. I wrote some other films that I knew would never get made because they were too dark. People don’t like to make dark films in this country, so I rewrote those as short stories. The children’s books were a reaction to my animation project getting shelved. For those three years, I had lived with animals, and I was thinking like animals. I had gotten into a Disney space. I toyed with some ideas in that space, and the children’s book I wrote (When Ali Became Bajrangbali) did rather well.

Every other creative avenue I’ve pursued has been because cinema has not worked out. When I look back I think I’ve been fortunate, maybe, because I have two bestselling children’s books, I have one solo art show, I have a compilation of poetry behind me, my book of short stories is coming out in December, and I’m halfway through my novel. None of this would have happened if my feature films had worked out (laughs).

When a film gets shelved, do you still hope that it will get made some day?

Always. Always. But that in itself is very exhausting. It’s like breaking up with someone and living with that slim hope that we might get back together some day, when we’re 50, 55, 70. It’s exhausting, man, because how many of these thin cords can you live with? You have to cut a few, but with films you can’t, because you never know when someone will revive a film project, or you may be able to use one idea somewhere else. And I hate wasting ideas.

Are you wary of other people taking your ideas and using them to make their own films?

All the time. And it’s happened to me. I won’t give you names, but I’ve had my ideas stolen by people who have been mentors to me.

How do you react to that?

That’s something I learnt from Anurag. When I wrote my first film, Paanch Rupaye Ka Anda, I used to take it around to people, and I asked him, what if they steal it? All he had to say was: come up with another one. What are you going to do? You can’t live in that insecurity and not put your film out there.

Is there nothing you can do to prevent it?

We have a film writers’ association, we register our work, but at the end of the day, when someone steals your work, they don’t steal it in its entirety. They steal the potent seed idea. How far are you going to go to prove that the seed idea was yours? Where do you begin? And sometimes the guys are big guys. How do you start that fight? You can take precautions, but there’s no point in being too careful. You have to operate in good faith.

“I won’t give you names, but I’ve had my ideas stolen by people who have been mentors to me.”

You’ve written and directed a half-Hindi, half-Oriya film called Oonga. Could you talk about the making of the film?

I’ve always been interested in politics. I’m worried all the time about this country going to the dogs. I keep reading, mostly about insurgencies. Maybe it’s got something to do with that night back in 1992. Exactly what is it that causes one side to turn against another? A few years ago, I wrote a film called Bhoomi for a cinematographer called Abhik Mukherjee, which never got finished. While working on that script, I read a lot about Naxalism and the Kashmir situation back then. I read about 7,000–8,000 pages of material, from government websites to underground books that didn’t get published. All that stayed with me.

In 2010, I journeyed to Chhatisgarh, south Orissa, and north Andhra with a journalist friend, with no particular agenda. There was so much shit going down there that I came back extremely disturbed and with so many ideas that I didn’t know what to do with them. I’ve seen 13-year-olds being thrown into jail while we were there; we tried to fight for them and got beaten up by the police. Lawyers shut their doors in our faces. I saw a guy getting shot. At the time, I had a three-film deal with Yash Raj, and they wanted me to make rom-coms. I walked out of the deal, because I couldn’t get myself to write rom-coms when the world was going to hell. At the time, a lot of the stories that I came up with were very dark, and I couldn’t find producers for any of my ideas. After a while, I realised that until I make it a lighter story, no one is even going to want to listen to what I have to say.

Is that where the idea for Oonga came from?

Yeah, I was brainstorming for ideas with my current flatmate Sarat, who co-wrote the film, and we cracked this idea of a little Adivasi boy who runs off to the city to see the film Avatar, because he’s heard so much about the film. And he notices that, hey, this is the exact same thing that’s happening to the Adivasis. I started fleshing it out, and met some first-time producers who loved the idea. However, they said that we needed to make it in record time, and with an extremely low budget. Otherwise it wouldn’t be viable, because no one really knows how to sell a half-Hindi, half-Oriya film. So I said sure, let’s get started.

How long did it take you to make the film?

We shot the entire 100-minute film in 18 days.

That’s mental.

Yeah, it was crazy. Our shortest day of shooting was 16 hours, and the longest was 22 hours. We had to finish making it.

Were the actors okay with the schedule?

It was rough. It wasn’t fair on the actors, but we had to do it. It was either that or not making the film at all. We had Nandita Das and Seema Biswas together for the first time in a film, and they had a very tough time. But they were fantastic in the way that they just committed to the job at hand. Lots of other things happened as well. We didn’t get permission to mention Avatar in the film, because Avatar 2 was in production. We wrote to Fox and they replied saying that not only would they not allow us to use the property, but if we made the film, they’d make sure that it wouldn’t be screened anywhere in the world. So we went back to the source material and changed Avatar to the Ramayana.

The film was screened at the 2013 New York Indian Film Festival. What was the response like?

It was emotional. I don’t mean to sound racist, but the white people there were weeping at the end of the film. A lot of people, when they look back at the past, now regret what their forefathers did. The film was also screened at the Mumbai Film Festival, and we got some insane reviews for it.

“I couldn’t get myself to write rom-coms when the world was going to hell.”

Are you looking to do a proper film release in India?

I don’t know, man. My producer’s been struggling. It’s half and half, right? Half of it is a subtitle experience, and the other half is in Hindi. So do you release it as an Oriya film or a Hindi film? There is no market for Oriya films, and Hindi film distributors are totally averse to a subtitle experience. I don’t mean to sound pessimistic, but I don’t think it will ever find a release. Oonga could easily have become my 15th shelved project, but at least this film got made (smiles).

What projects are you looking to work on in the near future?

Manoj Bajpai committed to a script that I had written in June, and he had dates available in August. The story is set against the backdrop of Ganesh Chaturthi in Bombay, so I had to shoot during Ganpati, in the rain. Again, it’s a slightly dark, political film set in 2007, when the Marathi migrant clash was happening in Bombay. In that scenario, one Maharashtrian policeman sort of stands up against these politics. Being a Bihari, Manoj Bajpai was very excited to play the role of a Marathi cop. However, the financing didn’t come through, since most producers don’t want to take the risk. Manoj is still standing by me, and I’ve already shot some footage, so the film will hopefully happen soon. I’m also in talks with Nawazuddin Siddiqui for another film, which is based on a short story I’ve written for an anthology called Mumbai Noir. And, of course, Paanch Rupaye Ka Anda.

The Setup / Devashish Makhija

"I used to romanticise writing on paper until I wrote When Ali Became Bajrangbali and realised the tragic irony inherent in writing a story about environmentalism on paper. I was part of the reason that trees were losing the battle to man, so I pretty much gave up writing on paper. Now I only use paper—the backs of used sheets from old drafts of printed screenplays—to draw thumbnails of any graphic art ideas I might be exploring.

"Sometimes I punch ideas into calendar notes in my old, decrepit cell phone when I'm on the move, to be transferred later. Mostly I write using Microsoft Word on my eight-year-old black MacBook—it's come to resemble a new-age Remington typewriter. Other than that I'm not hung up on 'tools', really. I'll use whatever's handy. It's more important to not lose the idea that flies into my head. I grab my friends' laptops sometimes to furiously type something and email it to myself.

"I shoot with whatever camera I can borrow from whoever's willing to lend it to me. I'm thankful for digital technology, although I'm a little primitive in my mastery of technology. It's allowed for less loss of information from brain to page, and helped me save a shit load of paper (and hopefully, a few trees and monkeys as well)."