"I often think about how I am privileged enough to be able to work on my personal projects, and to not have to do commercial work all the time," says 30-year-old illustrator Anand Radhakrishnan as we walk around his neighbourhood in Chembur, Mumbai, talking about his work. "Maybe it's not completely rational, but I have some weird kind of middle-class survivor's guilt, which plays into how I approach my personal work."

Though he prefers to work in 'pure' illustration—illustration for the sake of illustration, as he puts it—Anand has in the recent past been involved with a number of acclaimed comic book projects, including Black Mumba and Grafity's Wall. Read on for excerpts from a conversation with Anand about his early years, making the switch from medicine to illustration, the importance of discipline for a freelancer, being an outsider to the world of comics, his addiction to audiobooks, and why he doesn't like using the word 'style' in the context of visual art.

Let's start with the early years of Anand Radhakrishnan: where did you grow up?

I grew up in Andheri West [in Mumbai]. I did a bit of my schooling there, until fifth standard, and then we moved to Wadala, where I spent the next 15 years. I finished my schooling at St Joseph's School in Wadala. After my 12th, I had no clue about art and stuff, so I did a year of B.Sc. (laughs). I had no idea that art was a viable career choice.

Were you always interested in illustration?

I used to draw in school. I didn't know what 'illustration' was. I just knew that people draw, that art was kind of a career and that some people did that, but I wanted to be a doctor.

Oh, that's interesting.

Yeah. I gave the entrance exam as well, but I didn't do well at all. I was really bad at academic stuff (laughs). Well, I guess I did okay, I could have gotten into one of those colleges at the outskirts of Bombay, but by then I had realised that you can actually draw for a living as well. I did a year of B.Sc. at St. Xavier's College, but around the same time, I used to do walks around J J (Sir J J School of Art); I used to talk to the people there and try to get information about how to get in. Then I enrolled in this tuition class for the entrance test there, which is when I started to figure out how this illustration thing works. I gave my Intermediate art exam while I was still doing B.Sc., before I went for the entrance test at J J. I got in and went to art school, and from then on the progression was pretty linear.

What was art school like for you?

For me... see, I was always an outsider to the art world.

In what way did you view yourself as an outsider?

For me, it was all novel—I came from B.Sc. and science and cramming for exams. I never actually thought that I could draw for a living. It was a completely different experience for me. It was good, but I felt like J J didn't teach me anything. The assignments were okay, I guess, but J J has a curriculum that was maybe more apt for the '60s and '70s—maybe even older. I think they're trying to change it now. I didn't learn much there, but I used to look up stuff on the Internet. Cgunit was an online gallery at the time that used to post work from artists—it was a huge inspiration for me. Through that I came across the work of many international artists.

Did you feel different from the other students in any way?

J J is a government college, so it has a pretty nice mix of students from urban areas as well as those that come from rural parts of the country. Those guys are really skilled, and they are constantly working. They even take up freelance jobs on the side while they're working on their assignments. I think I learned a lot from them. Even though I didn't learn a lot from the professors, I did learn from my friends.

What do you think was lacking with regards to the professors?

I mean, there were assignments, and grading, and that was it. There was no back-and-forth, no debates, no arguments, no discussion about art. Also, the curriculum was centred around advertising. I liked thinking of ideas and making ads, but it wasn't my jam. I enjoyed making illustrations and drawing just for the heck of it. I used to like animation as well. But I guess I took what I could from what was offered.

In college, I was introduced to the idea of having a unique style, which is supposedly kind of a big deal in the world of illustration. I also discovered that I was good at copying the styles of different artists that I came across, and for a while I did that. I didn't like the idea of sticking to one style.

Were you ever motivated to discover or create a unique signature style of your own?

I don't even like the term 'style', you know? It's so reductive. It requires you to boil your work down to one way of drawing, and I always wanted to explore different ways of working. I don't think you can or should draw different types of content in the same style. I got to learn more about this when I did my postgrad course at T.A.D. (The Art Department).

Were you keen on studying illustration further after your stint at Sir J J School of Art?

After J J, I wanted to study illustration further, but I didn't quite know where to go. I considered going to the School of Visual Arts, but I was quite broke (laughs). All of these renowned international colleges were completely out of my reach. Around that time, I emailed Sterling Hundley, who is an American conceptual illustrator that I had discovered through Cgunit. I know cold-emailing artists is not always the best idea, but at the time, I was like fuck it, who cares (laughs). I told him about my situation in a long-ass email, and he pointed me towards T.A.D., an online school that he taught at. I wasn't sure how good it would be, since it was an online course, but I enrolled and did the course for two years. But my fears about an online course turned out to be valid as well, because they went bankrupt towards the end — I think they were giving out scholarships to everyone (laughs). I couldn't complete my final year of education with them, which was supposed to be the year that I worked on my portfolio, but the two years that I did spend studying there were amazing. I learnt everything about the fundamentals of art through that course—the teachers were very accommodating.

“I don't even like the term ‘style’, you know? It's so reductive. It requires you to boil your work down to one way of drawing, and I always wanted to explore different ways of working.”

Tell me about your early illustration work.

When I was doing the course at T.A.D., I was also working freelance on a few projects. It was an intense course, so I didn't have time during classes, but American schools have long summer and winter breaks, which was when I could do other work. I was broke the whole time, so I had to keep working. I remember working on a story with Shilpa Ranade, a professor at I.D.C. [the Industrial Design Centre at the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai], who was also an illustrator and animator. She did a lot of tours around Maharashtra and collected stories from the people she met. The story I got was about this kid—there was a lot of famine and drought in the region, and the elder brother in the family had to be taken away to a remand home. It was a very sad story. Nisha (my wife) was freelancing at the time as well—she used to like to write, so wrote the story for me and I illustrated it.

Was it published? What was it called?

I called it Prakash's Story when I put it up on my portfolio, but I don't know if that's the name Shilpa used. I think it was published, but I'm not sure. I did a couple of other small jobs around the time as well, but after the postgrad course, I started freelancing full-time.

Were you very conscious about the projects that you wanted to take on?

Initially, I used to take on whatever I could get. After a while I think I made the conscious decision of only taking on work that would look good in my portfolio—I tried to ensure that the content was good, it was interesting, and of course, that it paid (laughs).

In the past couple of years, you've worked on a lot of comic book projects. What led you towards that medium?

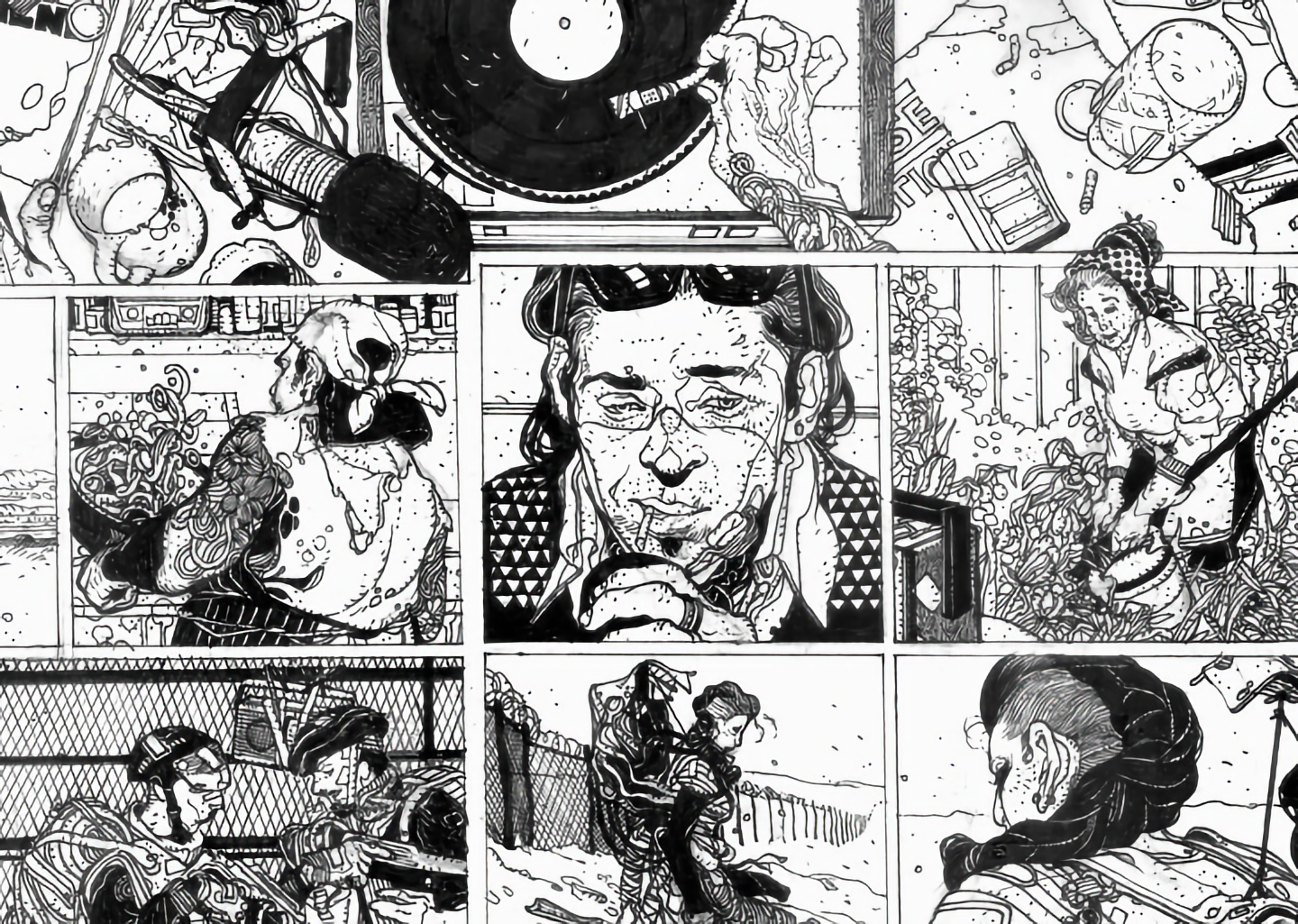

I think for a long time I was torn between pure illustration—illustration for the sake of illustration, not necessarily to tell a story—and comics. There was a phase where I drifted away from storytelling, even though I enjoyed it. I realised that I prefer to tell a story through a single image rather than a sequence of images. Even now, I don't think of myself as a comic book artist. I don't even read comics that much—I should (laughs), but I haven't read a comic book in years. Maybe I'm just lazy (laughs).

A few years ago, I'd gone to Delhi and I met a bunch of guys from a comic artists group called the Delhi Comics Kala Samagam (D.C.K.S.). They were working on a chain-comic project via their Facebook page, and I decided to be a part of that. Bhanu Pratap, Somnath Pal, and a bunch of others were a part of it as well. I worked on a page, which Ram [Venkatesan; writer and collaborator] saw. At the time he was working on the Black Mumba graphic novel, and he asked me to work on the cover. I was always up for book covers.

Was that the first time you spoke to Ram?

Yeah, he wrote to me. And he was great to work with: he paid me an advance, and he paid me well and on time, and I'd never seen that happen. I was like, whoa, publishing works like this? (laughs) It was a very cool experience, and we worked on a couple of other projects together. We worked on a six-page comic called Miracle Men, which was based on a sci-fi story that he'd written. I hand-painted the whole comic.

There's another project called Radio Apocalypse that we're doing together. It's about this radio jockey in the middle of an apocalypse at the only working radio station, which also doubles as a sort of shelter. There's also a weird alien-mutant creature that's running amok at night. It's a pretty interesting concept: we were going to pitch it, but other projects kind of got in the way, and we also started working on Grafity's Wall.

Tell me more about how you started working on Grafity's Wall.

I think Ram went for this talk by a graffiti artist or muralist, which he got inspired by. He also had this idea brewing in his head about doing a story based in Bombay. In a completely different conversation, I spoke to him about creating art inspired by Bombay: it's my city, it's a city that I know already. I was also really excited by the idea of street art, and we decided to combine our ideas.

What was it like working with Irma Kniivila and Jason Wordie (colourists) on the book?

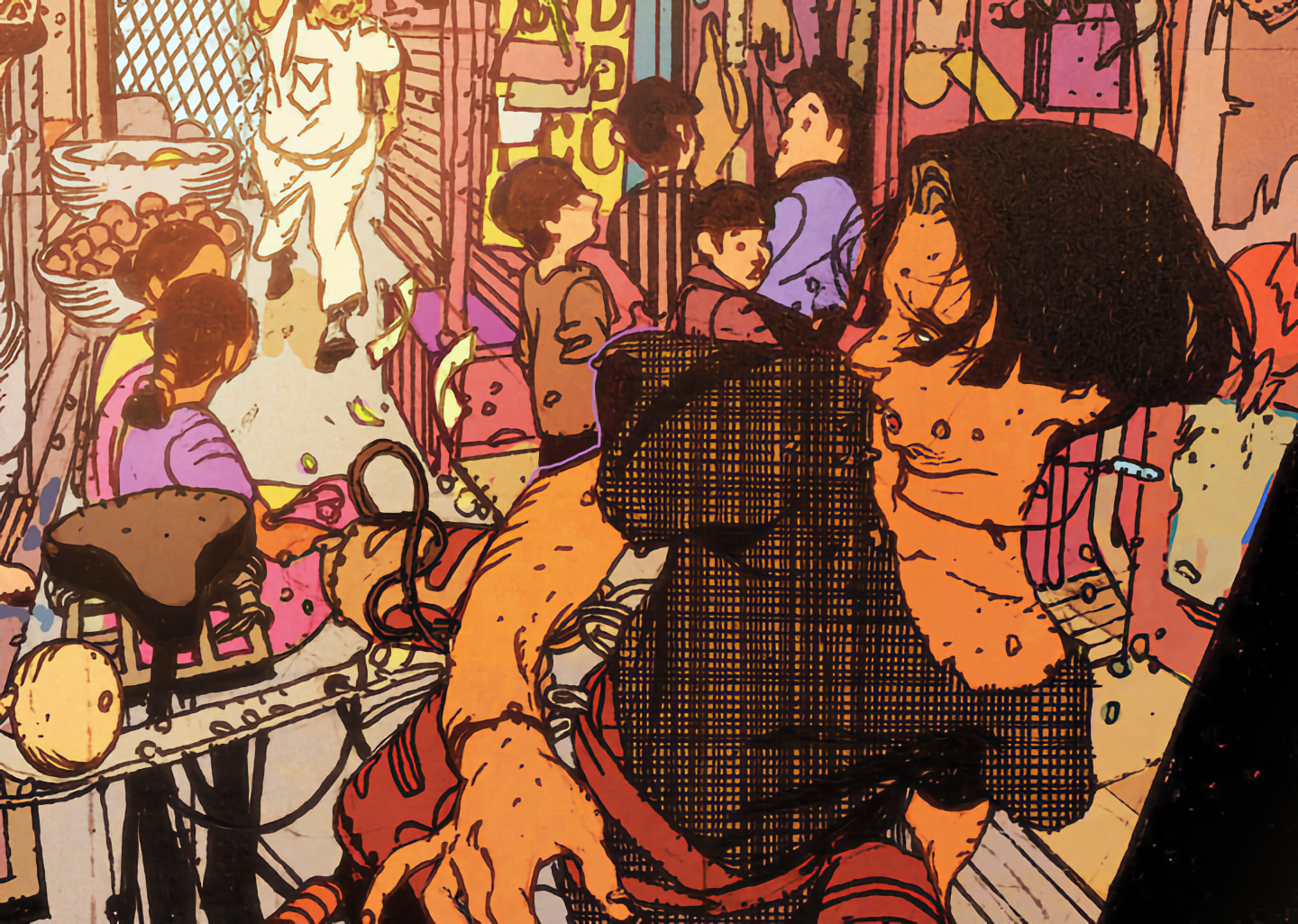

Irma worked on the book in the beginning, but by the 12th page, she dropped out and Jason took over. It took Jason some time to get the tone of the book. Out of all of us, he's the only one who doesn't know the city, how it looks and feels. Also, he wasn't used to doing flat colouring. I had a very specific thing in mind for the colours in the book—I would have done it myself, but there were time constraints. He ended up doing a really good job, though.

How did your knowledge of Bombay inform the way in which you approached the art in Grafity's Wall?

When I say I know the city, I'm sure I don't know it as well as many other people who live here (laughs). When I usually start working on a project, I have nothing in mind; it's a complete blank slate in my head. I find that it's the best way to approach any project, because then it's completely fresh. This ties in to the style question as well. While working on Radio Apocalypse, I was doing this kind of realistic, detailed thing with thin lines—lots of visual information—but at the same time, the lines were all very contrived and straight and angular, because it was that kind of story. I like to do these things with the art, where it sort of bounces off the story.

When I read the first few pages of Grafity's Wall, I realised it was a very different kind of story. It was lighthearted, it was a little bit slapstick, it would remind you of Bollywood and other aspects of the city, and also of childhood, since there are kids at the centre of the story. There are implications and undertones to the story, but at the end of the day it's a slice-of-life story that's not supposed to be taken that seriously. I adapted my style—I don't like using the word 'style', actually, I prefer to use 'personal voice'—from Radio Apocalypse to this story in a way that everything was more organic and exaggerated. I generally try to do a different thing with each project I work on—I don't like to repeat myself. There's no point to this, I just get bored of repetition.

How much time did you spend working on the book?

I think it was a year-and-a-half, but most of the work was done in the last three months. I think that's the case with most big projects, right? Towards the deadline, people start to work a lot more (laughs).

Did you face any challenges while working on Grafity's Wall?

I did, because I'm still new to comics. Grafity is only my first full book. I love the idea of it and it's very exciting, but I still don't have all the chops required to make sequential art. Also, I don't read a lot of comics. But I actually like that, because it allows me to take my inspiration from real life rather than from other comic books. I experimented with a few things visually, drawing from my advertising and design background. My biggest challenge was time management, because I'm not someone who works fast (smiles). I've gotten better at managing my time now, but I'm generally a slow worker. Mostly because I can't just jump into something and finish it. I'll do my research, read about it, try to understand what the characters are like, the work they do, their social circles, etc. With Grafity, when I started, I was doing one or two panels a day, which is terrible. I picked up my pace eventually, and towards the end I had an intern as well, which helped. I've never done this before, so it was all like learning on the job for me.

Do you see yourself as a disciplined person?

I see myself as a hardworking person. I'm extremely persistent, but I don't think I can call myself disciplined. I almost always miss my deadlines, which is a terrible thing to do as a freelancer. It's the worst thing. I've met a lot of other artists whose work isn't very great, to be honest, but they always deliver on time, which is a huge statement. To be able to take myself to the next level I need to fix this aspect of my life.

Do you have any rituals that you like to follow when it comes to your work?

I'm addicted to audiobooks (smiles). The only time I read books these days is when I'm travelling, but when I'm working I always listen to audiobooks, a bunch of fantasy and science-fiction. And I'm a huge tea drinker—I constantly get up from my desk to make tea.

“I'm okay with being an outsider. I love the medium of comics—it has a lot of power when it comes to telling a story. But I would still rather tell a story with one image than with a sequence of images.”

You mentioned that you view yourself as an outsider to comics. Is that something that you want to change?

I don't know, honestly. I'm okay with being an outsider. I love the idea and the medium of comics—it has a lot of power when it comes to telling a story. But I would still rather tell a story with one image than with a sequence of images. I'm doing quite a bit of comic book work now, but I don't consider myself to be a hardcore comic book artist. I think of myself as an illustrator and painter.

Are you working on any personal illustration projects?

Yes. That is something that is a lot more interesting to me. I don't know what they're going to be yet, but I'm working on a couple of world-building projects—building a world and trying to understand how the physics of it works. I'm researching how things move in those worlds, and how I can best put what I have in my head on paper.

Have you considered showcasing your work at galleries and similar spaces?

I would like to, but I don't think I have enough work yet. Right now I'm going with the flow, there's no real plan to this (smiles). But hopefully in the next couple of years, I can look at that. The way I look at my illustration career is as a marathon and not as a sprint. I would rather be at my peak in my 40s, if there even is such a thing as a peak for creative people.

Is it important for you to feel like you're part of a larger community of artists or creative people in the country?

I'm not a very social person, to be honest. I've collaborated with people and collectives before, but I see it as a kind of social experiment. I want to see how I deal with awkward situations; often I get even more awkward than usual (laughs). I am a part of groups, and there is a really great community in India when it comes to animators and illustrators. But at the end of the day, I'm still someone who likes to work alone.

A lot of young illustrators around the country look up to you and follow your work. If you had to give them advice, what is the one thing you would tell them not to do?

I would tell them to not worry about any popular trends or what's cool on the Internet right now. Ignore those things, keep working on your fundamentals, and keep creating original work. I won't say try to find your style, because I don't even know what means, to be honest, though a lot of people say that. Take in a lot of information through different media, but focus on creating original content. I don't see that so much nowadays, especially with the young illustrators on social media. They see something working, and they keep trying to reproduce that, because they keep getting attention that way. A lot of people are also creating work just to please their followers. I don't think that's the way to work.

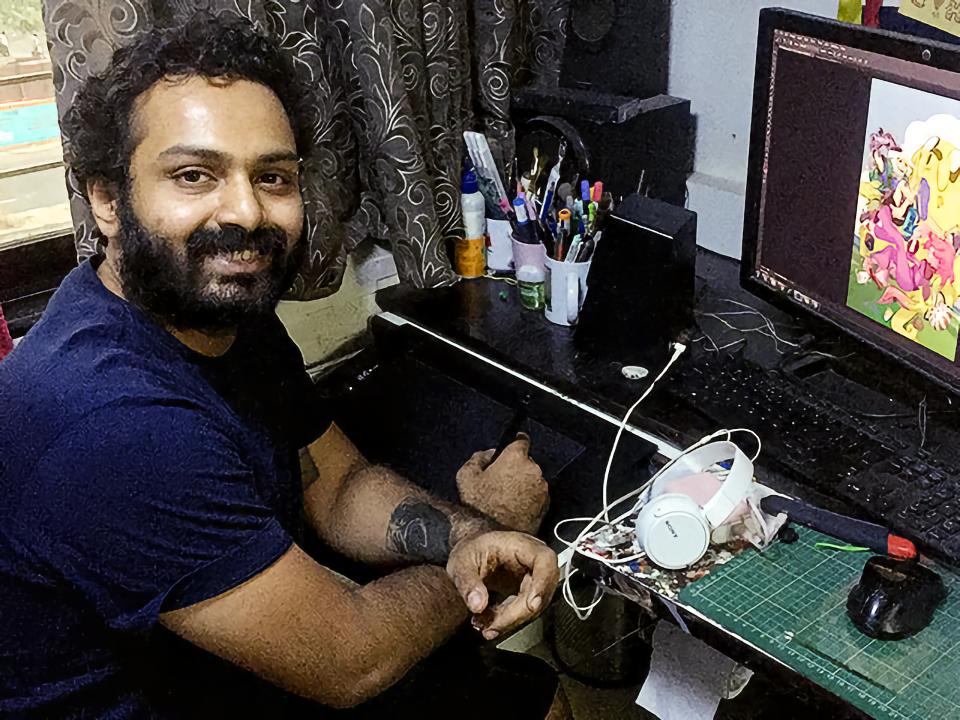

The Setup / Anand Radhakrishnan

"A Mungyo watercolour set, Staedtler EE pencil, Wacom Intuous pen tablet, Canon LiDE flatbed scanner, and Adobe Photoshop CS6. I drew all of Grafity's Wall with cheaply available gel pens, not because they were inexpensive, but because I wasn't getting the right line-thickness with anything else."