"Chennai has a way of protecting you from things, I think," says Shreyas R. Krishnan, a 26-year-old Chennai-born graphic designer and illustrator, who is currently based in Bangalore. "I actually had a culture shock when I went to the National Institute of Design, and an even bigger culture shock when I went to Bangalore after that — never in my life did I ever think that alcohol could be bought in a grocery store."

Shreyas currently works as a designer with Trapeze, a design consultancy in Bangalore, and maintains a visual journal where she obsessively documents her experiences in the form of sketchbooks and other media. Read on for excerpts from a conversation with her about growing up in Chennai, starting N.I.D.'s first student design festival, doodling, transitioning into a coffee person, and her Kaapi and Cigarettes sketchbook swap project —

What was it like growing up in Chennai? Could you tell me about the neighbourhood you grew up in?

I grew up in Chennai and left only after I finished high school. When I was about six, we moved into our present home, which is right next to the Krishnamurti Foundation. There are so many trees around the area I live in; quite lovely for cycling around in the evenings. I come from a Tam-Brahm family, and of course, I'd learnt Carnatic music for four years by the time I was 10. Later, my mother got my younger sister and I to join table tennis coaching at a new club near our house, and I (quite happily, I think) abandoned the music classes in favour of the sport.

Did you enjoy studying Carnatic music at all?

Ha. I definitely appreciate Carnatic music more now than I did when I was learning. While I was learning, though, what was (and still is) fascinating to me was knowing that every composition that I heard or learnt consisted of notes that I could count off my fingers. What was also interesting (and again, something that still interests me) is how the music that my teacher was singing would sort of manifest on her face and in her hands. When you are familiar enough with a certain form of classical music, you know how a singer's hands or head will move when they hit certain notes, or sing certain combinations of notes. Even now when I listen to classical music or music that has classical influences in it, I sometimes find myself unconsciously moving my hands during certain parts of the song.

I wish I had been a bit more serious while I was learning [Carnatic music], but I think my musical abilities and aptitude extended only as far as understanding and singing, but not experimenting and innovating, or getting into it in a more academic way. The other thing was that once you start learning music, at every family function or gathering you're expected to sing, and I never enjoyed that. That possibly stopped me from putting more effort into learning. I started listening to Carnatic music again only after I left Chennai. Perhaps distance made the heart grow fonder? (Laughs) I listen to many types of music now, but some of the music I really love and enjoy is that which has an Indian classical element to it, in some way.

What school did you go to?

I went to Vidya Mandir, Mylapore.

Did you like going there?

School was a fun time (except for Hindi — I could never wrap my head around genders in Hindi). Vidya Mandir was a pretty chilled out place, in some ways. It didn't overly stress on marks, and was quite encouraging of extra-curriculars. There was this thing called 'Project Day', which was two days of show-and-tell, almost. Each standard was given a topic and we'd all spend a few weeks and make models and charts and displays on those topics. I remember the topic when I was in fifth standard was 'Hues, Shades, Tints, and Tones'. Pretty impressive, considering these are terms I only heard again in my first year at design school. I was also part of the Nature Club at school, and we went on a couple of great treks — one was to Silent Valley National Park. My first time to the Himalayas was also on a school trek. From middle school onwards I was pretty much juggling school, table tennis, and tuitions. Standard nerd, perhaps.

Do you think education systems that don't stress on marks and grades are better than those that do?

Oh, definitely, though I'll admit it took me a while to stop tying marks to intelligence. In comparison with a lot of other schools, there was definitely less stress [in my school] on being a centum-scoring golden child. (My dad had a theory that eating bhindi would get me a centum in math. I'm still not sure if he was trying to trick me into eating bhindi.) What was probably given importance was achievements — in sports, academics, music, anything. But even a system as flexible as that falters by the time you hit ninth standard and the Board Exams are all anyone can ever talk to you about for the next four years. Even if a school spends eight years of your life allowing you to do many things, in the last four years you're told that your future is all about the marks — sort of like being a happy Hobbit in the Shire and then suddenly having to carry the One Ring into Mordor?

(Laughs)

These days, I get to speak with people who are/were involved in teaching, and I find that people are now more clued into the idea that different people think differently, and are tailoring ways of teaching and learning accordingly.

Could you tell me about certain incidents from your childhood that may have played a hand in shaping you as an artist?

My mother used to draw, when I was young. She used to make Tanjore paintings, and the whole process for that was so elaborate. It was fascinating watching a board of wood transform into a painting with three-dimensional elements to it. Growing up, my parents bought me a lot of books. I had Little Golden Books, the entire Childcraft series, every Amar Chitra Katha possible, a lot of beautifully illustrated fairy tales. As I grew up, I moved on to more serious books: Mahabharata and Ramayana went from Amar Chitra Katha to Kamala Subramaniam. I learnt how there are multiple tellings of the same two stories, and sometimes stories are made up of multiple narratives. There was one T.V. show that I used to loved watching, a Tamil mystery series called Marma Desam ('Mysterious Land'). I fell in love with how the whole narrative worked, moving across time effortlessly. Between the multiple versions of the epics and Marma Desam, I was understanding the ideas of narrative and storytelling.

I did draw, as a child, but I really started having fun with drawing when we started studying Biology in school. Again, I suspect the Childcraft books may have had a role to play in putting the idea of beautiful diagrams in my head. But, oh, I used to spend so much time on the diagrams, colouring them and labelling them, when all that was needed was a simple pencil drawing that vaguely resembled what was in the N.C.E.R.T. text book.

It's interesting that the idea of drawing scientific diagrams made sketching fun for you. Do you think it affects the work that you do today?

I don't know if there's a direct link between the diagrams then and my work now — possibly, enjoying the idea of documenting. At that time though, I probably thought I was making pretty picture books out of my class notebooks.

Were your parents supportive of your creative endeavours?

In my family, all my cousins (and there are many) either did engineering or commerce. I was the first one (and only one) to go study design. My mother was the one who told me about the National Institute of Design and pushed me to get off my ass and apply.

I'd say my parents have been more than supportive. They didn't always get what I was doing, but they figured it was serious work and that I was happy doing it. I think parents of kids in design schools have to deal with a weird adolescence reboot all over again — "You don't understand me!" (Laughs)

What was studying at N.I.D. like for you?

It was a whole new world for me, in many ways, with the people, resources, work, and experiences it threw at me. It was also the first time I was living away from home for a long period of time; and the first time I was in a place where I was often lost because I didn't know Hindi; the first time I saw people of my age drink and smoke. I still think I wasted my first year there being overwhelmed by everything and got my act together only by my second year. At N.I.D., you needed to be as invested in your own education as the system — maybe more than the system sometimes. You are opened up to certain things, and how much you want to get involved and how far you take things is up to you. You have to make use of the fact that there is a wealth of resources available in the form of books, papers, and people. Once I received the right kind of encouragement from the right people, it was easier to find my footing.

Eventually, I was a part of the N.I.D. Film Club which introduces the community to films in an academic context. I loved being in Film Club and researching and planning monthly schedules. We realised that a lot of times, people didn't really know enough about why a film was important enough for them to make the effort to get to the auditorium to watch it. So, being the graphic designer, I began making small A4-size 'handouts', which were little photocopied fold-downs that gave a quick overview on the relevance of the film, and had a little something about the director. I enjoyed making them, because yay, research! (Smiles) I loved reading up and collating all that content and then figuring out what to put in before laying it out. Once we saw someone's softboard in the hostel covered with handouts they had collected over weeks (smiles). I knew at this point that I am someone who doesn't simply design for content that is given to her — I need to be a part of the shaping of that content as well.

I was also part of a group that organised rgb, N.I.D.'s first student design festival, because we felt that at N.I.D. one tends to get sheltered and cut off from other design students. We wanted it to be an event where the institute would open up and let other students in, and we'd get a chance to just hang out and talk and get to know other students of design.

rgb sounds like a great initiative.

It took us three years to make rgb happen and the first one wasn't the best organised event, but it paved the way for the next few rgbs that happened after I left campus, which were simply amazing.

Did you continue studying design after N.I.D.?

In 2008, I had the chance to go to Politecnico di Milano, for a semester-long exchange program. Culture shock number three of life. It was an amazing experience, but it was the first time I was literally on my own (I learnt to cook while I was there). When I landed in Milan, students were protesting, and in some parts rioting, because there were cuts to the education funding from the government. When classes resumed, I joined the Density Design Lab. It was amazing — a semester dedicated to data visualisation. It was a new type of coming together of content and design for me, and it was great. My classes were in Italian, though, it was funny, since I was the only non-Italian-speaking person in my class. My teachers and classmates were a lot of help, translating during and after classes when I needed help. We had semiotics, statistics, and data visualisation. The funniest thing was when I sat through a semiotics class on 'Barriers to Communication', and it was being taught in Italian! (Laughs) The six months I spent abroad got me quite interested in the idea of "culture" and "cultural/national identity".

Do you think semiotics should be taught at all design schools?

YES. I think it's very important. While some people can be inherently sensitive, a lot of times designers need to go through semiotics to be conscious of what kind of work we are putting out. I once met a kid in Chennai during a semester holiday, and he was all "oh, I don't think you need to go to design school to be a designer", and then he showed me some logos he was working on. I mean, it's all well and good to be proficient with software, but design is more than simply making things "look good". Design, at least visual design, makes sense of information, of communication. And semiotics is certainly a part of the sensitivity that is needed.

What about the idea of national/cultural identity interested you in Milan? Have you explored this after coming back to India as well?

Italy is weirdly a lot like India — no one understands the concept of queues, they eat rice, swear, and fight on roads. Government offices are just the same, you get sent from one counter to the next. There are times when you are an outsider, but there are instances when you suddenly feel like an insider. What got me thinking about the idea of identity in and Indian context was when people in Europe would ask me questions about India. Like, they couldn't understand how one country could not speak one language. I'd gone to Milan with another junior from N.I.D. for the semester, and he's from Gujarat. It was beyond the locals' comprehension that the language we used for communicating with each other (Hindi or English) was not the language we would speak in when we called our parents. Strangely, later I met a couple of Cameroonian students, who could speak Italian, English, and French (because that is an official language there). They both were from different villages, so they spoke their own different tongues at home. They totally got what I was talking about.

These are things we take for granted living in India, being insiders. You really start to wonder: what is it that is holding this diverse population together? That is too large a question to answer, of course, and it not something I have an answer to. It did however get me to start considering things as insider-outsider; a person familiar with a culture, as against a person who is not familiar with it.

You've previously told me that despite being from the land of filter coffee, Milan was where you had your first coffee. Did Milan turn you into a coffee person? Have you had south Indian filter coffee since? Which do you prefer?

Oh, yes, definitely a coffee person now! I still stayed away from coffee for a long time in Milan, until once, some post-pasta lunch drowsiness was too much to handle and I succumbed to my friend's "Caffe?" (Laughs) She kept asking me after lunch, every day that we worked together. It's also hard to NOT have coffee in a country that takes its coffee consumption so seriously. Our class went out for lunch once in Milan, and 20 different people ordered 20 different types of coffee. I have had filter coffee after getting back, but I simply prefer my coffee black. That's not really an option I knew existed until I went to Milan. I got myself a moka pot when I got back from there, and now I've appropriated a French press that was sitting unused at my parents' place. That French press has now converted everyone at my current workplace into having one coffee a day. #coffeecrusade (evil laugh).

(Laughs) What were your first few jobs like after returning to India?

I did my diploma project at Trapeze, and I've worked there ever since. Ha. There's always a variety of projects coming in, so even if I'm not involved on a project, there is a lot to see and learn from simply being around. And I have a great rapport with my boss Sarita Sundar (who has also been a mentor over the last few years); she gets that I carry certain ideas into the way I look at storytelling and communication, and that's been a great thing (smiles).

Did you move to Bangalore when you joined Trapeze?

Yes, Bangalore and Trapeze happened together. I spent about 10 months in the city between 2009-2010 during my diploma project, and moved here a couple of months later (September 2010, to be precise) when I officially joined Trapeze.

What do you love and hate most about Bangalore?

I grew up in Chennai, so obviously the thing I love the most about Bangalore is the weather. I love that there's more than one place to get good craft beer at, and there's ALWAYS something happening in the city — gigs, talks, screenings, exhibitions, plays. And the flowering trees! You can tell the time of the year with the colours you see above and on the streets (smiles). What I hate is how ill-equipped the city still is when it rains. Another thing I dislike is not about the city itself, but hearing people who are not from Karnataka complain about how the locals are rude. Barring a few genuine instances of rudeness, it invariably boils down to unconscious language politics.

Tell me more about the work you've been doing at Trapeze.

From my diploma project until now, my work at Trapeze has been print-based. Not that I have anything against screens and interfaces, but I absolutely enjoy the tactility of paper. There have been some smaller print projects along the way — brochures, leaflets, even a couple of wedding invites — but the bulk of my work over the last three years (and also what I've really enjoyed doing) has been designing books. Now when I say designing books, I mean from scratch. Trapeze's design practice goes beyond the confines of a traditional brief — in addition to our role as designers, we engage in extensive research before and during a project, very often directing and curating the content that we work with.

This process extends into book design as well. It typically starts with a brief from the client, which is something like: "I want a book". The actual design work is preceded by (or runs parallel to) a lot of research, to understand the larger pool of information that the content is eventually based on, followed by working with writers and photographers to get the right tone of voice in both text and image. I love working with content itself, and I really believe that understanding what you are designing for is part of the process of design. Given the range of subjects the books cover, there is a great amount of new learning with each project. Some of these books involve illustration or data visualisation too. The first book I worked on with Sarita was a 450-page tome about the 25-year-long journey of an eye health institute and its innovative models of eye health delivery. Once you start work with a book on that scale, you start seeing any book (or print material) as a narrative in both space and time, as opposed to simply the sum of its pages.

Besides working at Trapeze, you maintain a popular blog as well, which features a lot of your sketches and photographs. What drives you to document your experiences and/or the things around you?

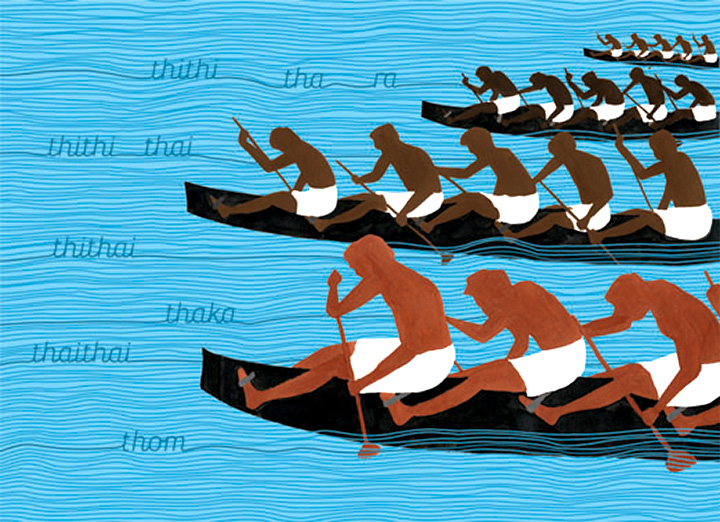

There are two things that I refer to when I explain why drawing is important to me. The first is the Songlines. It is a bit romantic as a notion, and perhaps melodramatic to compare, but it is something I was able to identify with the act of live-drawing. The Indigenous Australians believe that their Ancestors sang their way across the country, and as they sang of everything they saw, the existence of those things was validated; the world came to be. The second thing I refer to is this quote by Milton Glaser, "The great benefit of drawing is that when you look at something you see it for the first time — and you can spend your life without seeing anything." Drawing is my way of experiencing, of being present.

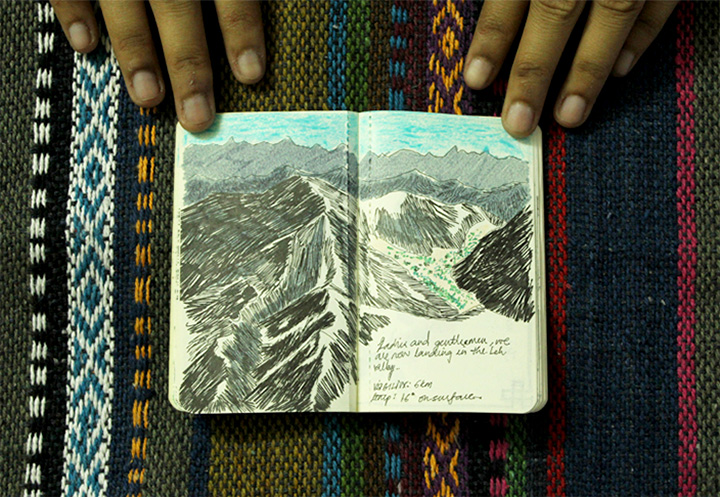

Many times, I write down observations and thoughts along with the drawings, sometimes I simply write. I either stick or pick up ephemera from wherever I am. All of these make up my sketchbooks. Looking back at sketchbooks allows me to trace ideas or remember a thought that I may have had in a place or while drawing — that is not something I can do with the photos that I take. Now that I have a smartphone, I do take pictures, either for reference, or simply if I know that there is no way I'm going to draw something. I recently realised, while going over a sketchbook from 2007-2008, that my first curiosity about the burqa goes back until then. I had completely forgotten about it, and assumed that my interest in the burqa was recent.

While travelling, drawing allows me an easier access to people. There is more curiosity when you sit in the sun and draw a window that catches your fancy, or if you draw a dance performance instead of taking a picture. People are less wary, I guess, and it works as a quick way to gain some trust and friendliness. Unless you're very experienced or good at being inconspicuous with a camera, it can very easily be a wall between you and a subject or a place. Someone may protest having their picture taken; if I'm drawing someone, they invariably end up posing and then come over to have a look and talk with me.

Do you think live-drawing at a concert takes away from actually experiencing the concert in any way? Or is it just your way of experiencing it?

Often, drawing at a concert is my way of experiencing it. I don't draw at all concerts though, only at the ones where I can be visually occupied as well. As I mentioned earlier, part of my fascination with watching musicians is their body language. How their hands move, how their faces change, how their bodies sometimes takes the shape of the sounds they sing. And when I see that, there is again this urge to put pen to paper. What is interesting, is how my drawing also begins to respond to the music I am listening to. My drawings at Carnatic music concerts (or kutcheri, as we call it) are cleaner, while my strokes at jazz shows tend to be a lot wilder. The energy from the music is channeled into the way I draw, and that again is tied to my memory and experience of the music and the concert. There is a lot of stimuli — visual, aural — and I need to let it out and put it in a book to make sense of it. It is also a good way to meet the musicians that I draw (smiles).

Do you sketch daily?

I don't sketch as much these days as I would like to. These days the drawing is usually when I travel, at concerts, putting down specific thoughts and when I am actually illustrating. Eventually work and life get in the way, and you can't spend time drawing every damn thing around you. But whenever I draw, it is because there is an urge to draw.

Could you tell me more about the Kaapi and Cigarettes project that you’re working on with your friend Trusha Sawant? How did the idea arise, and what led to the collaboration?

At one point, the only illustration work that Trusha and I were doing was client work. Kaapi and Cigarettes came out of a need, for both of us, to draw and experiment with media on a more consistent and regular basis; to make drawing and illustrating as regular as the daily kaapi and cigarettes, so to speak. We both have one sketchbook each, and we swap after we have each done a full-spread illustration. A collaboration is always a good way to ensure you keep at something. It also helps when you know, respect, and love your collaborator's work (smiles).

Our subjects are invariably drawn from our everyday — conversations, incidents, absurdities. We try out various techniques and media. The format works well for something like this, because there tends to be less inhibition with working with a sketchbook. Personally, this is also a way of learning for me. Unlike my usual sketchbook-ing which involves drawing directly from life, with Kaapi and Cigarettes I have to push an idea beyond being a drawing and into being an illustration. Trusha and I discuss techniques and subjects whenever we swap, exchanging suggestions and tips, how a certain effect was achieved, etc. It's always exciting at the time of swap to see what Trusha's done.

Recently at a portfolio review event in Mumbai, graphic artist Sameer Kulavoor remarked on the trend of doodling — he said that a lot of young, aspiring artists these days tend to doodle rather than properly draw things, and that he felt that doodling was an alarming trend. He wasn’t a fan of the ‘Doodle Zone’, as he called it. What are your thoughts on the rise of ‘doodling culture’, as is evident on social media?

Hmm. What I would call doodling, is a way of absently drawing. If you are an aspiring artist, then it is key that you are actively present in your work. While doodling itself is not something that may alarm me, glorifying it is. It is important to know the difference between a doodle and a finished, executed piece of work. There are many books on sketchbooks of artists and designers, but they are very clear that the contents of these books are not being passed off as 'work'. You've seen their work, and this is a glimpse into their mind, their process, their distractions. I think the problem is also "meaning". Doodles tend to not really mean much to anyone except the drawer. There's always a grey area between pfaffing and knowing what you're doing, and trying to pass off doodling as 'work' can very easily make you sound very pfaff-y. It's hard to distance yourself from what you are making, and that is something that is critical for creating good work.

The Setup / Shreyas Krishnan

Shreyas' workspace at Trapeze.

Shreyas' workspace at Trapeze.

Shreyas would not like to own a Mac.

Shreyas would not like to own a Mac.

Shreyas' workspace at home.

Shreyas' workspace at home.

Computer + Other Hardware

At work: Apple iMac (21.5"). The screen size is great, and I cannot deny that mouse shortcuts are convenient; but I don't want to actually own a Mac. I also use an Epson Perfection V500 Photo scanner.

At home: Dell XPS, which is quite old now, but works well despite being dropped on the head a few times — you can't expect that from a Mac. I've used it since early 2009. It's due for retirement now. Perhaps another Dell, still debating.

Software

Adobe software — mostly Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign. Projects invariably need a combination of at least two, if not all three. • Gimmebar, to keep track of work that inspires or speaks to me. If I actually find a print of something I like, it gets taped to the wall above my desk. • Evernote to clip articles/text for when I am making notes, and sometime for writing too. Useful for categorising and tagging.

Stationery

A3-size cutting mat that I have had since N.I.D., and a 12-inch steel ruler for cutting • Yellow Lamy for writing and idea thumbnails. Can't bring myself to write with anything else. • Travel/concert drawing stationery usually consists of black gel pens in at least two different thicknesses (Add Gel, Reynolds, anything goes), pigment liners (Staedtler and Sakura Pigma Micron) in different thicknesses, a small box of assorted oil pastel crayons, Sakura Gelly Roll pens, a cutter, a bottle of fevicol or Fevi-stick and maybe a few felt pens... depending on where I am headed. • Poster paints • Gouache paint tubes • Acrylic paint tubes • Too many boxes of oil pastel crayons • Colour pencils (loving the new Koh-i-noor Hardtmuth ones I got recently) • Photo inks • Staedtler colour pens • Staedtler E.E. pencils • Giant dry pastel sticks that I am yet to try out • A few Posca paint markers • Sakura Koi water brush pens (many locked and loaded with different inks) • Reed pens • Lino cutting tools • Ink rollers • Two fat envelopes of collected printed ephemera and assortment of different found papers that get pasted and drawn over or collaged • Various sketchbooks

Was it good for you?

blog comments powered by Disqus